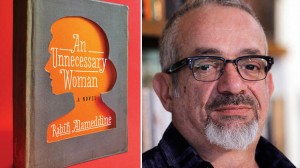

Book Review: Rabih Alameddine’s An Unnecessary Woman

This article is written by Joseph Geha, professor emeritus at Iowa State University and author of two books; Through and Through: Toledo Stories and Lebanese Blonde. In October 2014, the Center invited Geha to lecture entitled “Is there an Us?” centering on immigration, ethnicity and identity. You can view his lecture here.

“I am my family’s appendix, its unnecessary appendage,” says Aaliya Saleh, the eponymous narrator of Rabih Alameddine’s remarkable new novel, An Unnecessary Woman. In her early 70’s, she is a recluse in the same Beirut apartment she has occupied for the last fifty years, a place that reflects her own decrepitude. Alameddine’s 320 page book published in February 2014 by Grove Press is an internationally acclaimed portrait of Aaliya’s mind as it ricochets from ideas of literature and art to the Lebanese Civil War and her own charged past. “A Schoenberg symphony of glockenspiels erupts every time I turn the water knobs,” she wryly observes. “The pipes and I have aged together.” More intriguing than the disrepair, however, is the clutter. Aaliya has a spare room she can barely enter because of the crates of manuscripts she has stacked in it. The manuscripts are works of world literature that she has been translating into Arabic, completing, sealing and storing away for the last fifty years. Although they comprise her entire life’s work, no one has ever read her translations. No one even knows about them. “I create,” she says, “and I crate.” So it seems that Aaliya, this voracious, passionate reader, is also something of a misanthrope. But fortunately, in a novel driven not so much by plot as by the force of her singular voice, Aaliya is a misanthrope whose company doesn’t wear thin.

That’s because, though she may be a shameless literary name dropper, she is also a shrewd observer and, in many ways, a comic genius. In other words, she’s fun to be with. For instance, listen to her explain how she pities James Joyce because

“the only thing some writers ever understand from his masterpiece is epiphany, epiphany and one more blasted epiphany. There should be a new literary resolution: no more epiphanies. Enough.”

Although her personal opinions may be acerbic, her humor biting, she doesn’t seem to care. Aaliya—her name in Arabic means “from on high”—is above all that. Besides, nobody’s listening anyway. As a narrator, isolated and chattering on, she sometimes reminded me of a voice out of Beckett (a comparison I feel she might look on with disdain), a monologist to the void. Alameddine has Aaliya’s narration develop by accumulation in a running commentary of reminiscences, of literary references and observational remarks, many of them engendered by what she is isolating herself from: Beirut, urban warfare, her family, memories of a feckless ex-husband, the loss of her one and only life-friend, Hannah. Sometimes Aaliya’s most casual observations have a way of suddenly veering into the bluntly astute: for example, in reply to the claim that although Beirutis in their sectarian frenzy killed one another like savages during the Lebanese civil war, she suggests that they ought not be judged too harshly.

“Hundred year wars were fought over whether Jesus was human in divine form or divine in human form. Belief is murderous.”

Horrors are effectively rendered as understatement, as in Aaliya’s passing reference to the bombed out Beirut racetrack and the dozens of horses burned alive. Or in the simple admonition about remembering to take a favorite book along with you before going out of the house because

“(e)very Beiruti of a certain age has learned that on leaving for a walk you should never be too sure of returning home, not only because something might happen to you personally, but also because your home might cease to exist.”

Aaliya’s humor—and there is plenty of it—can be witty, haughty, self deprecating (“Mine is a face that would have trouble launching a canoe.”) or even campy, as when she calls Beirut

“the Elizabeth Taylor of cities: insane, beautiful, tacky, falling apart, aging, and forever drama laden.” Nor is she above the occasional pun, referring to Beirut’s recurring electrical blackouts as “darkness risible.”

Still, there is an underlying tension in Aaliya. At one point she interrupts herself with a sudden urgent thought italicized like a hissed whisper: “You must change your life.” And thus it is suggested that this narrator who is nothing if not paradoxical—a translator who translates for nobody, a rejecter of epiphanies—might just be heading smack dab into her own epiphany. Early on she had claimed to want “no more epiphanies” because she feared a false sense of enlightenment. Even so, enlightenment is where Alameddine ends up taking us. The word epiphany comes from the Greek, meaning “the visitation of a god.” In modern lingo, grace. Grace is the chance for change, for redemption. A gift that can befall us in the most mundane of circumstances, at the drop of a hat, say, or when those ancient glockenspiel water pipes finally give way. Rabih Alameddine is the author of the novels Koolaids, and I, the Divine, The Hakawati, the story collection, and The Perv. He divides his time between San Francisco and Beirut. For his most recent work An Unnecessary Woman, Alameddine was a 2014 National Book Award Finalist in Fiction. You can also listen to Alameddine’s February 2014 appearance on NPR’s All Things Considered.

- Categories: