Lebanese Men, Lebanese Women… Is there a difference in how they identify themselves?

This post is written by Amanda Eads, a Sociolinguistics student at NC State University. It is the final installment in a 3-part series that describes the survey she conducted and her analysis that centers on language, identity, and Lebanese heritage.

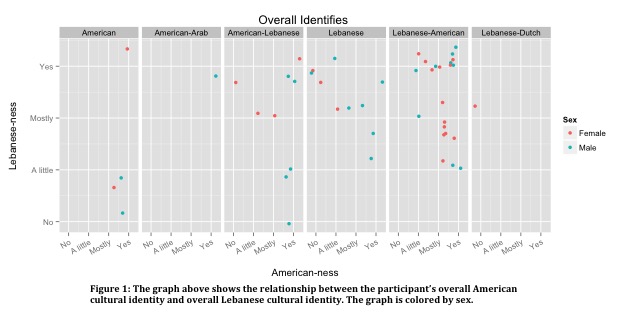

In Part I and Part II of this series, I have discussed statistical results of a survey of 47 participants’ overall cultural identity and language practices. However, with this final post I would like to break down my findings by gender and age. It is important to note that I did not find significant statistical relationships with gender and sex, but this is likely due to the small number of participants. This study used 47 participants, but when I divided by gender, the sample size became much smaller (24 males and 23 females). Still, we can learn from these findings. The graph below is categorized by the participants’ self-identified nationality and reveals the participants’ overall identification with both Lebanese and American culture. It is evident that those who identify as male maintain strong American identity. Both male and female Lebanese-Americans exhibit strong Lebanese and American identity. But, it is difficult to find a trend in the remainder of the chart without further exploring the effects of age and social factors such as immigrant generation, education, and language.

The number of participants in this study was relatively proportional in terms of sex and age however when exploring differences in social factors it becomes clear there are a few instances where sex and age may have influence. There were a total of 47 participants consisting of 24 males and 23 females.

- 4 males and 3 females born between 1930-1950

- 17 males and 16 females born between 1951-1985

- 3 males and 4 females born between 1985-2000

On the surface, education appears to be proportional as well. An overwhelming majority of the participants (20 males and 20 females) report having obtained higher education degrees, albeit there is a clear difference between the levels of degrees. Overall the men have obtained the most education reporting 1 doctoral degree, 11 Masters degrees and 8 Bachelors degrees. The women reported 3 doctoral degrees, 5 Masters degrees and 12 Bachelors degrees. Although the majority of the men report a Masters degree or higher, the women lead 3-1 in terms of doctoral degrees. Taken together, there is not much difference between men and women with Masters and Doctorate degrees. Age doesn’t seem to be a determining factor although it is difficult to say with the small number of participants born before 1951 or after 1985.

Nationality is where differences between sexes become slightly clearer. Men identify as Lebanese twice as often as women, and more women identify as Lebanese-American. Is this because the women identify as more American? Referring to Figure 1 above, I don’t think this is the case as overall women identify as less American than men. While this is an initial analysis, I believe that generational difference may help explain the participants’ nationality choices as the majority of males (18 of 24) are first generation migrants while the females are more evenly split between first (14 of 23) and second (8 of 23) generation migrants.

Generational difference also likely explains the divergence in Lebanese Arabic skills. In Part II of my series, I discussed the link between strong Lebanese identity and fluency in Lebanese Arabic. When comparing proficiency in Lebanese Arabic between the sexes, I found that overall women report higher ability to speak Arabic although more men report fluency. This means that men report either fluency or inability to speak Arabic, while women are more likely to report speaking at various levels of fluency. Additionally, when asked how they feel while speaking Lebanese Arabic and English, women are more likely to report negative sentiments like frustration while men are more likely to express pride.

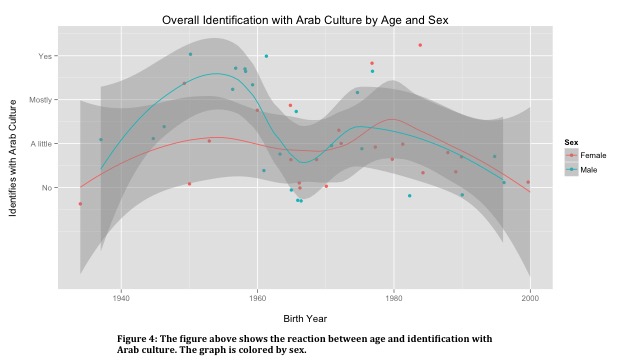

Age becomes a clear factor when looking at language. Men born between 1930-1950 report that they speak no Arabic or have negative feelings speaking Arabic but express great pride in their English speaking abilities. Both male and female participants born between 1985-2000 report pride in their Arabic speaking abilities. However, the males report pride in their English abilities, while the females report that speaking English feels natural. There is a very small number of third and fourth generation migrants in my study, so it is difficult to draw conclusions on language shift from Arabic to English. It is noteworthy that the Arabic reportedly maintained in later generations is specific to prayer, cursing, or food. Below Figures 2, 3, and 4 reveal the participants’ overall identity with Lebanese, American, and Arab culture. The graphs show the participants’ birth year and sex. The graphs reveal that gender plays an important role in the relationship between overall cultural identity and age. Figure 2 shows that women identify more with Lebanese culture than men. Figure 3 and figure 4 reveal that men identify more strongly with American and Arab culture. Figure 2 and Figure 4 show a dip in Lebanese and Arab cultural identification for males born near 1965.

Despite the reported variability in cultural identities, all participants are highly active in the Lebanese community and relatively active in the Arab community. All female and 16 (of 24) male participants reported involvement in a Lebanese organization. However, only 16 of the total 47 participants reported involvement in an Arab organization. While the number of participants is comparatively low, the only group not represented in involvement are the males born between 1930-1950 who are either first generation migrants or are descendants of the first wave of immigrants (1890-1920) and were born and raised in the US. When further exploring the participants’ overall cultural identities and organization involvement, I found a correlation between a strong American identity and not participating in an Arab organization. There was also a correlation with involvement in Lebanese and Arab organizations for the purposes of speaking Arabic. In Part II of my series, I discussed a strong American identity correlating with the inability to speak Arabic. Therefore, it seems that the participants who speak Arabic use these community organizations as a means to maintain their native or heritage language. Psychologist Rebecca Barnes claims,

“Who we are is inextricably linked to where we are, have been, and are going.”

For the Lebanese participants in this study, it is apparent that where they and their ancestors have been is inextricably linked to who they are now in the United States. For some, this link is established through nationality. For others through language and even some through participation in Lebanese and Arab organizations that further their cultural heritage.

References

Barnes, R. (2000). Losing Ground: Locational Formulations in Argumentation over New Travellers. Unpublished PhD thesis. England: University of Plymouth.

- Categories: