When to Stop Archiving

This post is written by Renée Michelle Ragin, a PhD student in Literature at Duke University where her research focuses on the negotiation of national identity in post-conflict Middle Eastern and Latin American states.

Wrestling with intergenerational memory in the wake of political violence is a challenge for many countries. For post-civil war Lebanon, many contend that the work of excavating memory was a project neglected by the state and implicitly relegated to civil society. For a time, it was the project of liberal and elite artists, intellectuals and authors whose work was highly praised. Now, however, especially alongside new and continuously exigent geopolitical developments, Lebanon’s civil war joins the ranks of conflicts that seem to belong to another generation. A new generation of artists born at the end of the war or just after look to the present or ahead to the future rather than backwards at the past.

Must we altogether dispense with the earlier generation’s work on the war? Is it truly no longer as relevant?

The work of at least one Lebanese artist in particular, Walid Raad, serves as a happy middle-ground, straddling an older generation’s desire to remember and a new generation’s drive to buck convention and create futurity.

Some of Raad’s projects, running the gamut from performance art to installations, might be considered anti-memory projects: they argue that how we remember is more meaningful than what we remember, and reject the institutionalization of memory through archival projects, including that of the museum.

Raad’s theatrical and performative refusal of the archive is located metacritically in a critique of institutions and their modes of knowledge production. This style of production serves well as aesthetic analogy for a country with a sociopolitics as complex as Lebanon.

For instance, Raad’s The Atlas Group is a metonym for both a fictional art collective that fronted for the art projects t(he)y produced on the Lebanese civil war (1975-1990) and for Raad, the actual producer. Raad often manipulated the works on display as partially or entirely fictive claims to historical evidence of the war. Distracted by the legitimating power of the archival institution of the museums that housed them, audiences often interpreted the works of art and the information in them as factual and authentic.

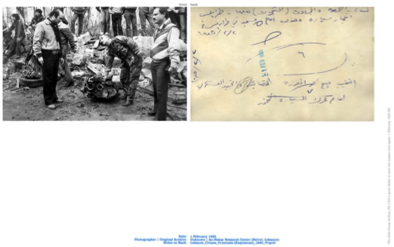

Consider The Thin Neck Files. This dossier purports to depict scenes from the car bombings that so frequently rocked Beirut during the civil war. In one such work, bodies of Lebanese civil war-era car bombing victims are featured alongside a photograph of the handwritten notes on its reverse.[1] Raad collages these images together in a way that draws attention to a large white space that comprises half of the framed image itself. The blank space is relieved only by miniscule lettering in blue: the date of the bombing and the names the archive to which the photograph supposedly belongs. The blue text thus comprises the true physical and abstract framing of the image, rendering visible an archival praxis that relegates the significance of a document or image to its form instead of its content.

In another exhibition, Raad constructed a wall on which he superimposes the image of two other walls facing each other. This larger wall bears relation to, but is not itself the original object. The walls to which this project refers are part of an exhibition entitled Love Is Blind, by Walid Sadek, an internationally renowned Lebanese artist known for his work on trauma and the Lebanese civil war. Sadek’s original walls featured mounted placards that described paintings by Lebanese painter Moustafa Farroukh – paintings that did not themselves appear. Sadek imagines the missing painting to represent not lack, but excess: Beirut’s cultural elite – the keepers of the civil war archive – stood so close to the war that the narratives they produced obscured all else. His artistic imagining thus repeated a rendering of a proximity that obscures all else.[2]

Raad repurposes the walls in his exhibit – mounting an image of the walls on yet another wall. The logic of his reimagined archive is the index of an object which in turn frames the original as a new meta-object.[3]

The power of Raad’s work thus resides in his transparent rendering of a collective desire to grasp any “fact” as “truth” when considering violences that, in actuality, destroy “facts” and records of itself. That audiences flock to museums and art galleries to indiscriminately absorb Raad’s fictive facticity, ironically accounts for its location in these so-called credible sites.

In his satirical displays of the archive’s privileging of form at the expense of content, he reveals a socialized uncritical acceptance of the offerings of corporations, states, and other institutions of legitimation and legitimacy. And it is precisely this obsession with credibility, facticity and history that has the potential to entrap artists in institutionalized logics of “past” and “memory,” precluding creative renderings of the complex realities of life during and after conflict.

Sources

[1] The hand-written note refers to the explosion of a car-bomb in Tripoli, Lebanon on 2 February 1985.

[2] Sadek, Walid and Mayssa Fattouh. “Tranquility Is Made in Pictures.” Fillip 17 (Fall 2012). Accessed 20 October 2015.

[3] Raad, Walid. “On Walid Sadek’s Love Is Blind.” Accessed 20 October 2015.

- Categories: