Meet Elizabeth Saylor, 2016-2017 Khayrallah Center Post-Doctoral Fellow

The Khayrallah Center Post-Doctoral Fellowship in Middle East Diaspora Studies (with preference given to Lebanese Diasporas). This award is open to scholars in the humanities and social sciences whose scholarly work addresses any aspect of Middle East Diasporas. The Center congratulates Elizabeth on her contribution to the field.

What drew you to apply for the Khayrallah Center fellowship?

I was initially drawn to the program by the academic work of the Khayrallah Center’s Director, Professor Akram Fouad Khater. Professor Khater’s book Inventing Home: Emigration, Gender, and the Middle Class in Lebanon, 1870-1920, was a key text that informed my understanding of the life and work of the Lebanese immigrant writer ‘Afīfa Karam and the early Lebanese experience in the United States more generally. As a scholar of mahjar literature, an area that is sometimes overlooked in Arabic literary scholarship, I was very enthusiastic about the possibility of working closely with Dr. Khater and forging new connections with a community of scholars who are equally passionate about the early Arab immigrant experience and its enduring cultural legacy.

You have a strong command of language. Your CV lists 11 languages (excluding English, so that’s 12!) of which you have command. Your undergraduate degree focused on literatures in 4 different languages. Why is this important in your work?

The study of foreign languages has always been one of my life’s greatest passions. In fact, the path my life has taken has been almost entirely determined by my love of languages. For me, language has always been a powerful tool to open doors, bring diverse peoples together, and build stronger human connections. Looking back, I would say that my fascination with languages can be traced to my early childhood. I grew up in a household with parents who were classical musicians in New York City—my mother is a mezzo-soprano and my father an opera composer and professor of music and composition. We lived in Paris and Rome for several years as a family, including two years of kindergarten in French public school. Growing up in a vibrant community of musicians from all over the world gave me exposure to many different languages from a very young age. These early immersion experiences certainly had an impact on my cognitive development, trained my ears, and pointed me in the direction of what would become a lifelong journey.

During high school and college, I began to take up the study a number of languages on my own. I studied Spanish, Japanese, German, Italian, Portuguese, Persian, and Hebrew through a combination of study abroad and formal language study in school. My voracious appetite for new languages would eventually lead me to study Arabic. I was originally drawn to the Arabic language by the sheer beauty of its script. Little did I know, I would become so deeply enamored with this language and its literature that it would become the prime focus of my intellectual and professional life. Today, sharing my love of Arabic with others brings me tremendous joy. Even in courses in Arabic literature in translation, I incorporate mini-lessons on the pronunciation of Arabic, its grammar as a Semitic language, and the differences between classical Arabic, Modern Standard Arabic, and regional dialects of colloquial Arabic. As a teacher of Arabic language and literature in the American academy today, I see myself as a cultural ambassador. I consider it my duty to ensure that, by the end of the semester, my students have achieved not only a solid grounding in the Arabic language, but also a greater awareness of the Arabic language and the myriad socio-cultural, political, religious, racial, and linguistic variations that exist among those who speak it. It is extremely gratifying when my students decide to continue their study of Arabic language and literature, travel abroad to Arabic-speaking countries, and develop their own links to the Middle East and North Africa.

How did you learn about ‘Afīfa Karam and why center your dissertation on her life and work?

I first learned about ‘Afīfa Karam in 2010 while studying for my PhD qualifying examinations. As a graduate student at UC Berkeley, I was deeply interested in the work of the pioneering Arab women novelists. During the nahḍa, or the Arabic literary and cultural renaissance of the late-19th and early 20th centuries, a number of Arab women emerged in intellectual circles as writers, journalists, and translators. Despite the important cultural contributions women made during this pivotal moment of Arabic literary and cultural history, their works remained firmly on the periphery of the Arabic literary field. As a young scholar searching for my own voice, I was motivated and inspired by this brave group of women who dared to enter the male-dominated sphere of Arabic letters and who produced creative literary works at such an early period. Furthermore, I discovered that one of the six pioneering women novelists, ‘Afīfa Karam, had longstanding ties to my hometown, New York City, where all of her literary and journalistic works were published. I felt compelled to learn more about her, but soon discovered that information about her life and work was strikingly absent from both Arabic and English sources. It was this gaping void that inspired me to make ‘Afīfa Karam the focus of my dissertation. Not only is Karam an uncredited originator of the modern Arabic novel, but, as an early voice calling attention to the situation of Arab women, she was also a pivotal figure in the nascent women’s movement in the Arab world. It was clear to me that a serious study of the life and work of ‘Afīfa Karam was long overdue and that – as an early bridge between “Eastern” and “Western” cultures and worldviews – research about Karam’s life and literary legacy was perhaps more urgent now than ever before.

How did New York City impact ‘Afīfa Karam? And in the very early 20th century, what kind of New York City was ‘Afīfa Karam living in?

In 1897, when ‘Afīfa Karam emigrated from ‘Amshīt, Lebanon to the United States, she was a young bride of fourteen. She made the transatlantic journey to the New World, or the mahjar, with her husband John Karam, her widowed mother Frūsīnā, and her younger sister Amīna. The family settled in Shreveport, Louisiana, where ‘Afīfa Karam lived until her death in 1924. Thus, Karam’s primary place of residence was never New York, but a center for steamboat commerce along the Red River in the rural American South. However, Karam would develop very close ties to New York City through her long career as a journalist in the Syrian and Lebanese immigrant press. In the Arab diaspora, just as in Egypt and the Levant, the educational reforms and ideological shifts that took place during the nahḍa created and nourished the burgeoning Arabic press and its ever-expanding reading public. The cultural epicenter of mahjar literary and journalistic activity was located in Lower Manhattan in a neighborhood that would come to be known as “Little Syria.” Between 1892 and 1907, seventeen Arabic daily, weekly, and monthly papers were published in New York City alone. By the age of twenty, Karam had become a frequent contributor to a prominent Arabic daily paper called al-Hudā (Guidance), which was founded in 1898 by a Lebanese Maronite named Na‘ūm Mukarzil. Over the next several years, Karam continued to rise in the ranks of al-Hudā. Not only did Karam direct her own column, in which she discussed women’s issues, but she also served as editor-in-chief of the newspaper for six months while Mukarzil was in Paris attending the First Arab Congress of 1913.

By perusing the pages of al-Hudā, one can garner a wealth of information about the pressing issues and concerns of the Syrian immigrant community in the United States. The newspaper provided the ever-growing Syro-Lebanese population in America with news from Lebanon and Syria, as well as local and international news, and advice to help immigrants navigate the difficult transition to life in America (hence its title, Guidance). At the turn of the twentieth century, the United States witnessed significant technological milestones, such as the first automobiles, airplanes, motion pictures, and long-distance telephone lines. However, the social reality on the ground was far from ideal, particularly for immigrants and other minority groups. All over the United States, and especially in the American South where Karam lived, racial and ethnic discrimination and violence were rampant. These issues, and many others, were hotly debated in the pages of al-Hudā. The status of women was also far from ideal, as women were routinely denied their basic rights, including the right to vote (which they did not gain until the passage of the nineteenth amendment to the United States constitution in 1920). Karam was particularly inspired by women’s rights activism in America and went on to make history when she founded the first Arab women’s journals outside of the Arab world, al-Imrā’a al-Sūriyya (The Syrian Woman) and al-‘Ālam al-Jadīd al-Nisā’ī (The New Women’s World), in 1911 and 1913 respectively. In both her journalism and novel writing, Karam defended women’s rights and criticized oppressive social conventions and patriarchal traditions that she saw as obstacles to women’s advancement. In the end, I believe that Karam’s émigré status and her connection to New York City gave her a unique, hybrid perspective that provided her with a liberating space for artistic creation as well as a powerful voice for justice.

In one of your talks, you explained that there’s some debate among scholars of Arabic literature about the origins and development of the modern Arabic novel. What is the debate and why has it persisted?

The origin and early development of the modern Arabic novel took place during the nahḍa, or the Arabic cultural enlightenment. The appearance and evolution of the novel as a literary genre in Arabic occurred over a significant period of time – roughly between 1850 and 1930 – and involved a multitude of players separated by vast distances. Through the international circulation of the Arabic press, works of modern Arabic prose fiction appeared in places as far-flung as Beirut, Buenos Aires, Cairo, New York, São Paolo, and Tunisia, just to name a few. As a case in point, ‘Afīfa Karam’s three Arabic novels – Badī‘a wa-Fu’ād (Badi‘a and Fu’ad) (1906), Fāṭima al-Badawiyya (Fatima the Bedouin) (1908), and Ghādat ‘Amshīt (The Girl from ‘Amshit) (1910) – were all written in Shreveport, Louisiana, and published in New York. However, despite the importance of Karam’s early Arabic fiction, she is not acknowledged as a pioneer of the form.

I believe that the absence of Karam’s work from the Arabic canon (and the work of other early Arab women writers) demands a critical reconsideration of the dominant narratives of the evolution of the modern Arabic novel. The dominant narratives of the Arabic novel’s emergence often describe it as a road paved by numerous experiments by male writers in Egypt and Greater Syria that eventually culminated with the publication of Zaynab (Zaynab) by the Egyptian author Muḥammad Ḥusayn Haykal in 1914. Despite the enduring impression of this particular literary narrative about the origins of the novel in Arabic (Haykal’s Zaynab is still widely considered as the “first Arabic novel”) the history of the novel’s origin and development is still being written. In recent years, new literary, historical, and cultural research has broadened our understanding of the nahḍa. A study of ‘Afīfa Karam, therefore, joins forces with these scholarly interventions to offer a new perspective that can enrich our understanding of the story of the emergence of the Arabic novel.

By employing Karam as a case study, my research suggests that the rise of the Arabic novel during the nahḍa – and the nahḍa itself – ought to be understood as a transnational or global phenomenon that evolved in fits and starts in various geographically decentralized locations. An examination of Karam’s little known works offers an alternative perspective on the emergence of the Arabic novel during the nahḍa and highlights the vital role played by writers in the Arab diaspora, foregrounding the transnational character of the nahḍa and the mahjar as a locus of literary development that is often overlooked in contemporary studies of the period.

Marginalization is the product of societal power structures. Why do you think ‘Afīfa Karam’s writing has been marginalized?

In my research, I posit that Karam has not been acknowledged as an important contributor to the evolution of modern Arabic fiction because she was a deterritorialized, mahjar woman writer, who composed Arabic novels well before the genre was widely accepted in the Arabic literary world. Due to her triple marginalization within the Arabic literary field – by gender, geography, and genre – Karam’s life and work has fallen through the proverbial disciplinary cracks. A proper examination of Karam’s important body of work, which has never been studied in depth, places her as a pivotal figure in shaping modern Arabic literary and cultural history.

The process of literary canonization is highly subjective, constantly changing, and controlled by elusive and unspoken socio-political, cultural, and literary forces. For example, while a great deal of critical attention has been paid to the literary work of mahjar writers, such as Jibrān Khalīl Jibrān, Amīn al-Rīḥānī, Īlyā Abū Māḍī, and Mīkhā’īl Nu’aymah, Karam has remained largely unknown. Moreover, despite increased interest in the cultural production of Arab-American and Arab-American women writers following September 11, 2001, the overwhelming majority of circulating works are Anglophone works that appeared nearly a century after Karam’s work was published. As the only woman writer to produce a significant body of fiction and journalism in Arabic in the diaspora, or the mahjar, Karam’s output offers a rare window onto Arabic literary culture at the turn of the twentieth century. To put it simply, ‘Afīfa Karam is the founder of a tradition of Arab American women’s writing whose works emerged well before the hyphenated identity marker “Arab-American” came to exist! Ultimately, I further suggest that there is freedom in marginalization. Like her gender, Karam’s émigré status gave her a unique perspective and artistic liberty born of the freedom that distance from the cultural center provided.

Much of your work centers on translation (‘Afīfa Karam’s works have not been translated from its original Arabic; you have worked as a translator; and I’m sure you relied on translated materials in your research). Is translation political?

Issues of translation reside at the core of my work in my capacities as both a researcher and an educator. It can be argued that the act of translation is – by its very nature – a political undertaking. However, when considering the translation of Arabic, the political ramifications are even more acute. Over the past fifteen years, alongside political and social developments in the Arab world and mounting tensions between the Arab world and the west, the Arabic language has gained prominence in western news media and entertainment outlets. The increased visibility of Arabic has both positive and negative effects. On the one hand, recent political and social upheavals in the Arabic-speaking world have greatly increased the demand for Arabic instruction across US college campuses. The expansion of Arabic language education in the United States and beyond has succeeded in spreading greater awareness and cultural understanding among segments of the population. On the other hand, however, the proliferation of distorted media representations of Arabs and accompanying discourses of Arabic as a language of “terrorism” has increased the stigmatization of the language. News stories of American students being “escorted” off of airplanes for speaking the language have become increasingly common. Such events betray a serious lack of understanding and reveal that we still have a long way to go until the Arabic language joins the ranks of languages such as Spanish, French, or German, which enjoy the benefits of neutrality, of being viewed simply as “languages.”

Issues of translation impact my work in other important ways. For instance, I often teach courses in Arabic literature in translation and, in constructing the syllabi for these courses, I am limited to works that are available in English translation. Despite the unquestionable upsurge in Arabic literary translations produced in recent years, the texts currently available to English readers represent only an infinitesimal fraction of the vast literary corpus written in Arabic. Furthermore, the visibility of certain works and the invisibility of others are directly determined by the profit-seeking motivations of the publishing industry. Publishers catering to an English-speaking audience choose to issue translations of works they think will sell. Therefore, they are much more likely to publish works that present heavy-handed social and political messages than more nuanced and creative Arabic literary works.

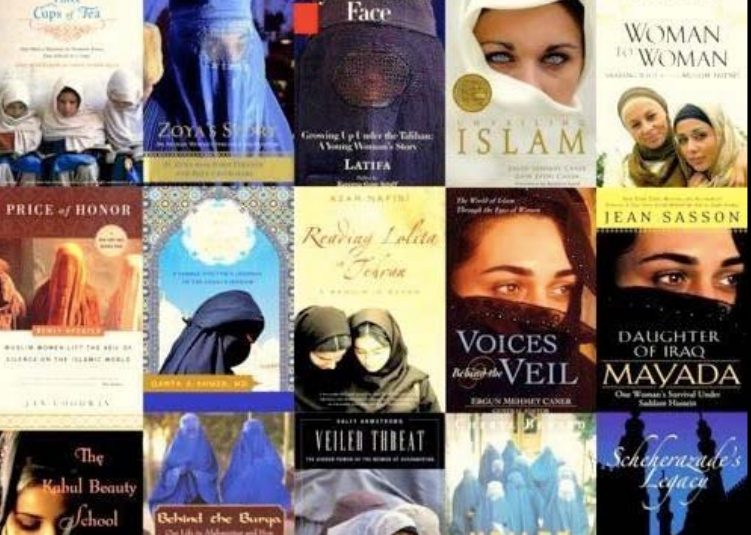

For example, there is a noticeable tendency among western publishers to select Arabic literary works that play into the “oppressed Arab woman” story because this is “what people want to hear.” (see image above right) As a result, some of the most widely read works of Arabic literature in translation (such those by Nawāl el-Sa‘adāwī, for example) portray Arab and Muslim societies as backward, misogynistic, and oppressive. This problematic trend has grave cultural ramifications as it serves to reify an essentialized, limited, and often bigoted view of Arab and Muslim culture and society, while hindering the visibility of more subtle, artistic literary works that reveal more fully the creative potential of Arabic authors. Many writers are working to remedy this imbalance by publishing new Arabic literary translations on literary blogs, websites, and various alternative social media venues. Through their important efforts, new voices are coming forward, such as the Syrian short story writer Rashā ‘Abbās. I strongly believe in the vital role that translators play in making Arabic literature available to a wider audience.

For my own part, I hope to publish my translations of ‘Afīfa Karam’s work in the near future. Karam’s novels and accompanying paratextual writings (introductions and dedications) are vitally important works that shed light on a little known aspect of both Arab and American history and culture. As the only woman writer of the early mahjar, Karam’s work offers a unique vantage point into an important cultural moment. The prescient message of Karam’s life and work – as an early bridge between “Eastern” and “Western” cultures and worldviews – still has much to offer today. Through her connection to New York City’s “Little Syria” – whose traces can still be found on the physical perimeter of the World Trade Center complex – Karam’s story challenges anti-Arab sentiments in the post-9/11 world. The rich history of “Little Syria” demonstrates that “Arabs” form a century-old and important, yet neglected, part of American history. Karam’s fearlessness, dedication to justice and social change, and message of mutual understanding and coexistence continues to inspire me. I am committed to making sure that her story is told, and it is through translation that this can be accomplished.

What is your favorite place to travel?

There are too many places to name! But a few of my all time favorite locations would have to be Palmyra (Tadmur), Syria; the Island of Qarqana, Tabarqa, and Sidi Bou Said in Tunisia; Khan el-Khalili, the Sinai, and the Western Desert in Egypt; Rome; and the San Francisco Bay Area.

- Categories: