Arbeely family: Pioneers to America and founders of the first Arabic language newspaper

This article is written by Dr. Akram Khater, Director of the Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies and Khayrallah Distinguished Professor of Lebanese Diaspora Studies, and Professor of History at NC State. This research would not have been possible without Ms. Martha Hess, Volunteer in the History Room, Maryville College Archives for her help in providing the photo and newspaper clippings. Dr. Khater recently co-authored an article on Michael Shadid: A Syrian Socialist.

In the long and storied history of Lebanese immigration to the United States, the Youssef Arbeely family stands out—doubly—as pioneers.

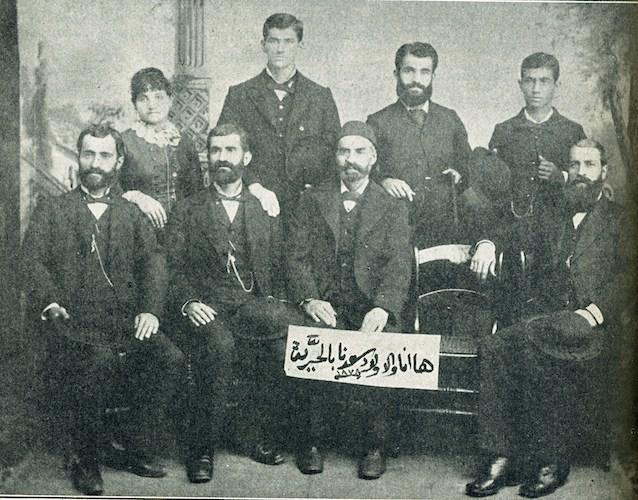

Youssef Arbeely, his wife Mary, six children, and niece were the first family to arrive at the shores of the US in 1878. Eulogizing his father in August 1894, Najib Arbeely explained why “he brought” them to the US: “Because of his love of learning and progress he left the homelands and departed from family and friends and rode the seas casting caution to the wind, and arrived in these lands with his family and children and thus attained the desires of his heart and his purpose [search for knowledge].” The Arbeely’s second distinction is that two of the children, Najib and Ibrahim, established the first Arabic language newspaper in America, Kawkab Amirka, whose inaugural issue appeared on April 15, 1892. (As part of its early Arab-American newspapers preservation project, the Khayrallah Center has digitized Kawkab Amirka and it is available online through our archive). In both instances, the Arbeelys paved the way for subsequent immigrants and planted the seed for creating a community in America.

Youssef Arbeely was born in 1820, some four miles outside Damascus (Syria) in the village of Irbeen. (The family name was originally Irbeeny, and only became anglicized as Arbeely in the US). From an early age he proved to be adept at schooling with a “keen mind and insatiable curiosity.” From a local tutor he quickly moved to more formal education at the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate school in Damascus making the daily roundtrip of eight miles on foot. His sojourn in Damascus allowed him access to a learned circle of Muslim scholars, even if that access at times meant that he stood “behind the closed doors of mosques [he was forbidden to enter]” listening to lectures and lessons. In short time, he went from being a voracious student to the director of the same Greek Orthodox Patriarchal school, and from letters and math to studying medicine with Dr. Mikhail Mishaqa (one of the luminaries of the Nahda, or 19th century Arab literary, cultural and scientific renaissance) and the American missionary Dr. Bolden. In addition, he taught Arabic to a good number of the American missionaries in the Middle East, and helped introduce Sunday school lessons and bible study to the Greek Orthodox church in Damascus.

His ecumenical approach to learning from such a diverse set of religious and secular scholars, only continued after he moved his family to Lebanon in 1860 following the sectarian violence that wracked Damascus that year. For the subsequent eighteen years, Youssef continued his career as a student and educator opening a new school, enrolling in medical courses at the Syrian Protestant College (later to be renamed American University of Beirut), joining the latter’s faculty as professor of Arabic, and then becoming principal of the School of Suq al-Gharb at the invitation of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch Hierothios.

With a life dedicated to acquiring and sharing knowledge, Youssef took the next and last step in his journey: America. Shortly their arrival in 1878—and before the two sons (Najib and Ibrahim) launched Kawkab Amirka in New York—the family crisscrossed the US. Their first sojourn was in Maryville, Tennessee. A small town (with a college by the same name) of 1000 people, Maryville would seem as an unlikely place to become the first home of the first Arab-American family. However, it was the American missionary connection that facilitated this move. In an 1877 letter, Rev. Henry Jessup—one of the founders in 1866 of Syrian Protestant College in Beirut—wrote the president of Maryville College of a “Syrian family of high respectability who wish to emigrate to the United States. I have known the father and the eldest son for many years and feel deep interest in the welfare of the entire family.” With this recommendation, the family made their way to Maryville, arriving there in September 1878, a month after landing in New York. From newspaper accounts, and account books, it appears that the family settled in fairly quickly.

Ibrahim (the oldest son at 28 years of age) began practicing medicine with his father immediately (local newspapers carried admiring reports of him taking out a cancer out of a patient’s eye in the nearby mountains of North Carolina). Khalil (the second at 25 years of age) was a tailor and shoemaker and he started working at a local shoemaking shop before striking out on his own in Little Rock, Arkansas. Fadlallah (who was 23) had also graduated like his father and oldest brother from the Syrian Protestant College as a doctor, and he began practicing medicine around Maryville and surrounding areas. The three youngest boys (Habib, Najib—who was 16 at the time—and Nassim) as well as their young cousin Jumelia enrolled the preparatory school at Maryville College to learn English, among other things. Najib graduated from Maryville in 1884, and during his studies served as French language instructor between 1878 and 1882. Najib integrated quickly into the social fabric joining the Athenian Society debate club and becoming its president by 1882, as well as playing baseball (second baseman for the Blues of Maryville). By 1890 most of the family had relocated to Los Angeles, California where more tragedy befell them as one of the sons, Dr. Fadlallah Arbeely, passed away in 1892 and only two short years later Youssef himself died and was buried next to Fadlallah.

Somewhere between his tenure in Maryville and his father’s death, Najib and his brother Ibrahim had relocated to New York where they worked to set up Kawkab Amirka. At the same time, Najib distinguished himself in a multitude of ways. Seven years prior to establishing the newspaper, U.S. President Cleveland appointed him as Consul General in Jerusalem (Dr. Linda Jacobs has an a forthcoming article on his tenure in Jerusalem), and he was subsequently appointed as Assistant Inspector at Ellis Island where he played a key role in facilitating the immigration of many Lebanese into the US.

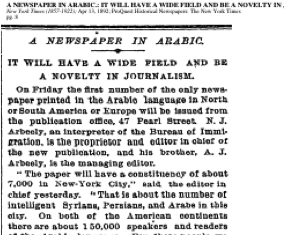

In addition to all of these accomplishments, Najib embarked in 1892—with his brother Ibrahim—on a new venture to establish the first Arabic newspapers in the United States. This was significant in at least two ways. For early Lebanese immigrants living throughout the US (see map of 1900 census to get an idea of the geographical spread) a newspaper was one of the very few means they could have to connect with each other, discuss and argue over common issues, and build a sense of community (harmonious or contentious). In fact, in the opening editorial of Kawkab Amirka, they wrote: “Many know that Ottoman subjects [as he labeled early immigrants] have become an important part of the United States…but they are spread out seeking their livelihood throughout the states…so this newspaper will gather them in a literary manner, and will seek their news…” Moreover, he added: “This newspaper means to link immigrants with their people back home in the East through its news.” As one of the luminaries of early Lebanese immigrants (highly educated, well-traveled and very likely highly regarded by the Lebanese-American community) he was best placed to accomplish this goal.

At another level, this was a momentous project because it introduced Arabic—technologically as typeset, and as “strange” text—into the mainstream of American society. Until Najib and Ibrahim started their newspaper, the Ottoman government had prohibited the export of Arabic typesetting equipment and letters outside the empire. This was driven by fear that political exiles would use the technology to print anti-government tracts especially in European capitals like London and Paris. However, it appears that the Arbeelys were able to overcome this embargo because of their presence in the US (which the Ottomans regarded in the 1880s and 1890s as a friendlier country that had no ambitions—like the French and British—to extend its power over the Middle East), and because they publicly espoused a very loyal position vis a vis the Ottoman Sultan. Thus, in the same opening editorial of 1892, they wrote: “Long Live our Sultan Abdul Hamid.” On the English page of the same inaugural issue (the newspaper which came out weekly on Fridays, published one page in English and the remaining in Arabic), they wrote: “Among all the Sultans who have sat upon the throne of the Ottoman Empire, none has achieved greater success in raising the Ottoman people to a higher position among the nations of the earth, than the present “Great Prince of the Faithful” Abdul Hamid.

Regardless of whether this was a sincere sentiment or a means to an end, the result was the same: Arabic found a home in America. Remarking on this momentous event, publications like The Evening World, New York Herald, and New York Tribune carried reports of the newspaper and its venture as a voice of the community (and later of libel suits against it by unhappy readers!) While the newspaper was short-lived, and within few years other Arabic newspapers appeared and competed with it to be the voice of the community, Kawkab Amirka and the Arbeely family remain pioneers who shaped the lives of many early Lebanese immigrants.

- Categories: