“Like a wolf who fell upon sheep”: Early Lebanese Immigrants and Religion in America

For some early Lebanese immigrants, religion was a source of comfort. Its rituals, language and congregations provided a sense of home in an alien environment, and stability amid the fast-paced changes they experienced in their new lives. For others, it was an oppressive reminder of a past they left behind, and a source of discord and dissonance among coreligionists, as well as between members of one faith and another.

Between 1880 and 1930, thousands of men, women and children departed the Eastern Mediterranean for the Americas. They arrived in new lands [the mahjar] where many people, at best, tolerated them and more frequently maligned them. Their daily encounters, at work and in society at large, necessitated a self-conscious examination and re-creation of their individual and collective identities. This reality—which, for nearly two-thirds of immigrants, also entailed permanent relocation to the US and other countries—and the anxieties it generated propelled many immigrants to try to recreate a community that would anchor them amid all the economic, social and political forces tugging at the fabric of their lives. Family, food, language, social gatherings, clubs, letters home, infrequent return visits, and Arabic-language newspapers were all part of this process. Equally, and at times more importantly, religion was also at the heart of building and maintaining community in America. In this essay we explore these divergent roles that religion played in the lives of early Lebanese immigrants.

Historians have suggested that more than eighty percent of early “Syrian” immigrants to the United States were Christian while the rest were Muslim and Jewish.(1) However, sources for these estimates are unclear as few contemporary documents recorded immigrants’ religion. Christians were divided among Maronite Catholic, Melkite Catholic, Syrian Orthodox, and a small number of Syrian Protestants. Muslims were represented by Sunni, Shi’a, Druze, and a few Alawite. Syrian Jewish immigrants had affiliated with Eastern European Jewish refugees migrating to Syria and Palestine in the late nineteenth century and often settled among other Jewish enclaves in the United States, although they established their own ethnic Syrian Jewish Synagogue in Brooklyn.

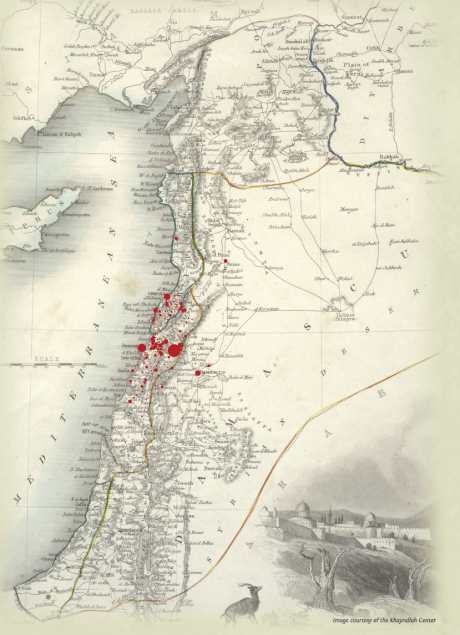

Regardless of religion, upon arrival in the United States, these immigrants spread rapidly throughout the country settling in both urban and rural landscapes, following railroad lines to the Northeast, Midwest, South and West. They pursued jobs in industrial factories, as merchants in booming mill towns, or as peddlers to American farmers in the far reaches of the land. Yet, despite relocating thousands of miles from home and settling among ethnic cohorts, religion remained an important marker of identity among most immigrants. Thus, and especially during the period between the 1890s and 1950s, Syrian immigrants established churches, mosques, synagogues, and religious organizations to promote and maintain their faith and community in the Mahjar. One of the first steps, then, for those who sought refuge and solace in a transplanted religious community was to create one, and the starting point of that effort was to obtain a local priest, rabbi, or shaykh.

In describing their need, they wrote: “As your beatitude knows, we—the Syrian children of your holiness—live in this country among different nations with different religions, some are Catholic but the majority is Protestant. We are in great need for priests to live among us and to perform their religious duties.” In detailing their wants and desires, the writers (who identified themselves as originally from the towns of Bsherri, Beirut, Tarza, and Bayt Meri) noted the difficulty of finding a Catholic priest to serve their spiritual needs, especially for those peddlers “who are always traveling in these lands to sell their wares.” Even when they did encounter one, they remained unable to properly confess “because many of them cannot speak English well.” This sorry state of affairs meant that the great majority of these “Syrian” immigrants went for years without a confession, or fulfilling their religious duties, which led to a “falling away from the faith.” What is worse, from the perspective of the writers anyway, is that some began to attend Protestant churches. In short, they–and others in dozens of similar letters–inform the Patriarch, the community’s spiritual welfare is at a perilous juncture without a Maronite priest.

Melkite Catholics and Syrian Orthodox faced a parallel crises. In the years and sometimes decades before immigrants could secure a priest and establish a church, they found alternative ways to worship. Melkites and Maronites, who were part of the Roman Catholic Church, often received support from established Catholic churches in the United States. These churches provided basements for Syrians to hold services and hosted itinerant Maronite and Melkite clergy. In Utica, New York, St. John’s Roman Catholic Church served the Maronites and Melkites until they were each able to establish their own parishes in 1907 and 1914. In some cases, Syrian Christians shared their churches with compatriots of different sects. In Chicago, the Syrian Melkite community established a church in 1894 and opened its doors to both the smaller Syrian Orthodox and Maronite communities.

Many communities too small or young to erect formal religious institutions established religious clubs to promote meetings or specific functions in absence of religious institutions such as funding cemeteries and giving aid to families in need locally or in the Mashriq. In 1908, the Druze community formed the Al-Bakaurat El-Dirziyet, a fraternal organization with branches in cities around the country to “unite American Druze immigrants and keep them tethered to their faith, culture, and heritage, while also enabling them to assist their people in the homeland.”(2) In Lawrence, Massachusetts, immigrants formed the United Syrian Society in 1907, a multi-religious organization with the purpose of establishing a common burial ground for the Syrian immigrants of the community.

To avoid the peril of spiritual and communal loss, “Syrian” immigrants established 39 Maronite churches, 21 Melkite churches, 58 Orthodox churches, a mosque, and a synagogue across the United States between 1890 and 1924.(3) The majority were located in the Northeast and Midwest, and a couple in the South and West. For many immigrants, these religious institutions became “a powerful social force” in the life of the community. At the most basic level, they provided a fixed space where ceremonies or prayers were officiated and recorded with a permanence that affirmed their religious heritage and identity. The registry of Saint Joseph Maronite church in New York provides one example.

On May 22, 1909, Father Francis Wakim performed the marriage of Tawfiq Tanyous Boutrous al-Hajj and Anisseh As’ad Shakir, with Charbel Kamel and Cecilia Khalifeh as witnesses. In Father Wakim’s notes, he recorded the original places of baptism of bride and groom respectively as “Bikfaya, Lebanon,” and “Bzebdinne, Lebanon.”[i] Thus, and in two lines, distance between America and Lebanon was erased, and two places and lives were merged by a transcendental moment of religious faith and ceremony. The presence of friends and family at these ceremonies only reinforced a sense of community with deep transnational roots. Equally important is the socio-economic role religious institutions played by providing a space where social networks were built and mobilized. The social events they housed and religious services brought members of the community together regularly in a way difficult to replicate or replace with a secular setting, especially outside major ethnic enclaves like New York, Detroit, or Lawrence. Those were moments where information was exchanged about business, potential spouses, and others news of the local community. One second generation immigrant to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania commented on this when he said: “My father goes to church and pays a lot of attention to it. Why not? It’s a real pleasure for him. He meets his friends there and has a good time talking to them.”

Social Discord

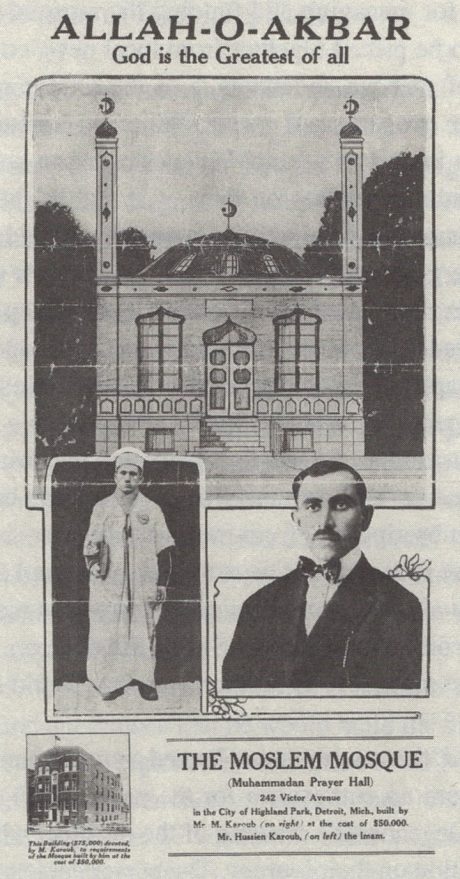

As much as establishing institutions and hosting clergy did provide a touchstone and a measure of moral and social cohesion for immigrants, they were paradoxically also a taxing proposition that at times threatened to tear the community apart. Financially, they demanded a great, and long-term, commitment from a community of immigrants struggling to make ends meet, and not certain of the length of their stay in the Mahjar. In Highland Park, Michigan, a Muslim community flourished alongside Henry Ford’s car factory. In 1919, Sunni immigrant and

entrepreneur, Mohammed Karoub, embarked on a mission to establish the first mosque in America to serve the large Detroit Muslim community of both Sunni and Shi’a. Planning to invest some of his own money, Karoub also traveled with his brother, Imam Hussein Karoub, on a trip around the country selling subscriptions to the mosque as a means of sustained support for its management and upkeep. In the fashion of an itinerant clergyman, Hussein performed marriages and prayed at the graves of the dead, for Muslims who did not normally have access to the services of an imam. The Karoubs visited Arabic-speaking Muslim communities in Connecticut, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, Indiana, Iowa, the Dakotas, and elsewhere. The mosque was completed in 1921, but despite Karoub’s fundraising and publicity efforts, it was abandoned after only a year due to Sunni-Shi’a factions in the community as well as other tensions related to the leadership of the mosque.(4)

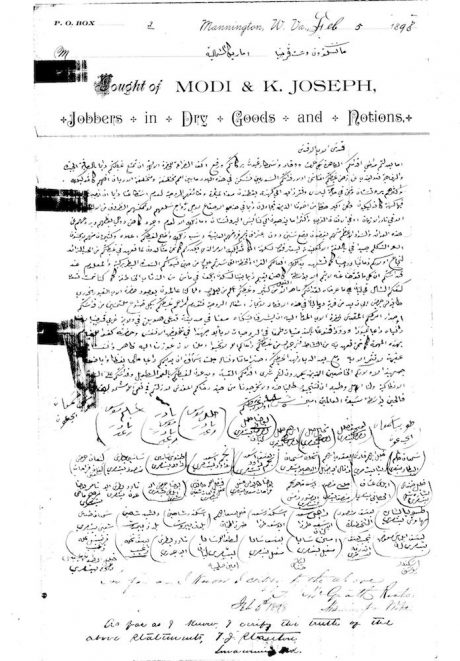

Other communities also grappled with the tensions of building permanent religious establishments. Not only was it necessary to collect thousands of dollars to build or buy the physical building, but many Christian communities also needed to provide housing for a priest and a monthly stipend for his living expenses. In 1906, Maronite priest, Boulos Ibrahim Masrah, from Wheeling, West Virginia, wrote Patriarch Howayek, to let him know that—among other matters—the church in nearby Pittsburgh was recently sold for fifteen thousand dollars, and that the community in Wheeling is paying him a monthly stipend of fifty dollars, in addition to the fifteen dollars he was getting from the local bishop. In New York City the cost of buying property for a church in Manhattan exceeded $35,000 in 1903. Further north, in Buffalo, New York, the process was also proving relatively expensive. Beshara Saffi, a local merchant, wrote in May of 1903 to complain of the extravagance of the local priest, Father Jirjis Aziz al-Jizeeni. Among his many other faults, he bought a residence for himself that cost two thousand dollars, a sum “which he collected from community members, and he still owes $4500…”

Ironically, priests were an even larger source of contention. Some of them behaved badly, others were ill-prepared to serve outside of their familiar environment in Mount Lebanon and Greater Syria, and still others bickered and argued with each other about authority over their followers in America. This conflict-ridden period was reported repeatedly in letters to Maronite Patriarch

Howayek, and published on the pages of immigrant newspapers. On February 24, 1901, some sixty-one members of the Maronite Benevolent Society of St. Louis (Missouri) signed a petition to Patriarch Howayek asking him to “save us from a horrible disaster” that befell them with the arrival of Father Matta al-Ghaziri, previously of Cuba. They accused him of pitting “brother against brother and friend against friend,” which has brought “financial ruin, shame and scorn upon the community.” His purpose in doing so was to gather enough money to build a church to replace the rented space the parish had been using for several years.[vi] Three days later, another group from the community put their signatures to a counter-letter which extolled the virtues of Father al-Ghaziri and accused those opposed to him of being moved by “jealousy and hate.”[vii] In Buffalo, matters got to the point “where the Maronites were fighting in the streets.” What sowed such terrible dissension was Father Jirjis Aziz al-Jizeeni, the parish priest. In a series of thirteen sworn affidavits, members of the community accused him of “laying down with women of ill-repute,” “playing the banjo, singing vulgar songs in the Syrian language, and dancing the Hoochi Coochie,” and playing cards and “shaking dice” in a saloon.[viii] In 1902, members of the Maronite community in Boston wrote the patriarch complaining about all the missionaries, who: “neither their conscience, nor laws keep them from seeking money honestly or otherwise…who refuse to fulfill their religious duties, hearing confession, and officiating at marriages and funerals before they get paid. Many times they have even sold Syrian children to American women, and made agreements with Americans not to hire Syrians in factories unless they get a kickback.”[ix] Of course we cannot be sure of the truthfulness of such claims, and even if true they certainly did not apply to all Maronite clergy in the US. Nor can we be certain of how widespread these complaints were. But regardless of these caveats, the petitions and letters stand as testament to a tarnished reputation and periods of antagonistic relations between some missionaries and some members of the community.

Disputes among Maronite clerics only exacerbated these communal fissures. Perhaps the most consequential—judging by the number and tenor of letters generated around them—was the long-winded and geographically expansive argument between Chorbishop Youssef Korkemaz Yazbek and Chorbishop Istifan Khayrallah. Coming from Lebanon to the US at different times, Yazbek in 1890 and Khayrallah in 1900, the two chorbishops [this is a clerical rank between priest and bishop] clashed quickly and loudly, with factions readily forming around them, over who was to be the Superior of the Maronite missions to the US. Personal ambitions and theological quibbling led to strong words splashed across the pages of newspapers, and countering petitions asking the Patriarch to intervene. Long before the arrival of Khayrallah, Chorbishop Youssef Yazbek—an indefatigable traveler across the eastern half of the US, and an intrepid self-promoter—had been proclaiming himself in the American press as the Maronite Superior. Upon his arrival, Chorbishop Khayrallah quickly challenged this status quo. On May 2, 1900, shortly after landing in New York City, he wrote Patriarch Howayek: “Chaos reigns supreme, and the [Maronite] missionaries’ only concern is to sow the seeds of contention…and pursue that which benefits them personally.” His proposed solution was for the Patriarch to unify the authority in a single person over all missionaries. As the matters escalated between these two Maronite clerics in America, and complaints poured into Bkekri, Howayek lost his patience. In 1902 he wrote to Chorbishop Khayrallah Istifan in New York: “In truth, we are unhappy with you and them [Yazbek and other priests] because rather than being missionaries working to save souls and providing a good example you have abandoned all virtue and zeal and lost the pure spirit of the Gospel… [You have become] a stumbling block for those poor souls who were already struggling with loneliness and distance from their beloved country and family, and now because of you they are also distant from the principles of religion and the spirit of Jesus Christ.” In the end, neither was allowed to claim the title of leader of the Maronite mission in the USA.

The Syrian Orthodox community faced an almost identical conflict in the 1910s, which split the American church and its parishes in two. In 1914, the patriarch of the Syrian Orthodox community in America, Bishop Raphael Hawaweeny, died opening the doors for debate over who would succeed him. Hawaweeny had been an affiliate of the Russian Orthodox Church in Moscow, but before that church could name his successor, it was wracked by conflict with the onset of the Russian Revolution in 1917. Meanwhile, in the United States, Bishop Germanos Shahadi, an affiliate of the Orthodox Church of Antioch, laid claim to Hawaweeny’s legacy in America. Bishop Germanos was well liked and respected by many priests and communities in the U.S. However, when the Russian Church finally appointed Bishop Aftimios Ofiesh as Bishop Hawaweeny’s successor, the Orthodox community became divided over those loyal to the official decision of the Russian Church and those loyal to Bishop Germanos Shehadi.

Throughout the country, and for over a decade, orthodox communities divided their loyalties, severing parishes in two in what became known as the Russy-Antaky split. In 1925, members of St. George Church in Allentown, Pennsylvania battled over property rights to their building on Catasauqua Avenue. Those loyal to the Russian church selected Fr. Sophronius Beshara as their pastor while the Antiochian cohorts chose Fr. John Saba. Even still, the two groups entered a bitter dispute over who had the right to worship in the building they had constructed in 1917. The argument was finally resolved in court nine months later when a judge ruled in favor of the Russian faction under the leadership of Bishop Ofiesh.(5) The Antiochian priest, Fr. Saba, was forbade from holding services in the church but ministered to the Antiochian followers in local homes for a few years. Ultimately, the American Syrian Orthodox church resolved their conflict in the 1930s under the leadership of Antioch, and many, but not all, severed parishes reunited.

Critiques

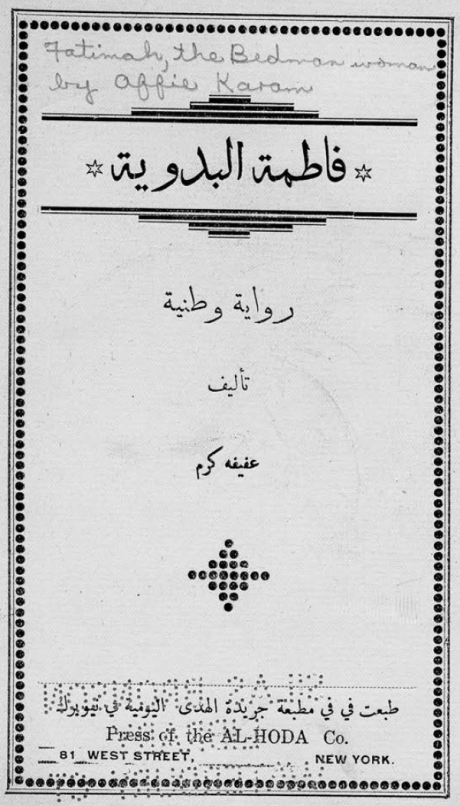

These episodes and others like them, provided evidence for mahjari intellectuals and other immigrants of the “moral bankruptcy” of organized religion, and raised questions about the limits of religious authority over the lives of immigrants. Author Amin Rihani (a contemporary of Jubran Khalil Jubran) articulated these doubts and criticisms in regards to the Maronite Church in his book al-Mkari wal-Kahin.[i] Abou Tannous, the protagonist who had recently returned from “Amirka,” announces at an early point in this encounter: “Ah, our respected father! You live a life based on lies, a life whose rules are malicious, and its outcome is tyranny and oppression of those who are beneath you…You preach contentment whilst you collect in your coffers the monies of the nation…you forbid evil, and yet rarely do you ever do anything which is not based on an evil and malignant personal purpose…” At the conclusion of his unbridled soliloquy, Abou Tannous declared the coming of a revolution: “You teach us obedience and humiliation, and in a short while we will teach you how clemency coexists with power, how meekness intertwines with authority, and love with liberty, justice with knowledge, fairness with equality, and the uplift of the people with popular rule [al-Hukm al-cUmmumi.” ‘Afifa Karam, another mahjari writer and an early leading feminist, was less dismissive of religion but equally critical of “bad” priests. In her second novel, Fāṭima al-Badawiyya [Fatima the

Bedouin], she depicts two contrasting images of priests. One is distinguished by “bigotry, ignorance, and cowardice, who makes religion a cause of evils and rebellions.” What differentiates this archetype of priests from kindly ones is “evil and limited knowledge” as opposed to “great and good learning.”

But perhaps more troubling to religious groups than criticism leveled by intellectuals and writers in the Mahjar and Mount Lebanon, was the departure of some members of the church from the folds of the faith. We do not know the exact number of people who left for other religious sects, or simply abandoned their faith. However, the letters from the Mahjar to the Maronite Patriarch do point to a crisis of sorts. For example, in 1905 Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the community of “1500 Maronites” decided to sell their church after getting into arguments with two consecutive priests, Father Jibrail Korkemaz and Father Ni’mat al-Kifrnawi, and they had “abandoned their faith.”[xviii] In New York “only a handful” of the 2000 Maronites attended church on Sundays and holidays. Five years later later, Father Boulus Ibrahim wrote that the 3,000 Maronite of the Cleveland, Ohio diocese are in “sad state because they are spread out across many cities with no shepherd to anchor them in the faith of their forefathers.” Father Ni’matallah Jida’oun wrote in 1921 that his brother’s wife “left him and strayed from the moral ways and teachings of the church.” He quickly added in his report to Patriarch Howayek, that his brother married an “American Protestant woman” and has stopped attending the church. In Valdosta, Georgia, many local Lebanese immigrants started attending Methodist churches, while their counterparts in Lake City, Florida flocked to the local Baptist church. It is these latter cases of mostly unrecorded departures from the folds of the faith that greatly alarmed Patriarch Howayek and those members of the community who remained within the fold of the Maronite faith.

For Howayek, and other clerics, the bickering, complaints, attacks and departures, tied the future of the Maronite Church to the lives of immigrants thousands of miles away, and their pleas for assistance and action required responses. This was especially necessary when these same immigrants were sending back hundreds of thousands of dollars every year to their relatives and to the church. Thus, Patriarch Howayek admonished some priests, recalled others, and endeavored to produce a more educated and prepared generation of clerics who could deal with the rapidly changing world at home and in the Mahjar. As for his secular critics he excommunicated at least one mahjari “heretic,” and raised the tenor of his attacks on the “Free Masons” and “Liberals.” These attempts to control and shape the Maronite community in the diaspora culminated in a project to enumerate emigrants and priests in Mahjar, in 1919. Howayek dispatched Bishop Shikrallah Khoury to the Americas and asked him to: “write a report that details the number of churches and schools which they established, its financial assets and how many attend both, a list of the names of our immigrant children. We want you to especially look into the state of affairs of our children the priests who are spread out in those areas, and what they have in terms of authorization papers…and encourage those who are well behaved, and seek to straighten those who have fallen into disfavor with the local [ecclesiastical] leaders or causes doubts and problems, and arrange for them to return to the homeland.” This report was the beginning of a century long effort to extend greater control of the church into the spiritual lives of its immigrant congregants in the US and South America.

Conclusion

These contentions over the substance and limits of religious authority persisted over decades, and they occupied and shaped a good part of the lives of immigrants, and the institutions and hierarchy of the religious institutions. They engendered intense emotions and partisanship, and generated a broad spectrum of writings—petitions, newspaper editorials, articles, and books. In between these drawn lines and arguments, the rituals of religion—listening to Arabic and Syriac chants, inhaling the smell of incense, beholding real or made-up relics, and tasting special foods—created moments of transnational being where distances and boundaries were fleetingly irrelevant, and where the breathless flux of identity settled for a spell.

Reference List

1. Alixa Naff, Becoming American: The Early Arab Immigrant Experience (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1985), 2.

2. Kathy Jaber Stephenson, Dima Abisaid Suki, and Rayyan Abou Alwan Amine, Druze in America The Early Years: A Collection of Stories (Canada: The American Druze Foundation, 2015), 287.

3. The number of Orthodox churches is inflated in terms of its representation of communities who established churches. The Russy-Antaky debate in the late 1910s and 1920s caused many existing parishes to split in two. Most of these churches merged together again in the 1930s.

4. Sally Howell, Old Islam in Detroit: Rediscovering the Muslim American Past (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 45-47.

5. “Fr. John Saba,” Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese of North America, n.d., http:ww1.antiochian.org/fr-john-saba.

- Categories: