“A Boatload of Horses”: Alan Jabbour’s Family Immigration Saga

This blog was written by Folklorist, Sabra Webber. Webber is a professor emerita at The Ohio State University in the Department of Comparative Studies and the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures. She visited the Khayrallah Center in the Summer of 2018 while researching her former colleague and friend Alan Jabbour. She wishes to thank Ruth Ann Skaff and Marjorie Stevens for their research assistance.

Introduction:

Dr. Alan Jabbour, Syrian American, first told me of his grandfather’s travel to America with “a boatload of horses” back in the late 1970s when he made a brief visit to Austin, Texas, to meet with the folklore community there. I was at the time one of many folklore graduate students at the University of Texas. Alan had recently been named founding director of the American Folklore Center at the Library of Congress and was already an ethnomusicologist of note. He had been seeking out, studying, and learning from master fiddlers in the hills and dales of North Carolina, Virginia and West Virginia since his graduate school days at Duke in the late 1960s. However, since I had been studying Arab-Texan family immigration sagas at the time we met, he diverged from his academic specialties to offer some insights garnered from his own folklore studies as well as remembrances based on his identity as a first generation Syrian-American.[1] His story began with his grandfather, Abdullah Jabbour. Abdullah was the first Jabbour in his family to come to America from an-Nabk, Syria, on the edge of the Syrian Desert. He came, Alan said, bringing a “boatload”[2] of Arabian horses destined for the Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1893. (Of course, boats play a big role in many earlier immigration stories.) Coincidentally, about the same time, boats and immigration had come up courtesy of my fellow graduate student Nick Spitzer. He sent me a postcard from Lafayette, Louisiana, where he was studying Mardi Gras. He had encountered an Arab-American in a little shop who had joked to him, “[Y]ou know how people say they came over on a banana boat? Well, I came over on an olive boat!” That clever adaptation by the shopkeeper of an old folk saying made me smile, but a “boatload” of Arabian horses from the Syrian Desert seemed unique. This sounded like a true fairy tale to me, until in the next moment the story almost seemed to end before it started. Alan quickly put a blanket on my enthusiasm by adding, “[T]he horses contracted a disease one from the other, in the middle of the Atlantic, and [Abdullah Jabbour] arrived in New York horseless and presumably penniless.” Alan then added, “The story as…I received it gave the faint impression that [my grandfather] was a visionary dreamer…and this was yet another example of a crazy dream that…somehow never quite worked out.” It was not until very recently that I started to wonder. Was it a crazy dream? Did Abdullah and the horses never get to Chicago? After all, Mody Boatright, the Texan folklorist who coined the term “family saga” cautioned that in these stories, often garnered in childhood, are not historical “truth” but encapsulate the essence or spirit of a family over generations.[3] More about that later.

Folklorists like me look for the “performative” elements of a story. What is it that strongly affects a particular audience? We recognize the “banana boat” motif and appreciate the clever adaptation by the Arab-Louisianan shopkeeper to a Middle Eastern stereotype that Nick, a 1970s “hippy-American” graduate student, (and I too) would appreciate. In earlier blogs from the Khayrallah Center writers allude to reasons for leaving the “old country” like fear of conscription or persecution—sad, not necessarily “performative,” stories that focus on the most recognized cry of the Statue of Liberty, “send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me.” Then there are the images of adventurous, even swashbuckling, risk-takers—those youths in all families who alarm their loved ones. Those young adults, like Alan’s grandfather or the still somewhat mysterious to me Annie Coury Abdo seemed pulled toward the wider world. Then there were those pushed toward the wider world—expelled from the old world as undesirables like my long ago ancestor who, supposedly, was kicked out of Scotland for stealing sheep. Whether pulled or pushed, appealing immigration stories of whatever sort do not usually consist of folks bumping up on the eastern shores of the new world with pockets full of gold. In fact, those who bump up with those pockets full of gold tend to be objects of suspicion.

So, what are the “performative” elements of Alan’s family immigration account? What draws us toward a family immigration saga that is not of our own family?

Three Decades Later:

Although we crossed paths now and then, I heard no more of Alan’s family immigration saga until 2006. That year, I and four other folklorists[4] heard, or perhaps a better word would be “elicited” a much more detailed story. I was teaching an Ohio Humanities/Ohio State supported Summer Institute for Ohio high school teachers titled, “Arab-American Family Immigration Sagas.” Recalling Alan’s story from many decades earlier, I invited him to the Institute as a guest speaker. After we treated the students to a special Mashriqi (Eastern Arab Food) dinner, Alan played his fiddle for them and the following day, in the classroom, he chatted with them about his family immigration saga. Finally, taking advantage of his presence with us and in the guise of a fireside chat, we five folklorists filmed a ninety-minute interview with Alan, a much more detailed story of his family’s immigration and the family’s eventual interweaving of Syrian and American lives. The story began as it did each time I heard it in medias res—on the boat, with the horses—betwixt and between the old and the new worlds. But in this filming he gradually surrounds that story with new details. He speculates about his grandfather’s time in New York and eventual arrival in Jacksonville, Florida, where Alan was born, tells us more about Albert Jabbour, son of Abdullah and Alan’s father, and at last to memories of his own youth in Jacksonville. From time to time he “breaks into performance” as folklorists say, briefly acting the part of the first Jabbour, or of a Jacksonville resident from an-Nabk who has lost her culture (lben/yogurt), or his Aunt Lily’s intervention into an argument about how to make coffee, or his parents’ courtship and so on. These I can share in another blog as I want to get back to the horses who played such a big role in the imaginary of Abdullah’s voyage and Alan’s recounting of it.

The Arabians’ Family Immigration Saga

Happily the best horses of the Syrian Desert, the pride of Syria, did not die at sea. How do we know? Abdullah Jabbour told us. Alan, after his comments about the failure of the Chicago Fair plan remarked in passing that his grandfather “apparently started an Arabic language newspaper in Brooklyn.” This led me to look, while working at the Khayrallah Center, for newspapers edited by or articles written by Abdullah Jabbour. The staff at the Center pointed me toward Kawkab Amirka, an important early Arabic language newspaper out of New York. There I found what turned out to be a rich source of accounts by Abdullah Jabbour–some reading like a diary or journal and sometimes like a report for officialdom. As another Texan folklorist, Francis Abernethy pointed out, the sagas are not history, but “shadows of history” which, he goes on to say, are in a sense “more important than the details.” Yet, as I have observed in my work in North Africa and as Abernethy also observed for his studies in Texas, family history is found not only through oral stories, but also by way of a “journey through time in the form of letters, diaries, memoirs, and journals.” [5]

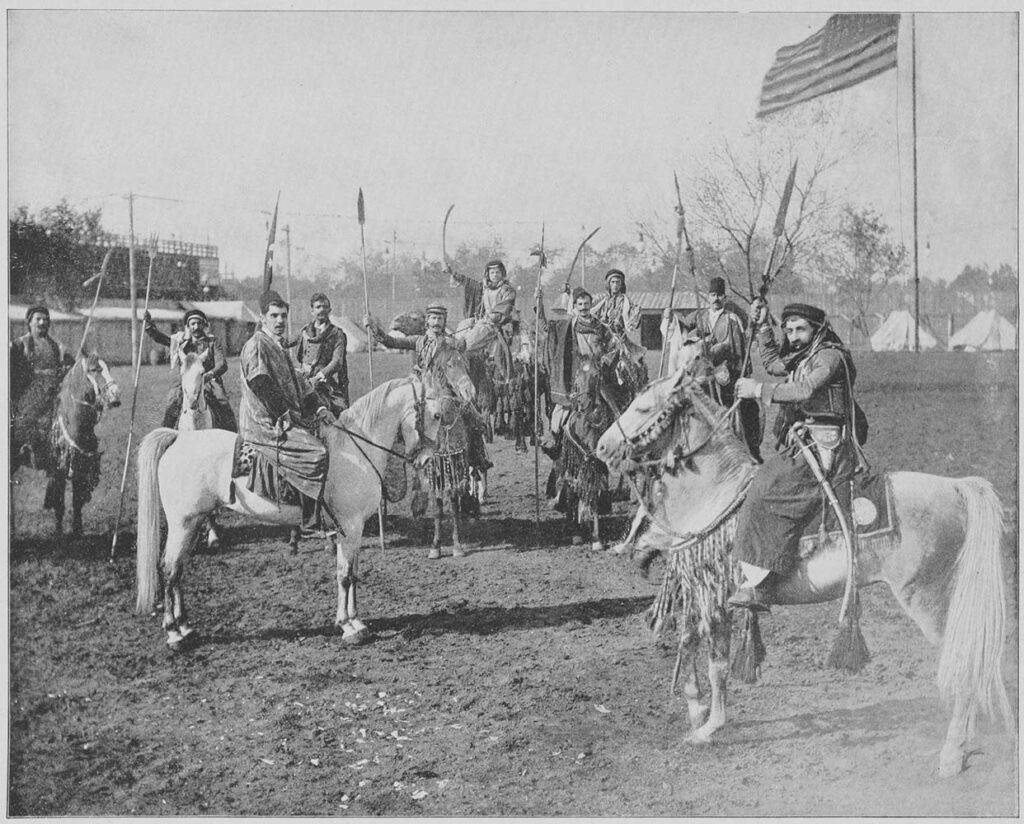

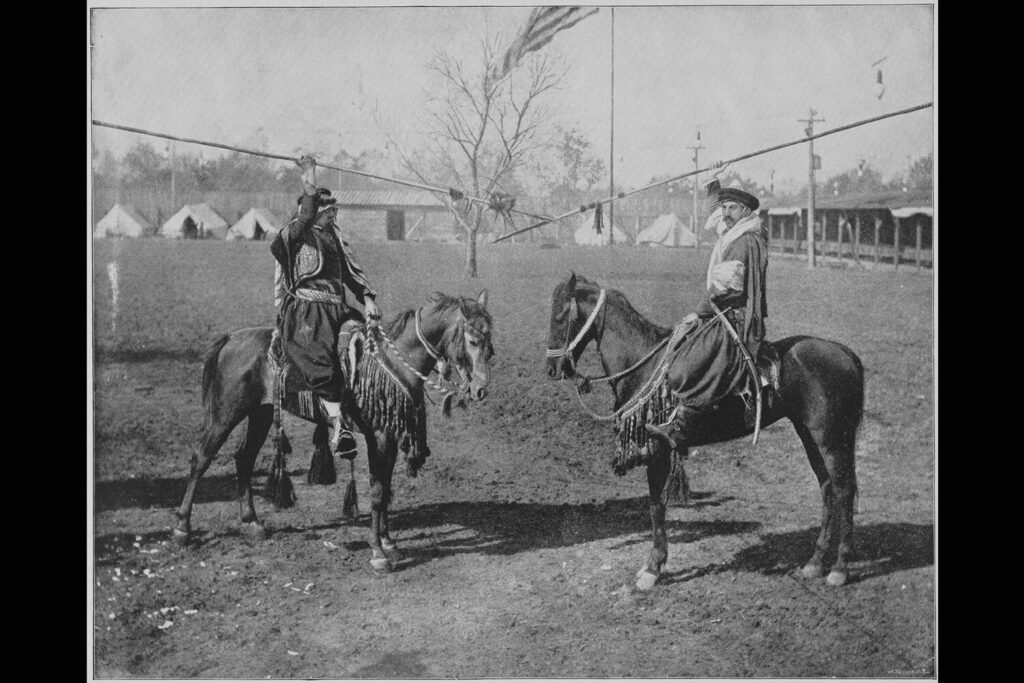

In Kawkab, Abdullah writes appealingly of his trip through the Mediterranean and across the Atlantic as well as of the time he spent in Chicago at the Fair and all the troubles with the finances (and a hint of rivalry[6] between the Buffalo Bill troupe and that of the Syrians).[7] The ship Alan referred to turns out to be the Cynthiana. It carried, along with 50 Arabian horses,[8] 274 people, 23 of them women, as well as camels and donkeys bound for the Chicago Fair. Abdullah writes that they anchored in New York on April 25, 1893. From there they made their way by train to Chicago.

As happens with oral stories, perhaps especially in the understanding of young listeners, events may be conflated. Sadly, horses did die, as Alan must have heard his father relate when he was a young lad, and many of the Syrians wound up penniless. However, all the horses did not die and it seems most, if not all, did make it to the Chicago Fair. Seven died, but not from an infectious illness and not at sea. They died in a fire on the fairgrounds on June 17, 1893[9], a precursor to a much larger fire the following month on July 10, in which 16 people including 12 firefighters died. Although Abdullah was not the only writer who reported about the fire and the deaths of the horses (and half the camels), his report was the most eloquent. Perhaps as a lad growing up on the edge of the Syrian Desert with pride in the Bedouins’ Arabians, his report reveals not only regret at their deaths, but also implies a tenderness that the horses had for each other and he for them. “It was said that the horses, when the fire surrounded them, gathered together dying in unison at the hour of despair. For the charred remains of their bones were in one spot.” Some other horse deaths Abdullah blamed on Chicago weather.[10]

Arabians–Immigrants Today: The horses were contracted to go home to the desert after the Fair, but the pennilessness that Alan remembers was a very real problem. Abdullah goes on at some length in his articles about the frustrations of Syrians trying to deal with finances at the Fair. In desperation, the Syrians finally auctioned the horses. Not surprisingly, Arabian horses were a major source of interest at the fair, the “point from which interest in the Arabian horse [in America] was created….” Two horses, a mare, Nedjme, and a stallion, Obeyran, are the number 1 and number 2 horses “of the official registry studbook.”[11] Their offspring were, in official records at least, the first-born Arabians in the new world. Several other horses were also entered in the studbook and the shenanigans regarding use of written records, oral testimony and assessment of the horses’ appearances to assess their “pure Arabian” status that Abdullah and others recount is not for me to sort out. However, today there are more Arabians registered in North America than in all the rest of the world.

To be continued…

Notes

[1] http://dukemagazine.duke.edu/article/alan-jabbour-am-66-phd-68 .

[2] All quotes from Alan Jabbour are taken from the transcript of the 90 minute filmed interview. Folklorist, Mike Luster transcribed the film dialogue.

[3] Mody C. Boatright, The Family Saga and Other Phases of American Folklore (Urbana: The University of Illinois Press, 1958).

[4] The folklorists, in addition to me and to Alan, were Pat Mullen, Barbara and Tim Lloyd and Sheila Bock. In a subsequent blog, it will become clear how important an audience is in what stories are told and how.

[5] Abernethy, Francis Edward, Jerry Bryan Lincecum, Frances B. Vick, eds. The Family Saga: A Collection of Texas Family Legends. Publications of the Texas Folklore Society LX University of North Texas Press, Denton TX 2003 (p. 3).

[6] Abdullah Jabbour column, Kawkab Amirka vol. 2 no. 99 (3/9/1894).

[7] Dr. Christopher Hemmig did all translations of Abdullah Jabbour’s newspaper articles for me.

[8] The numbers of people, horses and so on quoted by various sources differ slightly. I use Abdullah’s when they are available.

[9] This is not the date Abdullah gives, but it is the date other sources seem to agree on.

[10] Abdullah Jabbour column, Kawkab Amirka vol. 3 no. 104 (4/13/1894).

- Categories: