Dr. Alixa Naff

Pioneer of Arab American Studies.

Dr. Alixa Naff: A Founder of Arab American Studies

By Rosemarie M. Esber, Ph.D.

Dr. Alixa Naff is considered the mother of Arab American Studies. She believed that the Arab American immigrants’ experience was important to research. When Alixa found that primary materials were non-existent, she went out and collected and preserved oral histories and artifacts. Her archive established the Faris and Yamna Naff Arab American Collection at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. to preserve the early history of Arabic-speaking immigrants to the United States and to encourage ongoing research in the field of Arab American Studies. (Photo in header: Arab American National Museum Collection 2004.06.02a)

Alixa was born September 15, 1919 in Rashayya al-Wadi, a village in the Anti-Lebanon—the western mountain range of the former Ottoman province of Syria, in modern-day Lebanon. Her parents, Faris and Yamna Naff, immigrated with their two little girls to the United States in 1921. They arrived on January 1, 1922 in Spring Valley, Illinois—a small, rural town where several Rashayyan families had settled prior to 1910. Her father Faris had peddled in the Midwest from 1895 to 1913 and knew the area. He returned a widower to Rashayya in 1913 to care for his 90-year-old ailing mother, and there, he remarried. His young bride, Yamna Ghantous, was the daughter of a wealthy landowner. In 1922, Faris resumed peddling, this time from a Model T Ford, using Spring Valley as his family’s base. (Photo Above: Arab American National Museum 2004.06.02b)

Tragedy struck the family several times in the 1920s. Yamna lost at least two infants and her parents were murdered in 1925 during the Christian and Druze rebellion in French mandate Syria. Yamna would wear mourning black for 17 years. In 1929, the family moved to Fort Wayne, Indiana, where they had relatives. Faris opened a grocery store, which failed in less than a year. The growing but struggling family sent 10-year-old Alixa to live with her half-sister Nazha in Detroit. Alixa was lonely and miserable without her family. She developed “a strong appetite for reading and a passion for words, their use, sounds, and meanings.” She spent most of her time reading books and newspapers, and clipping poetry, pictures, drawings, and wisdom, listening to Arabic music, and daydreaming about faraway places.

“The virtues of generosity, hospitality, and compassion we learned from example.”

– Dr. Alixa Naff

In June 1931, her father moved the entire family to Detroit, where he launched a series of efforts at the grocery business. Detroit was Alixa’s hometown from 1930 to 1950 and where, she wrote, “my sister, my three brothers, and I developed as individuals.” She was profoundly moved by the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow poem, “We are Seven.” It described the Naff family, “for we too ‘are seven’ and two of us also ‘in the churchyard lie.’” The family values “were all drawn from Rashayyan tradition and the Bible: honesty, truthfulness, respect for our elders, and honoring the family name. The virtues of generosity, hospitality, and compassion we learned from example.”[*]

Alixa later recalled, “Who of the millions of afflicted did not share in the hope of the New Deal and the anxieties of World War II, or wonder at the seismic social and economic changes of the postwar period?” The 1930s and 1940s were as critical for the Naff family as they were for the entire country. She wrote, “I am awed at how my immigrant parents pulled us through those difficult times. I marvel at their native survival instincts and the strength they drew from their Syrian–Lebanese traditions and customs.” Because they persevered, “we survived as a family—intact and Americanized.”

“I am awed at how my immigrant parents pulled us through those difficult times.”

– Dr. Alixa Naff

In 1942, the family home became 57 Tennyson Avenue in Highland Park, Michigan with land enough for fruit trees and a vegetable garden to feed the family and many guests year-round. Throughout her high school years, Alixa admitted that “I was ashamed of my immigrant appearance—hand-me-down clothes and long, coarse, black, wavy hair. And Mother, dressed in black from head to toe and unable to speak English, had the stamp of immigrant all over her.” Alixa’s habits of daydreaming and reading led to a special interest in English literature and composition in school and to life dreams that diverged from traditional expectations for Syrian women in America.

Alixa “desperately wanted to attend college.” Although her mother insisted that her sons go to college, “extending that privilege to me was inconceivable.” Alixa went to work for Western Union in Detroit for several years and credited the experience “as my passage into the real world.” There, she learned “what the children of nonimmigrant Americans were like.” And in their company, she wrote, “I ceased to be just the shy daughter of an immigrant grocer. I developed a personality and some confidence.” Alixa was working the Sunday Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, but she did not grasp the gravity of the situation or relate it to her life in that moment.

During World War II, while her two brothers served in the army and the navy, Alixa was forced to manage the family grocery store. And with “unwavering dedication,” she “wrote to ‘the boys’—twenty-five of them—into the small hours of the night,” including her Marine boyfriend. After the war, the eldest son was reassigned to California, and could not be persuaded to return to Detroit to work at the family grocery store. Instead, he encouraged his family to join him in California. It was an appealing idea, especially after Alixa and her parents visited Los Angeles. The Naff family had been harassed by their neighbor, a former Ku Klux Klan member from Tennessee, who tried to prevent blacks from moving into Highland Park by vandalizing neighborhood houses and burning garages.

Her mother died suddenly in April 1949. Grief stricken, Alixa sold the grocery store and the house and moved to California with her 74-year-old father in 1950. She encouraged him to write his life story in Arabic in a brown spiral-bound notebook as part of the grieving process. Faris Naff’s memoir begins: “My father died in 1872 and left my mother with nothing.”

University Education and the Collection’s Beginning

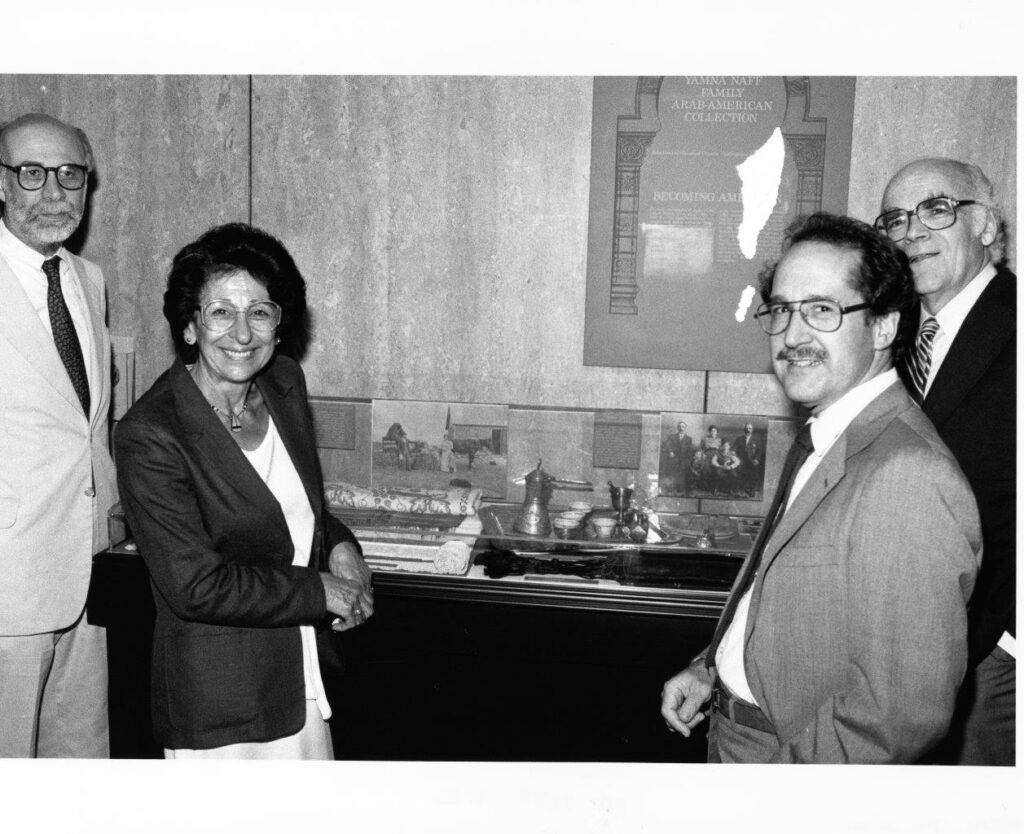

After a decade of private sector work in business administration, Alixa enrolled at the University of California, Los Angeles in the late 1950s, seeking a bachelor’s degree. For a senior year American history seminar on immigration, Alixa wrote about the Arabs in America. Because of a lack of scholarship, Alixa based her research on interviews with her parents’ friends. Her professor, impressed by her research efforts, facilitated a grant for her to collect oral histories and folklore from Arabic-speaking immigrants. (Photo to the right: Naff Arab American Collection, Smithsonian Museum)

During the summer of 1962, with $1,000 and her cassette tape recorder, Alixa drove in her blue Volkswagen beetle—dubbed “the camel”—to 16 communities with Arab immigrants in the United States and eastern Canada. She recorded interviews with 87 elders—as many of the remaining members of the first wave of Arabic-speaking immigrants to North America as she could reach. Alixa said she had “discovered the mother lode of Arab life histories, a record of the vitality of their ethnic life in America.” She was fascinated and captivated by the immigrants’ experiences and their delight in relating their stories. She also collected artifacts, newspapers, and pictures, which were the beginnings of the Naff archives.

Photo to Right: Smithsonian, Faris and Yamna Naff Arab American Collection; NMAH.AC.0078)

Like so many other Arab Americans, the 1967 Arab–Israeli war affected the development of Alixa’s identity. “I was in my office when I first heard about the war,” she wrote. “A friend came in and said ‘Alixa, you better go home, they’re out to get you.’ I didn’t understand. At that time, I ate the [Arabic] food and I loved the dancing, but I was an American. All of a sudden, we all became Arabs.”

Alixa continued her studies and earned a master’s and then her Ph.D. degree in 1972. Her dissertation, “The Social History of Zahle, the Principal Market Town in Nineteenth-Century Lebanon,” was based on oral history fieldwork in Lebanon. Alixa taught at California State University, Chico, and the University of Colorado at Boulder but left academic teaching in 1977, citing anti-Arab attitudes on campus and nationally. She wanted a more active role in countering anti-Arab stereotypes with accurate information. She contacted The Washington Post, The New York Times, and members of Congress to ask, “Where are you getting your information about Arab Americans?”

Scholar, Oral Historian, Archivist, and Activist

In 1977, Naff moved to Washington, D.C. to consult for a documentary about the Arab American experience. The project highlighted the lack of primary source materials. Alixa was painfully aware from her field research that families often threw away papers, artifacts, and photographs. She worried they viewed the “history of their American experience [as] too insignificant and too fleeting to warrant recording” or study. Alixa continued her artifact collecting efforts while initiating a more in depth study of the history of Arab immigrants. (Photo to the right: Cover page of Dr. Alixa Naff’s book)

In 1979, Alixa Naff met Gino Baroni, an undersecretary at the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development and the founder of the National Center for Urban Ethnic Affairs. The center facilitated grants for her research from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Her 1985 book, Becoming American: The Early Arab Immigrant Experience was a result of her research. Alixa also contacted Richard Ahlborn, then curator of the Smithsonian’s Community Life Division, about donating her growing collection of interviews and artifacts to the Smithsonian. She gifted her collection to the Smithsonian Museum of American History and named it after her parents Faris and Yamna Naff. At the ceremonial opening of her collection in 1984, Alixa joked that the inauguration was “more important than her funeral.”

Alixa attached explicit conditions to her gift to the Smithsonian, including: the collection would be preserved, expanded, made available to students and scholars, and exhibited periodically to the public. For decades, Alixa was a dedicated volunteer archivist of her own collection at the Smithsonian, assisted by a number of Arabic-speaking volunteers who helped to catalog the collection. She frequently travelled the country lecturing about the collection and her research, and when opportunities arose, she persistently and persuasively always attempted to obtain additional artifacts for the Naff collection.

The Faris and Yamna Naff collection is preserved at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History Archives Center. It contains 500 artifacts, including religious artifacts, musical instruments, and recordings. There are at least 120 cubic feet of documents, including 450 oral history interviews, and more than 2,000 photos, as well as articles, newspapers, dissertations, and books documenting Arab immigrants’ lives from 1880 to World War II. Alixa’s greatest hope for her collection was that a new generation of researchers “will come along and use this and write the next chapter.”

Alixa’s hopes for the Faris and Yamna Naff collection have been realized. The Arab American National Museum in Dearborn, Michigan, digitized her oral history interviews after her death on June 1, 2013, to honor her and to make them more accessible. A few months before she died, an Arab American Studies Association was established with regular conferences, where the Naff collection and Alixa’s research have been frequently discussed. National and international students and scholars utilize the collection as a primary reference for dissertations, books, articles, museum exhibits, and films. Universities have established Arab American studies programs and the field of study continues to grow. In America, the daydreams of an immigrant grocer’s daughter, and an eminent and beloved scholar, have been fulfilled.

Rosemarie M. Esber, Ph.D.

July 1, 2020

[*] Quotations are from Alixa Naff. “Growing Up in Detroit” in Arab Detroit: from Margin to Mainstream. Nabeel Abraham and Andrew Shryock, eds. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2000.