How the Lebanese Became White?

This post is written by Dr. Akram Khater, Director, Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies. Dr. Khater is a professor of history at North Carolina State University and has published extensively on Lebanese migration to the United States.

Race is a difficult topic. It is fraught with a violent history and tumultuous feelings. Yet, race was a central element in the Lebanese immigrant experience, not only in the Jim Crow South of the US, but in Africa, Australia and South America.

The Lebanese left homes in Zahleh, Dayr al-Qamar and other villages and towns where their sense of self was anchored in their community, family and religion. Race–as a biological marker of ability, social opportunity and rank–was not something they had encountered until they arrived here, and other parts of the mahjar (land of emigration).

Coming into the Jim Crow South (or the equally racially segregated South Africa and Australia) Lebanese immigrants faced discrimination, harassment and in few cases even worse. As Phillip Shehdan noted “there were three things you did not want to be in North Carolina [in the first half of the 20th century]: a foreigner, a Catholic [or Eastern Christian] or black. The Lebanese were two out of those three!!!” Examples of this bias abounds. Speaking of the “Syrian” [a generic term applied to all immigrants from today’s Lebanon and Syria] a writer in the Wilmington Messenger wrote: “These foreigners are…filthy and immoral in their habits, breeding pestilence and filth wherever they live.” (June 23, 1897). American Nativists, worried about the “immigrant menace”, lashed out at the Lebanese and other ethnic communities. In the charged environment of racial politics of the South, Alabama’s congressman John L. Burnett argued in 1907 that the Lebanese “belong to a distinct race other than the White race.” In 1914 North Carolina Senator, F. M. Simmons went further proclaiming: “These [Lebanese] immigrants are nothing more than the degenerate progeny…the spawn of the Phoenician curse.”

This hostility toward the Lebanese (as well as Black, Italians and other non-whites) in the South sometimes led to tragic and violent events such as the lynching of Nola [N’oula] Romey in Lake City, Florida in 1929. Nou’la had immigrated with his wife Fannie from Zahleh to Valdosta, Georgia around 1906. They decided to move to Lake City, Florida in 1926 after N’oula was flogged by the local KKK chapter, and after several run-ins with the law in Valdosta. Unfortunately for the family, problems with the law persisted in Lake City, and came to a head when the Sheriff and his deputies shot Fannie to death over an altercation at the Lebanese couple’s store. They then placed N’oula in jail where later that night a mob dragged him out and killed him.

These verbal and physical attacks on the Lebanese in the South mobilized the community to defend itself against defamation and discrimination. For instance, H. A. Elkourie, a physician and president of the Syrian Young Men’s Society in Birmingham, Alabama responded to Congressman Burnett’s aspersions in several editorials published in the local press. Similarly, in Wilmington Haykal Gideon [Jad’oun] wrote a scathing response to the editorial accusing the “Syrians” of being filthy and immoral, and pronouncing himself and his community to be law-abiding and hard-working parts of the community.

While individuals and even local Lebanese organizations did respond to these attacks, the larger Lebanese-American community in the United States did not formulate a coherent and coordinated response until the naturalization case of George Dow, a “Syrian” immigrant living in South Carolina. George Dow, who was born in Batroun (north Lebanon) in 1862, immigrated to the United States in 1889 through Philadelphia and eventually settled in Summerton, South Carolina where he ran a dry-goods store. In 1913 he filed for citizenship which was denied by the court because he was not a “free white person” as stipulated in the 1790 US naturalization law.

For the “Syrian” community this case was crucial because it could mean the end of their ability to become US citizens, and thus maintain their residence and livelihoods in “Amirka.” Moreover, it was a matter of equality in rights. The community’s struggle with the fluid concept of “free white person” began before George Dow, with Costa Najjour who was denied naturalization in 1909 by an Atlanta lower court because he was too “dark.” In 1913 Faris Shahid’s application was also denied by a South Carolina court, because “he was somewhat darker than is the usual mulatto of one-half mixed blood between and the white and the negro races.” In rendering his decision in the Dow case, Judge Henry Smith argued that although Dow may be a “free white person,” the legislators from 1790 meant white Europeans when they wrote “free white person.”

The “Syrian” community decided to challenge this exclusionary interpretation. Setting aside their differences, all Arab- American newspapers dedicated at least one whole page to the coverage of this case and its successful appeal to the Fourth Circuit court. Al-Huda led the charge with one headline “To Battle, O Syrians.” Proclaiming that Judge Smith’s decision was a “humiliation” of “Syrians,” the community poured money into the legal defense of George Dow. Najib al-Sarghani, who helped establish the Syrian Society for National Defense in 1914 in Charleston, South Carolina, wrote in al-Huda, “we have found ourselves at the center of an attack on the Syrian honor,” and such ruling would render the Syrian “no better than blacks and Mongolians. Rather blacks will have rights that the Syrian does not have.” The community premised its right to naturalization on a series of arguments that would “prove” that “free white person” meant all Caucasians, thus establishing precedent in the American legal system and shaping the meaning of “whiteness” in America. Joseph Ferris summarized these arguments a decade later in The Syrian World magazine as follows: the term “white” referred to all Caucasians; George Dow was Semite and therefore Caucasian; since European Jews (who were Semites) were deemed worthy of naturalization, therefore “Syrians” should be given that right as well; and finally, as Christians, “Syrians” must have been included in the statute of 1790. The success of these arguments at the Court of Appeals level secured the legal demarcation of “Syrians” as “white.”

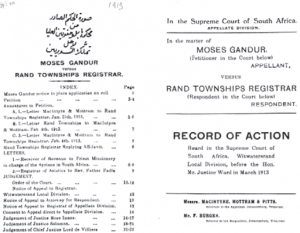

What makes this particular story more remarkable is that similar ones were unfolding around the same time in South Africa and Australia, both of which had racially-based definitions of citizenship and concomitant rights. For example, in 1913 Moses Gandur challenged the classification of “Syrians” as “Colored Asiatics” before the Supreme Court of South Africa and won by arguing that although “Syrians” resided in Asia they still were white or Caucasian, and thus not subject to the exclusionary clauses of the 1885 Law. In all of these cases, the arguments were also quite similar to the one summarized by Joseph Ferris above.

These decisions meant that the “Syrians” (and by extension today all Arabs) are considered white in the US. This entry into mainstream society–where whiteness bestowed political and economic power–meant different things for different members of the Lebanese community. Some were satisfied to leave the racial system of the South unchallenged as long as they were considered white.

For others, the experience of fighting racial discrimination convinced them that the system is inherently unjust and must be changed. Thus, many NC Lebanese (like Ralph Johns who encouraged his black clients at his clothier store on East Merchant Street to start the sit-ins in Greensboro) participated in the Civil Rights struggle of the 1960s to end the era of the Jim Crow South.

Today we live in a far more multi-cultural society where diversity and ethnicity are celebrated by most Americans as positive aspects that enrich our country economically, politically and culturally. In part this was due to the struggles of our early immigrants, but also to the continuing work of high-profile activists like the late Helen Thomas, Edward Said, Ralph Nader and a myriad of local and national organizations that raise the profile of our community within the larger society.

For a detailed history of race and Lebanese immigrants to the US you can read Sarah Gualtieri’s book, Between Arab and White.

- Categories: