Spanish Flu Grips Vermont’s Young Lebanese, 1918

This post is written by Marjorie Stevens, Assistant Director and researcher for the Khayrallah Center. Her last article was on the Creighton-Danby Collection at the Gregg Museum.

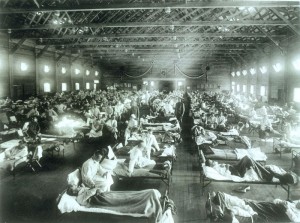

In 1918, one of the most devastating pandemics in history ravaged the world. Roughly three to five percent of the global population died, or fifty to one hundred million people. By some estimates this is more people than were killed by the Black Death. Examining Lebanese immigrants affected in Vermont, we see the flu’s detrimental impact on young lives and families striving to establish themselves in America.

Spanish Influenza, as the disease was known, was a strain of H1N1. It got its name because Spanish newspapers reported the disease most widely since Spain was not engaged in World War I. Other European countries kept reports of the flu’s devastation out of papers to boost morale. It is unclear where the pandemic began, but the constant movement of troops during the war and modern transportation spread the disease very quickly throughout the world. Theories vary, claiming the disease originated in France, Kansas, and China. The flu was first reported in the United States in January of 1918 in Kansas and was noted in New York City by March. From Northeastern hub cities the epidemic spread into Vermont. In Vermont, 35,954 cases of influenza were reported and 1,772 deaths in 1918. The Spanish Flu struck Vermont’s Lebanese immigrant population very hard. Out of all Lebanese immigrant deaths in 1918, ninety-one percent were due to the Spanish Flu. Out of all Lebanese immigrants who died in Vermont between 1909 and 2008, three percent died of the flu in 1918. However, the Spanish Flu was most devastating to these immigrants because it affected adults in their prime most severely. This was likely because the disease prompted the immune system to go into overdrive and since the immune systems of young adults were the strongest, their systems were most stressed by the illness. Nearly fifty percent of deaths from Spanish Flu occurred in people ages twenty to forty. In Vermont, ten out of the eleven Lebanese victims fell in this group and one was aged fifty-four. Compared to typical flu epidemics that mostly affect the very young, very old, and infirm, the Spanish Flu was unique. Many Lebanese immigrants residing in Vermont (and throughout the country) fell within this most vulnerable age group.

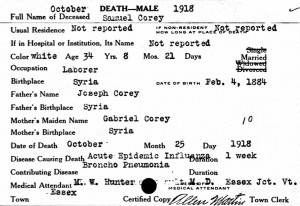

At the prime of their lives, they were struggling to establish themselves and their young families in the United States. The lives of these young adults were so important not only because they were loved but also because their lives were vital to their dependents. As a result of young lives lost, families were broken and placed under immense hardships. Sam Corey, 35, of Essex Junction and Burlington passed away on October 25th leaving his wife and five children ages two months, four, six, eight, nine, and ten. In 1920, his wife Mary, now a single mother, worked to support her family at a woolen mill. Her three oldest children, Dora, Eva, and Arthur lived with her but under what must have been devastating circumstances, she was forced to place her two youngest, Emmaline and Bernard in Burlington’s Home for Destitute Children. Her infant, Annie, had died shortly after her father in December of 1918. Just next door to Mary Corey, the Hendy family had also suffered losses. Two brothers, Anthony and Joseph immigrated in 1914 and settled together in Burlington. They were sons of Sarah Corey and Reverend Elias Hendy. Elias, 54, died of the flu in December, 1918 while Joseph’s infant son Raymond had suffered from the flu in January and died of Bronchitis in March of 1919.

The Home for Destitute Children in Burlington housed four other children of Lebanese immigrants in addition to the children of Mary Corey. These children numbered among 440 orphans in Vermont according to a 1919 survey and accounted for eight percent of the Burlington orphanage’s population. Joseph and James George, whose father had died of Tuberculosis in 1918 (the one death of a Lebanese immigrant in 1918 not attributed to influenza), and Elizabeth and Thomas Raymond had also been turned over to the care of the children’s home. Elizabeth and Thomas Raymond, like the Corey’s, were the youngest children of a parent widowed by influenza. Wady Mike Raymond lost his wife, Annie Abdallah Syha, 30, on November 13, 1918. Due to the loss of his wife, Wady had to split up his family leaving the two youngest behind in Vermont while moving to Lawrence, Massachusetts to work as a shoemaker with his seven year old son Azizey. The four children of Jerry Mike Shadea, 35, and Lehaya Corey, 27, of Barre were completely orphaned when their parents died just five days apart from each other in September and October of 1918. Our research has found no record of Jerry Jr., Annie, Emmaline, and Josephine Mike Shadea after 1918. It is possible they were sent back to Lebanon to close family members or their names were changed. Albert George, 35, a grocery merchant in Burlington, left behind his wife Rose Masi and three small children. Rose was running the store herself in 1920. Other Vermont Lebanese victims of the Spanish Flu were:

- Martha Allen, 23 of Burlington

- Rosie Raymond Brice, 27 of Burlington

- Said Corey, 20 of Barre

- George E. Joseph, 24 a soldier serving at Fort Ethan Allen in Chittenden County

- Daniel Romanos, 29 of Barre

- Sammy Handy, 10 of Newport (child of immigrants)

Fortunately for Lebanese-Americans who lost love ones to Spanish Flu, strong ties to immigrant communities made it mostly possible for them to stay in the United States. The same systems of family kinship that helped immigrants find a place in the United States, were there for support as they struggled through trying times.

Sources

Duffy, John J., Samuel B. Hand, and Ralph H. Orth, eds. The Vermont Encyclopedia. University Press of New England, 2003. Kirby, Chris. Spanish Influenza as Reported in the Middlebury Register. Vermont Digital Newspaper Project, 2014. http://library.uvm.edu/vtnp/?p=1610 (accessed February 24, 2015).

Wheeler, Scott. The Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918. Vermonter.com. http://www.vermonter.com/northlandjournal/spanish-flu.php (accessed: February 24, 2015).

Woodsmoke Productions and Vermont Historical Society, “The 1918 Flu Epidemic,” The Green Mountain Chronicles radio broadcast and background information, original broadcast 1988-89 (accessed February 24, 2015).

- Categories: