Meet the Khayrallah Center’s New Post-Doc Fellow: Lily Balloffet

This interview was conducted over email with Caroline Muglia, who works with the Khayrallah Center. Lily Balloffet is the winner of the 2015-2016 Middle East Diaspora Post Doctoral Fellowship, a prestigious award that is open to scholars in the humanities and social sciences whose scholarly work addresses any aspect of Middle East Diasporas. Lily’s fellowship begins on August 1, 2015 and ends May 31, 2015. The Center congratulates Lily on her major contribution to the field!

What drew you to your dissertation topic of Arabic speaking immigrant communities in Argentina? I was initially drawn to the late nineteenth and early twentieth century time period in Argentine history long before I knew I wanted to focus my work on Arabic-speaking immigrant communities. This era in Argentina represented a massive immigration boom that caused the population to double from approximately 4 million to 8 million people between 1895 and 1914. At the turn of the century, immigrants accounted for as much as half the population of various Argentine provinces. My own ancestors immigrated to Argentina from France and Spain in the nineteenth century, and for as long as I can remember I have been fascinated by the stories passed down to me by family members about the experiences of those individuals. In choosing my dissertation topic, however, I wanted to focus on an ethnic community whose past does not have such an extensive amount of academic studies dedicated to their history in Argentina – as is the case with larger immigrant communities such as the Italians and Spaniards.

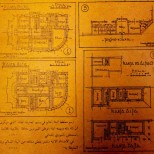

A lot of your work centers on identity—language, place, and intellectual collaborations—can you talk about how you explain the complex notion of ‘identity?’ In my work I try to draw out the connections between culture and identity, and the ways in which they intermingled and influenced one another in the lives of immigrants from the Levant and their descendants. Beginning in the earliest published Syrian- and Lebanese-owned newspapers, books, and magazines in Argentina, the subject of the identity of their “colectividad” [ethnic community] was often at the forefront of editorials, charity campaigns, festivities, and intellectual debates. After beginning my research, I realized quickly how much of an oversimplification it would be to pit these individuals’ “Syrian,” “Lebanese,” or “Arab” identity in opposition with their constant struggles for social citizenship and the right to claim identity as “Argentines” alongside the other millions of immigrants who hailed from across the globe. Instead, I believe that their efforts to integrate their community into the political and economic fabric of Argentine society worked alongside their constant concern with the preservation of their cultural heritage to mutually inform the “identity” of their community. The Arabic language was of course a central concern to many immigrants, and efforts to build language schools in order to teach future generations to communicate in Arabic give us a sense of how enmeshed language was with Syrian and Lebanese identity for many members of diaspora communities throughout Argentina and the Americas in general. While the Arabic language was a common denominator for the first generation of Arabic-speaking immigrants in Argentina, many second- and third-generation Syrian- and Lebanese-Argentines grew up speaking Spanish, and there were many more children in the colectividad than there were desks in Arabic language school classrooms.

The Center’s major focus is tracking diasporic communities, which is not easy. Can you talk about what drew the Arabic-speaking communities to South America, and Argentina specifically? One of the reasons that Argentina experienced such a massive immigration boom in the late 19th century was that the Argentine government was heavily encouraging immigrants to come there. For such a large geographic territory (Argentina is approximately one third the size of the continental U.S.), Argentina was very sparsely populated, especially after the death toll of nineteenth century conflicts such as the Wars of Independence. Across race and nationality, these people set their transatlantic course in hopes of “making it in America.” In the United States, it is often easy to fall into the trap of thinking that the idea of “making it in America” is a concept specific to this country – it is not! In fact, language barriers, dishonest travel brokers, and a host of other reasons often combined in such a way that Arabic-speaking immigrants departing from major port cities such as Marseilles only knew they were boarding ships bound for “America.” Whether these ships were in fact bound for New York, São Paulo (Brazil), Buenos Aires (Argentina), etcetera, was a detail revealed to the passengers upon their disembarkation at the other end of a harrowing journey. This is not to say that Arabic-speakers by and large came to Argentina “by accident” – there were also many people who conscientiously chose to go there.

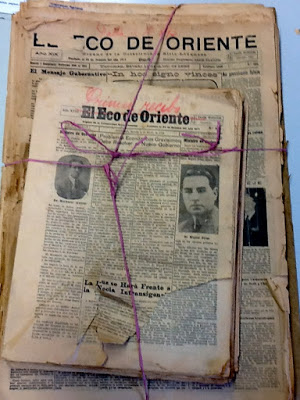

How did Arab-Argentines connect with the rest of the diasporic community? In researching this diaspora community today, some of the most valuable archival sources that we have access to in Argentina consist of Arab-owned newspapers and magazines that date back to the early twentieth century. These periodicals provide us with a window into the networks that Arabic-speaking immigrants formed not only across the far-flung Argentine provinces from Patagonia to the Bolivian border, but also internationally. These primary sources demonstrate that journalists, intellectuals, charity-workers, and industrialists were all concerned with maintaining and fostering relationships between the many different nodes of the Middle Eastern diaspora map. These were highly mobile communities, and many Arab-owned newspapers routinely published sections entitled “Travelers,” or “Arrivals & Departures,” thus informally documenting lists of the comings and goings of community members and families whose travels ranged from inter-provincial to trans-American.

Part of the description of your dissertation mentions “artistic collaboration and exchange.” Can you elaborate on that? Sure! Scholarly studies of Syrian and Lebanese diaspora communities have long acknowledged the importance of famous authors and poets such as Khalil Gibran (1883-1931) and Amin Rihani (1876-1940) in the creation and innovation of distinct forms of diaspora cultural production. Syrians and Lebanese across Latin America read their works in Arabic and in Spanish and Portuguese translation, and contributed their own works to a burgeoning international scene of literary and artistic production. Beyond the genre of the written word, however, there is also a rich history of artists and musicians who played a part in this artistic community. While doing the field work for my own project I encountered records of musical groups, dance troupes, and cinematographers who traveled throughout the Americas, Middle East, and North Africa giving performances and gathering material for their next production. In one case, I unearthed the story of the documentary film project of three young Lebanese men in Argentina. These young artists traveled throughout Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Brazil, and the Levant making documentaries about their Middle Eastern homeland and its diaspora communities in each respective Latin American nation that they visited.

Are there any interesting ways that Arabic speakers assimilated into the South American environment? There were certainly ways in which Arabic speakers combined their own traditions with the cultural panorama that greeted them in Argentina. You mention the dolmas recipe shifting within Lebanese communities in North Carolina – I think that food is a great way to very tangibly track these sorts of exchanges and accommodations. In Argentina, one example of this culinary intermingling is apparent in the case of sfeehas and empanadas. Empanadas are (delicious!) hand-held pies whose basic premise is the same as that of the lamb or beef-filled Lebanese sfeeha. Besides a good steak, I would argue that the empanada is the number one iconic item in traditional Argentine cuisine. A number of restaurants in Argentina that specialize in Lebanese food also offer traditional Argentine beef empanadas which are seasoned differently than the sfeeha. Over the years, the sfeeha has even become so prevalent that most empanada restaurants with a decent selection of flavors also offer “sfijas” – a testament to the compatibility in foodways that this particular dish represents.

What are your favorite places to travel in the world? I definitely enjoy traveling in Argentina because it boasts such a vast and varied landscape. I love being outdoors (when I am not in a dusty archive or sitting at my computer writing!), and the natural beauty of Argentine mountains, glaciers, rainforest, and desert provide endless opportunities for exploring. While on my most recent research trip, I traveled with my partner to the southernmost city in the world: Ushuaia, Argentina. When I wasn’t interviewing local business owners about the history of a prominent Lebanese family who made their home in Ushuaia beginning in 1912, I was able to hike Tierra del Fuego National Park and watch 11pm sunsets over the Beagle Channel. It is one of the most beautiful and remote feeling places that I have ever visited, yet at the same time the landscape reminded me in many ways of the northern Maine coast where I spent many summers as a child growing up in New England.

- Categories: