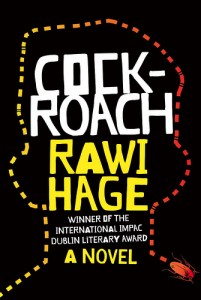

Review of Rawi Hage’s Novel, Cockroach

This article is written by Joseph Geha, professor emeritus at Iowa State University and author of two books; Through and Through: Toledo Stories and Lebanese Blonde. In October 2014, the Center invited Geha to lecture entitled “Is there an Us?” centering on immigration, ethnicity and identity. You can view his lecture here. Geha last reviewed Rabih Alameddine’s An Unnecessary Woman for the Center in December 2014.

The unnamed narrator of Rawi Hage’s widely acclaimed second novel, Cockroach, is a young man from Beirut, trying to make a life in Montreal’s demimonde of Middle Eastern émigrés. Traumatized by war memories, by political cruelty and by guilt over his failure to rescue his sister from an abusive marriage, he is now a stranger in a strange land where the cold he endures is more than weather, “And if you ask why the inhumane temperature, the universe will answer you with tight lips and a cold tone and tell you to go back where you came from if you do not like it here.” His response to the oppressive power of this new universe that “I can neither participate in nor control” is to turn himself into a cockroach. Literally. Rawi Hage, the recipient of numerous literary tributes, including the IMPAC Dublin Award for the best English-Language book published world-wide, is a daring writer. Yes, his narrator, like Gregor Samsa of Kafka’s famous short story, is a human being who metamorphoses into an insect. But here the similarity ends. Poor, tormented Gregor, beset on all sides by the demands of his family, awakened one morning to find that he’d been transformed. Hage’s narrator, on the other hand, changes himself at will; that is, he actually chooses bugdom. And his reason for doing so is at the very heart of this fast paced, exuberant and often darkly funny novel. When we first meet the narrator, he is in a session with his clueless Canadian therapist, Genevieve, as part of court-ordered treatment after a recent suicide attempt. “I will show you who I am,” he tells her, “and it’s not pretty.” As he leaves her office and begins roaming the bitter Montreal streets, we watch him tracking down deadbeat friends, scrounging for a meal, money, a job. We learn that he long ago discovered the power of invisibility and, when the occasion for burglary or voyeurism arises, he can turn himself into a slippery cockroach.

“(S)ix legs appeared from my sides like external ribs, and a newly thick carcass made me oblivious to the splashing water from passing cars. No element of nature could stop me now.”

Not pretty. But not really despicable, either. Because, six legs or no, Hage has given his narrator a heart—and it’s in the right place. He expresses compassion listening to a child crying out as his mother drags him into the house and beats him. He feels love for his girlfriend Shohreh, and later, in his attempts to punish her former torturer, we find ourselves squarely on his side, rooting for him. He can be tricky, true, but since when were narrators always reliable? Like so many hypocrites, he despises hypocrisy and delights in exposing the poser, even himself:

“I want to introduce you to my friend Reza here, I said, playing my part of the existentialist protagonist in a film noir, although I was missing a cigarette and some plumes of smoke.”

For much of Cockroach, the narrator’s day-to-day activities skitter energetically before us like, well, roaches. He busily opens doors, closes doors, walks to a café, walks back, eats, goes to sleep, wakes. Not only does the action keep moving, so too does the language—spinning, pattering, scurrying off on remarkably manic jazz-like riffs, piling metaphors on metaphors, building frantic accumulations of fantastic imagery. Just one example, when the narrator is stalking his therapist:

“She lived in a rich neighbourhood with shop windows displaying expensive clothing and restaurants that echoed with the sounds of expensive utensils, utensils that dug swiftly into livers and ribs and swept sensually above the surface of yellow butter the colour of a September moon, a cold field of hay, the tint of a temple’s stained glass, of brass lamps and altars, of beer jars, wet and full beneath wooden handles that gave me a thirst for an executioner’s hands, for basement doors and the downward swing of falling boats, sailor’s knots, and ropes stretched around gulping, gorging, foaming throats, sounding calls for the last meal, the last count, the last sip before the return of the sun.”

One sentence. Whew. Bicycling the high-wire of a riff (think Rimbaud, think Bob Dylan), it seems that sense becomes subordinate to momentum, to rhythm, to the musical energy of the words themselves. What makes a human being a cockroach? For Gregor Samsa it was his excuse-me-for-living attempts to please his family. For Rawi’s narrator, behind the humor and the poetic flights, the dominant emotion is anger over a dilemma faced not only by the alien, but by the underclass as well, by the disenfranchised, by all who are excluded from the realms of power and taunted to go back where they came from, underground things that must scatter before the light. By the end of the novel the narrator has fulfilled his promise to show us what he is, and indeed the cockroach is not pretty. But the creature itself is strong, enduring, in fact it’s Nature’s ultimate survivor. So too our narrator is oddly powerful in his invisibility, defiant and, at the finish, quite possibly triumphant.

- Categories: