Lebanese in Australia and the politics of whiteness

This article is written by Anne Monsour. She has a PhD in history from the University of Queensland. View her full bio after the article. This article is the second in a three part series. Read the first installment: Uninvited and unwelcome: a brief introduction to early Lebanese migration to Australia.

Perhaps because I had accepted the stereotype of the early Lebanese immigrant as a poor illiterate peasant, or perhaps because of a deliberate silence on the part of the immigrants, I was surprised to find in the documentary sources the early immigrant “voice”, sometimes assertive, often frustrated, at times desperate, but always advocating for equal rights. When people from Syria/Lebanon arrived in the Australian colonies in increasing numbers in the early 1890s, they were immediately described as non-white, identified as non-European, and characterized as undesirable immigrants. Through legislative discrimination, the white Australia policy aimed to cement Australia’s character as a white, Christian society. Classified as Asian, Lebanese faced exclusion from certain industries and occupations; denial of the right to vote or stand for parliament; exclusion from citizenship, restrictions on their ability to hold leases and own property; and disqualification from social services such as the invalid and old-age pensions [1]. Denied the rights readily granted Europeans, they were forced to position themselves within existing racial categories, and from the 1890s lobbied for equal status on the basis that they were white, European and Christian.

In 1893, in the midst of increasing opposition to a perceived “Syrian Invasion,” Abraham Khaled, Chancellor of the Turkish Consulate, claimed the negative allegations resulted from confusing Syrians “with Hindoos and Afghans” and it was unjust to class Syrians as “dirty, cunning, uncivilised thieves or beggars’’. [2] Similarly, Joseph Arida, a Syrian merchant, wrote to the Sydney Morning Herald in defence of Syrians; they were not coloured, but Christian and European, and contrary to the complaints made about them, were generally industrious, hospitable and honest [3]. In 1896, concerned about the implications of the proposed Coloured Races Restriction Bill, a deputation representing Syrians in New South Wales met with the Premier [4] They argued it would be unfair to apply these restrictions to Syrians as they were not coloured but Caucasian, and differed from other Asians because: “We don’t send money away to Asia. We live, work, and spend our money in the colony. We don’t want to go back to a country where despotism reigns supreme. We prefer a civilised and a Christian country, and I think that we should be welcomed.”[5] The premier did not agree. The intention was to exclude “Asiatics” and Syrians were “certainly Asiatics and not Europeans.”[6]

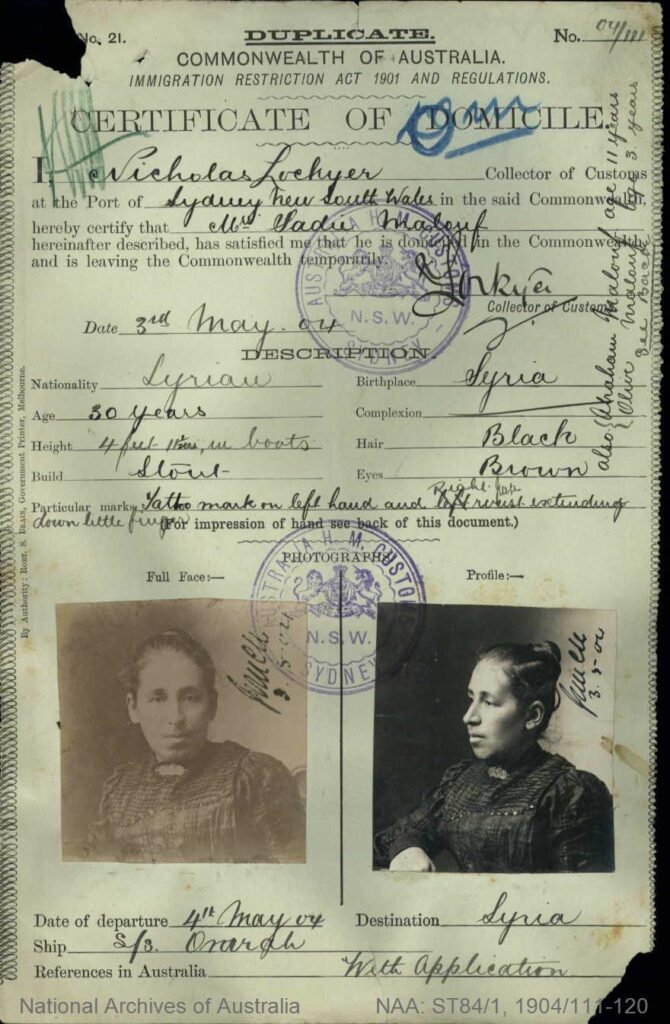

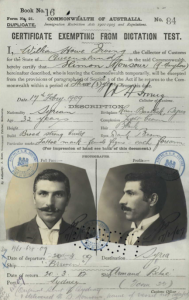

After Federation, the Immigration Restriction Act (1901) limited entry of Lebanese to Australia; the Naturalization Act (1903) excluded all aboriginal natives of Asia from citizenship; and to leave the country temporarily they had to obtain a Certificate of Domicile, later a Certificate of Exemption from the Dictation Test, or they would become prohibited immigrants. As permanent settlers, Lebanese continued to agitate for equal status arguing they should not be included in the same category “as the Chinese, Japanese, Hindoos and other Eastern people”.[7] In 1909, they petitioned the government to allow the restricted admission of Syrians. [8] Arguments put forward in the petition were echoed in letters written by Wadih Abourizk to the Prime Minister and the Minister for External Affairs. [9] According to Abourizk, Syrians were Caucasians whose: “looks, habits, customs, religions, blood, are those of Europeans” and “they should be treated like other white races”. [10] Individual Lebanese also argued to be accepted as European and therefore white. They understood their physical appearance and Christian affiliations were favorable attributes in their bid for citizenship. In 1903, Joseph disputed the correctness of this classification on the basis of his religion: “Although I am termed an Asiatic Alien, I would respectfully point out that I am of the Christian Religion, the same as the rest of the people of Australia.”[11] Another Lebanese immigrant excluded from naturalization because of his birthplace challenged the government’s view he was “…not eligible to become a subject of the King in the ‘Commonwealth’ of Australia on account of being born in Syria. I am a Christian and I think I am eligible to become a subject of the King….”[12] Alf declared he was “not an aboriginal native of Syria but a whit[e] man of good English education”; furthermore, as the term aboriginal referred to “the blackes [sic] and not to the educated residents of a nation or state”, it obviously did not apply to him because he was trilingual(able to write and read English, French and Arabic) and a Christian. [13] Similarly, Samuel refuted the government’s view he was an aboriginal native of Asia: “you quote me as an aboriginal native of Asia. I thought I made it very plain that I was an Assyrian by birth and not a nigger”. [14] The term “aboriginal native” was being used by the government to distinguish between Europeans and non-Europeans. These two individuals were clearly reacting to the indelible line which had been drawn separating superior Europeans from inferior “others” and positioning themselves on the white side of the colour line.

As Lebanese were disqualified from naturalization between 1904 and 1920, all applications in this period should have been unsuccessful. However, a significant number successfully circumvented the restrictions by claiming a European birthplace. The official records show this was deliberate and based on an understanding of the legislation. Joseph, who applied unsuccessfully in 1907 as “a native of Syria, Mount Lebanon”, re-applied five months later, stating his birthplace as Constantinople, Turkey [15]. Similarly, Jacob, refused naturalization as an “Assyrian” in 1903, applied successfully claiming a Greek birthplace [16]. Between 1904 and 1920, out of a sample of 123 naturalization applications by Lebanese immigrants between 1904 and 1920, approximately 53 per cent claimed to be born in Europe. Birthplace was obviously the key to the success or failure of the application. All applicants born in Syria or Mount Lebanon were rejected, while those who claimed a European birthplace were successful. At face value, claiming a false birthplace is clearly dishonest. However, this action can also be interpreted as a desperate measure on the part of people whom the evidence clearly indicates were law-abiding, to overcome an unjust law.

By the 1920s, at the legislative and executive levels, Lebanese immigrants had gained some concessions; however, their acceptance was limited and tenuous. It was easier to become naturalized but naturalized Lebanese were excluded from the franchise until 1925, and were only granted pension rights in 1941. The struggle for equal rights extracted a high price. The immigrants knew in a very practical sense the key to acceptability was being accepted as white, European and Christian. Not surprising then, that they did not tell their children about their experiences as outsiders; that they assimilated into mainstream churches; insisted their children only speak English; and passed on little information about their Lebanese heritage. In their bid for acceptance, the early immigrants acted to ‘white out’ their differences and in the process became virtually invisible.

References

[1] “Disabilities of Aliens and Coloured Persons within the Commonwealth and its Territories”,(1920), Prime Minister’s Department, A1/1, 21/13034, National Archives of Australia( NAA.), Australian Capital Territory (ACT); `List Showing Restrictions or Disabilities in Queensland Applicable to Aliens’,(1943), A/7513, 1234/43, Queensland State Archives,(QSA).

[2] Evening News (Sydney), 3 February 1893, 7.

[3] Sydney Morning Herald (SMH), 27 February 1893, 8.

[4] SMH, 23 October 1896, 3.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Argus (Melbourne), 20 October 1896, 5.

[7] Chief Clerk, Department of External Affairs, Memorandum, 20363, 27 October 1914, A1/1, 14/20363, NAA ACT).

[8] Department of External Affairs, Memorandum, 10/1092, 16 March 1910, A1/1, 10/3915, NAA (ACT).

[9] Wadih Abourizk to Alfred Deakin, 09/5456, 10 January 1910 & Wadih Abourizk to Egerton Batchelor, 10/1092, 7 June 1910, A1/1, 10/3915, NAA (ACT).

[10] Wadih Abourizk to Alfred Deakin, 09/5456, 10 January 1910.

[11] Joseph A. to Home Secretary, 7760, 9 June 1903, Col/74(a), QSA.

[12] Joseph M. to Department of External Affairs, A1/1, 07/4778, NAA (ACT).

[13] Alf M. to Atlee Hunt, 04/6496, 17 August 1904, A1/1, 04/6496, NAA (ACT).

[14] Samual M. to Secretary, Home & Territories Department, 19/18793, 5 January 1920, A1/1, 21/25706, NAA (ACT).

[15] Joseph A. to Minister, Department of External Affairs, 07/569, 9 January 1907, A1/1, 09/675, NAA (ACT); Secretary, Department of External Affairs to Joseph A., 07/569, 21 January 1907; Joseph A. Statutory Declaration, 29 June 1907.

[16] Jacob A., Memorial, 14 January 1903, 3802/1903, Col/73(a), QSA; Jacob A., Naturalization Application, A1/1, 05/1506, NAA (ACT).

Short bio

This article is written by Anne Monsour. She has a PhD in history from the University of Queensland. Her thesis, ‘Negotiating a Place in a White Australia’, is a study of the settlement of Lebanese in Australia from the 1880s to 1947. For almost two decades, Anne has been researching, writing and speaking (in academic and community forums in Australia and overseas) about the history of Lebanese settlement in Australia. She is the author of Not Quite White: Lebanese and the White Australia Policy 1880 to 1947 (Post Pressed, 2010), and has edited two books about Lebanese in Queensland: Raw Kibbeh: Generations of Lebanese Enterprise (2009) and Here to Stay: Lebanese in Toowoomba and South West Queensland (2012). Anne now works as a Professional Historian. Born in Biggenden, Queensland where her father was a general storekeeper, Anne is the daughter of Lebanese immigrants from Rass Baalbec. You can read a review of Monsour’s 2010 work at Mashriq and Mahjar, Volume I, Issue 2, Fall/Winter 2013.

- Categories: