Lest we forget: Australian Lebanese and the Great War (1914-1918)

This article is written by Anne Monsour. She has a PhD in history from the University of Queensland. This article is the third and final installment in her series. Read the first installment: Uninvited and unwelcome: a brief introduction to early Lebanese migration to Australia and the second installment: Lebanese in Australia and the Politics of Whiteness.

The Anzac Centenary (2014-2018) marks 100 years since Australia’s involvement in the First World War, an experience characterized as “a milestone of special significance to all Australians” that “helped define us as people and as a nation.”[2] Its official website reveals both the breadth and the gravitas of the Anzac Centenary Program commemorating “more than a century of service by Australian servicemen and women.” PhD candidate, Geraldine Khachan’s research has located almost 400 Australian-Lebanese who served in the world wars.[3] Yet despite their evident support of the Australian war effort, for many Lebanese families in Australia, the First World War exacerbated their experience as outsiders and reminded them their acceptance was tenuous. At the advent of the First World War, many Lebanese had lived in Australia for more than thirty years. Despite facing extensive, racially based legislative discrimination, these immigrants had determined to make Australia their home. They established businesses, raised families and became active participants in their local communities. Years of lobbying had succeeded in gaining exemptions from some of the restrictions imposed on Asians, and achieving equal status seemed closer when in 1911, the Minister for External Affairs, Egerton Batchelor, made public his view that Syrians in Australia should be granted access to citizenship.[4] However, these hopes were dashed when, in October 1914, the Commonwealth Parliament passed the War Precautions Act. As Turkish subjects, Lebanese were declared enemy aliens and placed under surveillance; additionally, the entry of relatives or friends, a concession granted to Syrians in relation to the Immigration Restriction Act (1901), was disallowed.[5]

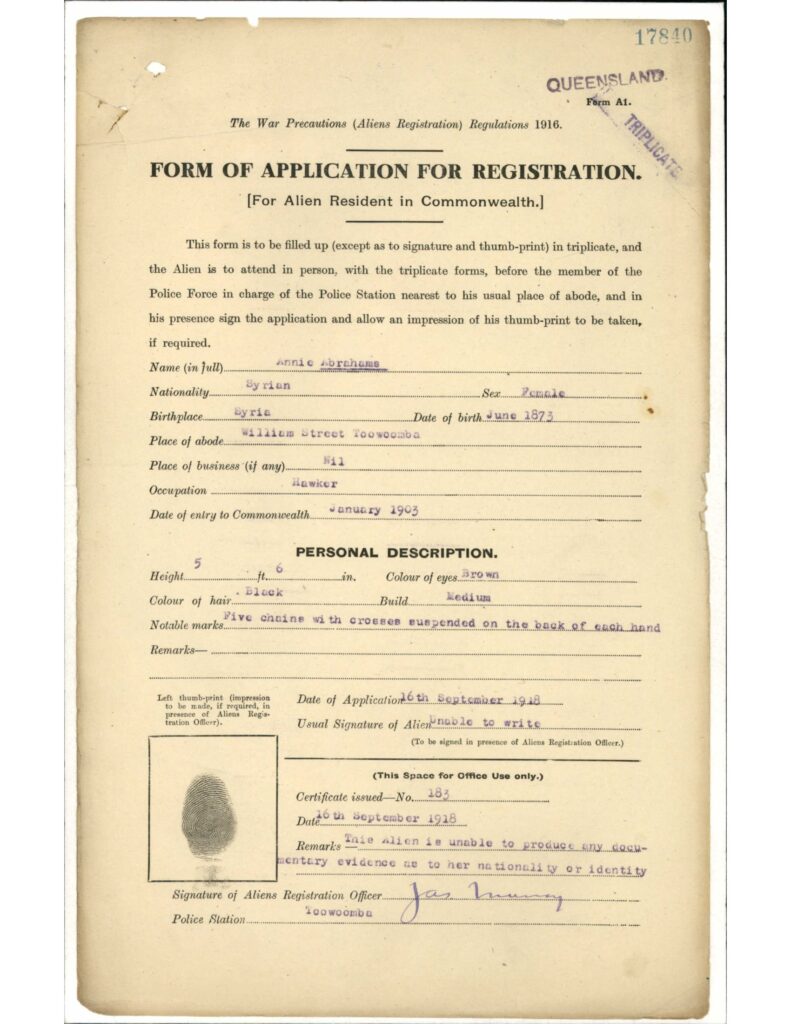

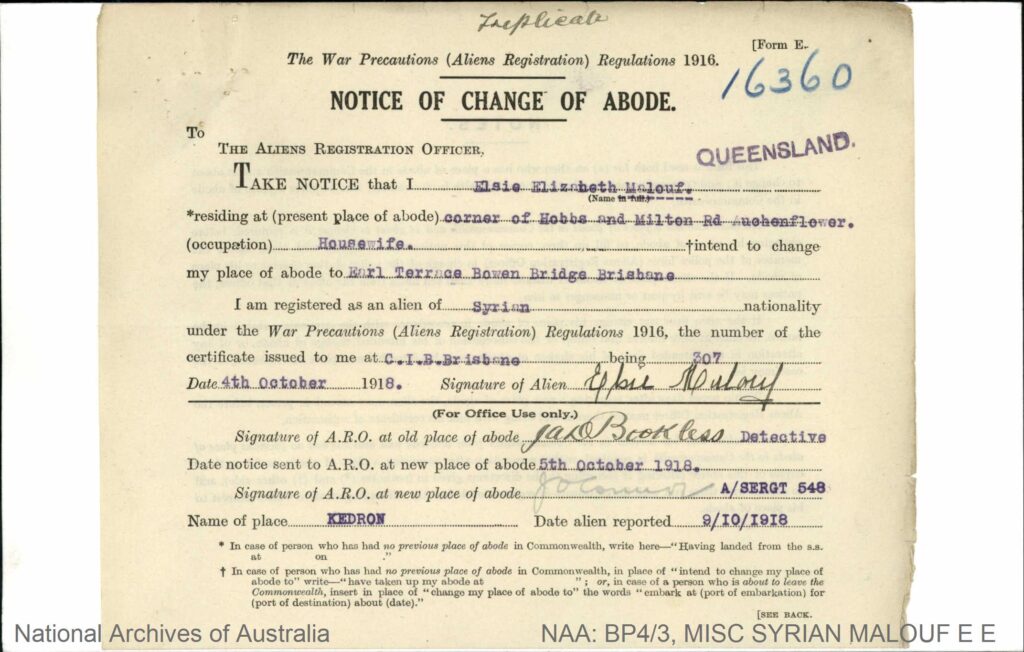

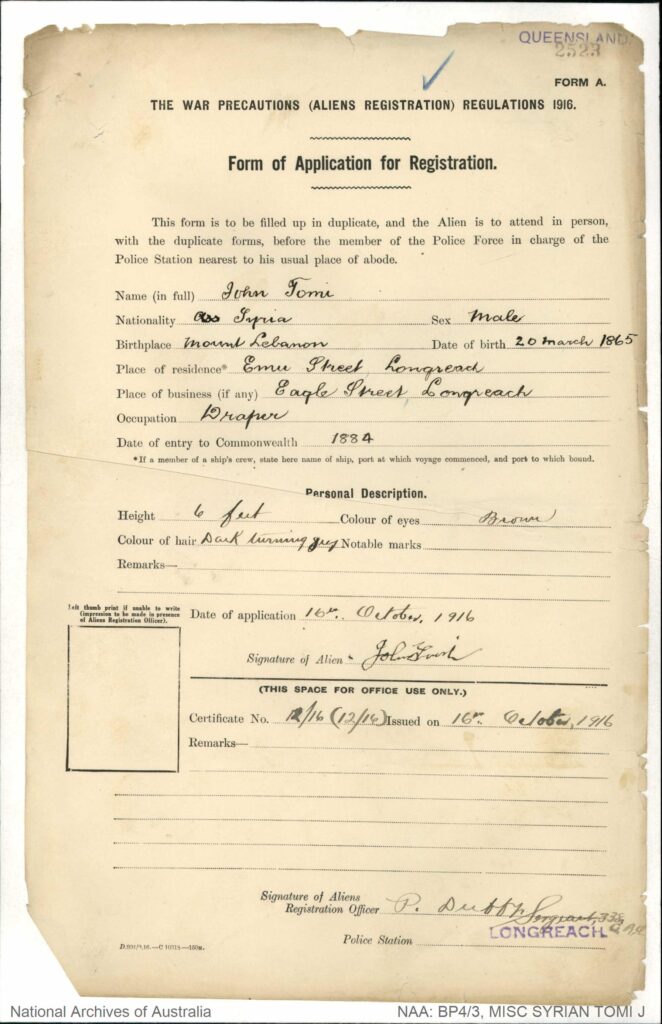

Enemy alien status must have been galling for the many Lebanese who had repeatedly been denied access to citizenship as ‘aboriginal natives of Asia’; however, worse was to come. In May 1916, the definition of an enemy subject was extended to include naturalized residents as well as “any Australian natural-born subject whose father or grandfather was a subject of a country at war with the King”.[6] Now, even their Australian-born children were required to register at the local police station and to notify the police if they were leaving town or changing their address. All Australian-born wives were also required to register as aliens.[7] Ironically, many Lebanese had children or siblings serving in the Australian Imperial Forces some of whom had already given their lives in the service of their nation. Trooper Joseph Betro, for example, who died in October 1915, was one of three brothers who had enlisted to fight. [8] Being under scrutiny was not a new experience for these immigrants, but this was an added and damaging intrusion into their everyday lives. For some, such as John Nader, George Ellis and Antony Abdullah, enemy alien status threatened their livelihood as hawkers because the authorities were reluctant to renew their licenses despite depositions regarding their lengthy residence, good character, loyalty and Christian faith.[9] The seriousness of their changed status was confirmed for Lebanese by the internment of Nicholas William Malouf in 1917, and reinforced when others were charged with breaching War Precautions regulations. [10] Joseph Mansour Fakhrey, a travelling optician, came to Australia as a one year old; now an enemy alien, he was charged with being in possession of a motor vehicle without the written permission of the senior police officer in his local area.[11] In 1918, Annie Abrahams and Maroon Beetres, both long-term residents working as hawkers in the same district, were fined for breaching Regulation 5 (1) of the War Precautions Aliens Registration Regulations of 1916.[12]

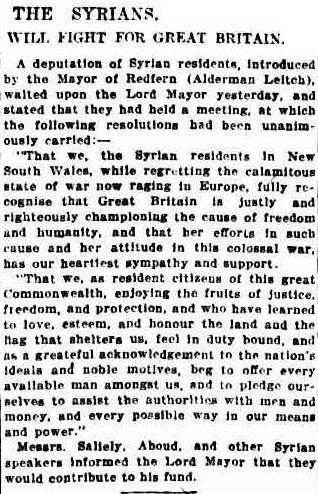

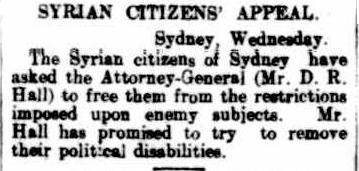

Lebanese believed their official status as Turkish subjects obscured their opposition to the Turkish occupation of Lebanon and to the fact they strongly supported the allied cause. Throughout the war, they opposed their status as enemy aliens and representatives of the community lobbied strongly to have their position better understood. In August 1914, a deputation of Syrian residents presented the Lord Mayor of Sydney with a declaration of loyalty to Great Britain and pledged “to assist the authorities with men and money, and every possible way in our means and power.”[13] Another Syrian deputation met with the Assistant Minister for External Affairs and the Minister for Defence in November 1914 to explain they were from Mount Lebanon and only Turkish subjects by compulsion.[14] Others wrote to the newspapers explaining the Syrian position and declaring their loyalty to the British Crown and appreciation of the British way of life.[15] Syrians gave generously to patriotic funds and to the Red Cross and this was noted in their collective favour as early as 1915:

It may be mentioned that the Syrian community of Melbourne has during the recent war crisis shown considerable public spiritedness, some of the younger Australian born members of the community having joined the expeditionary forces while others have contributed large sums towards the relief funds.[16]

The Commonwealth Government did understand that Greek, Armenian and Syrians though technically Turkish subjects were likely to be opposed to the Turkish regime and as a result, those who were Christian could request exemption from certain requirements of the law applying to alien enemies.[17] However, this understanding and the consequent exemptions were not effectively communicated to the immigrants or to the general public. Whether Lebanese were informed of their special status was dependent on the attitude of the District Commandant at whose discretion the exemptions were to be granted, and on the attitude of the local police who were responsible for implementing the legislation. It was, of course, also the role of the police to keep all Turkish subjects under surveillance.

For the German-Australian community, who, until the First World War, had been favoured immigrants, their transformation from “citizens with full civil rights to outcasts” was alarming.[18] In contrast, Lebanese immigrants had never been granted full citizenship status and their treatment during the war simply reinforced what they already knew. Their acceptability as immigrants and citizens was both conditional and tenuous. A lesson still relevant, one hundred years later, as Australian Lebanese/Arabs/people of Middle Eastern appearance, partly due to racism, anti-Muslim sentiments and the ongoing “War on Terror”, are once more under scrutiny and facing questions about their loyalty and desirability.[19]

References

[1] (In reference to the title: “Lest we Forget”) These words from the poem “Recessional” by Rudyard Kipling (1897) are often added to the “Ode of Remembrance” recited at memorial services commemorating the First World War, such as ANZAC Day.

[2] Australian Government, “100 Years of ANZAC: the Spirit Lives 2014-2018 “, http://www.anzaccentenary.gov.au/ (Accessed 30 May 2015).

[3] Geraldine Khachan conversation with Anne Monsour, 31 May 2015. Geraldine is a PhD candidate in Sociology at the Australian National University, Canberra. Her research topic is titled: War, Diasporas & Assimilation: Responses from Lebanese Migration.

[4] Until the 1940s, Lebanese in Australia were called Syrians. Egerton Batchelor to General Secretary, Australian Natives’ Association, Perth, 14/20363, 4 January 1911, A1/1, 14/20363, NAA (ACT).

[5] Major Wallace Brown to Commissioner of Police, Brisbane, November 1914, 1268.M.38, A/11954, QSA; Atlee Hunt, Department of External Affairs, Memorandum, 14/20363, 2 November 1914, A1/1, 14/20363, NAA (ACT).

[6] Gerhard Fischer, Enemy Aliens: Internment and the Homefront Experience in Australia 1914-1920, (St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1989), p. 75.

[7] Elsie Malouf, Form of Application for Registration, 16360, 7 June 1918, BP4/3, Syria, NAA (Qld).

[8] Barrier Miner (Broken Hill, NSW), 19 December 1915, p. 2; Advertiser (Adelaide, SA), 14 December 1915, p. 8.

[9] Wodonga and Towong Sentinel (Victoria), 18 December 1914, p. 2; Shoalhaven News and South Coast Districts Advertiser (NSW), 9 December 1916, p. 4.

[10] Acting Sergeant, Gatton Station to Inspector of Police, Toowoomba, 1527, 28 June 1917, BP4/1, 66/4/1256, NAA (Qld).

[11] Bendigo Advertiser (Victoria), 6 August 1918, p. 3.

[12] Annie Abrahams, Conviction of Alien Who Is Registered under “The War Precautions (Alien Registration) Regulation 1916”, 17840, 28 September 1918, BP4/3, Syria, NAA (Qld); Maroon Beetres, Conviction of Alien Who Is Registered under “The War Precautions (Alien Registration) Regulation 1916”, 18546, 13 January 1919, BP4/3, Syria, NAA (Qld).

[13] Sydney Morning Herald (NSW), 14 August 1914, p. 10.

[14] Sydney Morning Herald, 10 November 1914, p. 8.

[15] For example: Omeo Standard and Mining Gazette (Victoria), 9 March 1915, p. 4; Albury Banner and Wodonga Express (NSW) 24 September 1915, p. 46; Tamworth Daily Observer (NSW), 11 September 1915, p. 2.

[16] Department of External Affairs, ‘Commonwealth Naturalization: Inclusion of Syrians’, 03100, 10 February 1915, A6006/1, 3rd Fisher Sept 14–Oct 15, NAA (ACT).

[17] Atlee Hunt, Department of External Affairs, 1 March 1916, A1/1, 21/11220, NAA (ACT); Major Wallace Brown, Commonwealth Military Services to Commissioner of Police, Brisbane, 22 January 1915, 1268.M.38, A/11954, QSA.

[18] Fischer, Enemy Aliens, p. 66.

[19] See: Abood, P. (2005). ‘Unpacking Racism’. Community Forum on Racism, 12 May, University of Newcastle, Australia; Collins, J., Noble, G., Poynting, S. & Tabar, P. (2000).

[20] Kebabs, Kids, Cops & Crime: Youth, Ethnicity and Crime. Sydney: Pluto Press; Hage, G., ed. (2002).

[21] Arab Australians Today: Citizenship and Belonging . South Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press; Hyndman-Rizik, N. (2008).

[22] “Shrinking World’: Cronulla, Anti-Lebanese Racism and Return Visits in the Sydney Hadchiti Lebanese Community’. Anthropological Forum, 18:1, 37-55; Poynting, S., Noble, G., Tabar, P., & Collins, J. (2004). Bin Laden in the Suburbs: Criminalising the Arab Other. Sydney: Federation Press.

Images

Figure 1: Sydney Morning Herald (NSW), 14 August 1914, p. 10 (accessed 2 June 2015), http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15529607

Figure 2: NAA: BP4/3, MISC SYRIAN ABRAHAMS A, “Abrahams, Annie – Nationality: Syrian [Miscellaneous] – Alien Registration Certificate No 183 issued 16 September 1918 at Toowoomba.”

Figure 3: NAA: BP4/3, MISC SYRIAN MALOUF E E, “Malouf, Elsie Elizabeth – Nationality: Syrian [Miscellaneous] – Alien Registration Certificate No 307 issued 7 June 1918 at Brisbane.”

Figure 4: Barrier Miner ( NSW), 6 September 1916, p. 2, (Accessed 2 June 2015), http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article45431777

Figure 5: NAA: BP4/3, MISC SYRIAN TOMI J, “Tomi, John – Nationality: Syrian [Miscellaneous] – Alien Registration Certificate No 12/16 issued 16 October 1916 at Longreach.”

Short bio

Anne Monsour has a PhD in history from the University of Queensland. Her thesis, ‘Negotiating a Place in a White Australia’, is a study of the settlement of Lebanese in Australia from the 1880s to 1947. For almost two decades, Anne has been researching, writing and speaking (in academic and community forums in Australia and overseas) about the history of Lebanese settlement in Australia. She is the author of Not Quite White: Lebanese and the White Australia Policy 1880 to 1947 (Post Pressed, 2010), and has edited two books about Lebanese in Queensland: Raw Kibbeh: Generations of Lebanese Enterprise (2009) and Here to Stay: Lebanese in Toowoomba and South West Queensland (2012). Anne now works as a Professional Historian. Born in Biggenden, Queensland where her father was a general storekeeper, Anne is the daughter of Lebanese immigrants from Rass Baalbec. You can read a review of Monsour’s 2010 work at Mashriq and Mahjar, Volume I, Issue 2, Fall/Winter 2013.

- Categories: