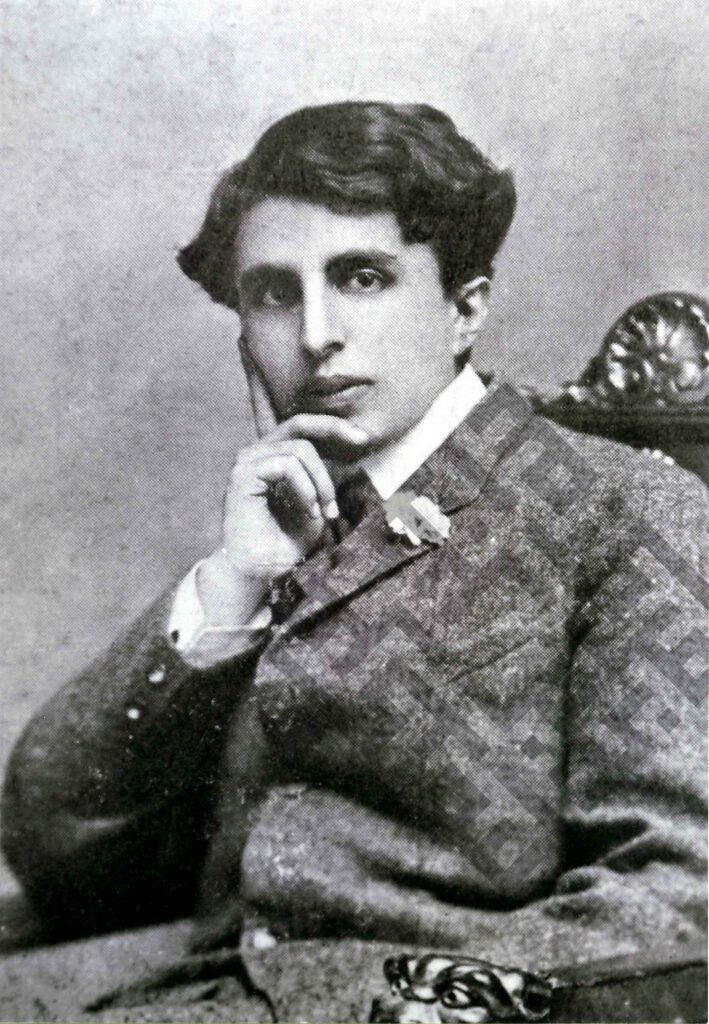

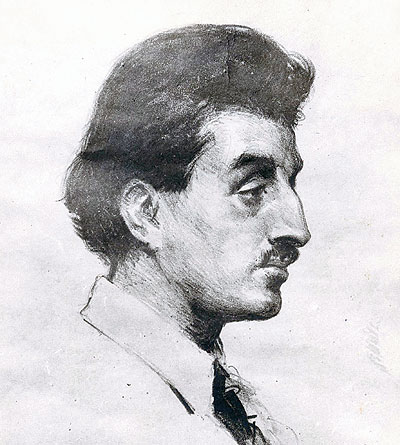

Ameen Rihani, Lebanese Activist for Palestine

Jacob Norris is Lecturer in Middle Eastern History at the University of Sussex in Brighton, UK. He completed his PhD at the University of Cambridge in 2010. His book, Land of Progress: Palestine in the Age of Colonial Development, 1905-1948, was published by Oxford University Press in 2013. His current research focuses on the town of Bethlehem and the global migrations of its residents in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Ameen Rihani (1876-1940) stands as a towering intellectual figure in the history of the Lebanese diaspora. He was the first author truly to bridge the worlds of Arabic and English literature. Writing in both languages, he penned dozens of novels as well as countless poems, essays and treatises. Included among these was The Book of Khalid, widely celebrated as the first Arab-American novel written in English. Alongside his literary achievements, there is another, less well known aspect of his career: Rihani the political activist. As a champion of liberal, progressive values, he adopted a variety of causes, from women’s rights to religious freedom. But there was one issue that occupied him more than any other: the Palestine question. What did this most original of thinkers have to say about Palestine and how might it still be relevant a century later? From as early as 1917, Rihani recognized the importance of the Palestine issue, and how it would reverberate around the world. The outbreak of violence in Palestine in 1929 greatly intensified his activism. For the next decade he devoted great energy to promoting the Arab Palestinian cause, particularly among the American public. He published numerous articles, debated leading American Zionists, and lobbied senior senators and congressmen. He warned of the dangers of Jewish colonization in Palestine at a time when the American Zionist lobby was first gaining strength. As a self-styled intermediary between American and Arab cultural values, his activism takes us back to a time when a very different type of American engagement with the Middle East still seemed possible. His commitment to the Palestinian cause partly stemmed from his respect for the area’s religious significance. Although he was often a sharp critic of religious institutions, Rihani was a deeply spiritual man and held Palestine’s sanctity in high regard.

The Book of Khalid famously satirizes the early Lebanese and Palestinian immigrants in New York who sold fake Holy Land trinkets to “unsuspecting housewives”. The holiness of the Holy Land was a serious matter for Rihani. But to properly understand his engagement with Palestine we must also revisit the politics of nationalism in the early 20th-century Middle East. Rihani is today celebrated as a literary hero of a specifically Lebanese diaspora, but he himself considered his national identity to be Syrian. In the years leading up to and immediately following World War I, most intellectuals in the region considered Palestine, as well as Lebanon, to be part of this “historic Syria” or bilad al-sham. In his early writings on the Palestine question Rihani was thus writing about an area he held to be part of his own homeland. His first serious article on the subject, published in the New York literary magazine The Bookman in 1917, demonstrates this clearly. Written shortly before the British government issued the Balfour Declaration, the article takes us back to a time when the Zionist aim of creating a Jewish national homeland in Palestine still appeared a distant dream. In his eyes the inhabitants of Palestine were unequivocally “Syrian”, an identity that incorporated all the area’s religious groups. His article rejected any form of foreign rule, including by European powers that he knew were coveting Palestine in their post-war plans. Instead he advocated a benign leader who would govern Palestine “in the name of the people of the country, of the natives themselves—the Syrian Christians, the Syrian Mohammedans and the Syrian Jews.” Interestingly Rihani viewed the Syrian nation as distinct from a wider Arab identity. While he acknowledged the Arabic language as central to Syrian cultural life, he held onto a narrower definition of “Arab” that was linked to the tribal communities that had exported Islam out of the Arabian Desert.

In the aftermath of World War I, he believed the newly independent Arab kingdom in the Hejaz should not be allowed to extend its rule into Palestine, “until they prove themselves capable of establishing and maintaining a liberal government.” It was, then, a more distinctly Syrian brand of nationalism that fired Rihani’s early interventions on Palestine. From today’s vantage point we might associate nationalism with aggressive and chauvinistic values. But for Rihani it carried very different connotations. He saw nationalist politics as a means of overcoming what he viewed as the debilitating effects of religious sectarianism. Nationalism in his eyes was a liberating, progressive force that would set the region on the course to prosperity and enlightenment. In 1917 he had no doubt that the Syrian national movement embodied these values: “the Syrians of to-day…aspire to something higher than sectarianism, are abandoning religion as a political issue and would, in a word, develop a national spirit even at the expense of religion.” The possibility of Palestine forming the southern part of a future Syrian nation-state quickly ebbed away after 1917, but Rihani continued to lobby for the Palestinian case. As the emphasis switched from a Syrian to an Arab Palestinian struggle, he remained convinced that secular nationalism was the only way to overcome “religious fanaticism” in Palestine. He opposed Zionism on these grounds, considering it to be a religious movement based on Jewish orthodoxy that would take Palestine backwards towards sectarian conflict. Underlying all his writing on the subject was an unflinching belief in progress: the idea that society was steadily improving on a linear path towards a more enlightened, and ultimately secular, future. In this belief he was in line with his contemporaries in the Arabic nahda – the cultural renaissance that strove to modernize Arabic language, literature and thought in the 19th century. Much is made of Rihani’s absorption of western literary styles, especially romanticism and the work of American transcendentalists like Ralph Emerson and Walt Whitman. But we must also place him within intellectual trends sweeping the Eastern Mediterranean during his lifetime – a truly cosmopolitan thinker who absorbed influences wherever he went. Many would contest Rihani’s view of Zionism as a movement of religious orthodoxy. But there is no doubting the division the movement opened up in Palestine between Jews and non-Jews.

Rihani’s confidence in the inevitability of secular modernization has proved unfounded in the Middle East. He would barely recognize the region today with its all pervasive religious politics. Perhaps more than anywhere else, historic Palestine has been torn apart by the politics of religious identity, with Arab Palestinians still counting the cost. In this sense Rihani’s words still speak to us. Many people involved in Palestinian activism are now returning to the idea of “one democratic state” in historic Palestine. The two-state solution, they argue, has not only become unworkable, it is based on the politics of sectarian division rather than universal values like tolerance, justice and inclusivity. In this context Rihani’s words ring true for a new generation of Palestinian activists. Palestine, he wrote, “should remain one and indivisible… and let us hope it will enjoy the blessings of a liberal and just government where everyone, Christian, Mohammedan and Jew, will share equally the same rights, religious and political, and the same equality of freedom and protection.”

Sources

Ameen Rihani, The Fate of Palestine: A Series of Lectures, Articles, and Documents about the Palestinian Problem and Zionism (Rihani Print. and Pub. House, 1967)

Lawrence Davidson, America’s Palestine: Popular and Official Perceptions from Balfour to Israeli Statehood (University Press of Florida, 2001)

Hani Bawardi, The Making of Arab Americans: From Syrian Nationalism to U.S. Citizenship (University of Texas Press, 2014)

- Categories: