Mary Mills (1912-2010): African-American Nurse in Lebanon

This article is co-written by Micah Khater and Graham Auman Pitts. Khater is a graduate (’15) of North Carolina State University with a B.A. in History and French. Originally from North Carolina, Pitts completed his dissertation in Georgetown University’s History department on the environmental history of Lebanon.

In all likelihood only one individual has been awarded both Lebanon’s Order of the Cedar and North Carolina’s Order of the Longleaf Pine. Mary (Margaret) Lee Mills, at first glance, may seem like an unlikely candidate for that distinction. Born in rural Pender County, North Carolina in August 1912, Mills hailed from the disenfranchised African-American community of one of the poorest parts of NC. How did she come to travel to Lebanon, much less win the highest award bestowed by the Lebanese government? As a young girl, Mary Lee Mills wanted to “go into something that [would] pay…some money” as a route to a better life. She was one of eleven children. Hard times, including adverse weather conditions, had forced many African Americans to migrate north in the 1910s and 1920s. But Mills and her family remained in Pender County, North Carolina where her father worked as a farm laborer. With economic stability in mind, Mills charted out her future at an early age. She first considered studying law, but “saw so many hungry lawyers.” Mills settled on nursing after reading a letter that suggested that the profession would provide “income to help [her] do whatever else [she] wanted.”[1]

Mills’ grandparents, enslaved and then emancipated, had lived through the hopeful but brief period of Reconstruction. White North Carolina Democrats, displeased with growing African-American political participation, began a brutal white supremacy campaign culminating in the violent coup d’état in 1898 in Wilmington, just thirty miles from Watha where Mills’ family settled. White mobs lynched as many as sixty black men, attacked the state’s only black newspaper, and deposed the elected government –which included African-Americans- in a bid to extinguish the political influence of the black community.[2] Raised in the aftermath of the turmoil, Mills faced myriad challenges, particularly with regard to education. Despite the Rosenwald Fund’s construction of schools for black children, rural African American students struggled to transcend systemic inequalities.[3] Because of her determination to seek educational opportunities, Mills was able to leave Pender County. At age 18, she moved to Durham to study nursing at Lincoln Hospital[4] where she encountered an entirely different social milieu, including that which she hoped to become—an urban middle class woman.[5]

Surrounded by economic prosperity and higher education, Mills must have felt that she had come far from her impoverished life in Pender County. She had not escaped the persistent reality of racial inequality, however. Later, she would recall that while working as a midwife in Roxboro, where she helped a woman birth premature triplets, she had to drive the mother and her babies more than an hour back to Durham to the hospital for African-Americans. No hospital in Person County would accept them.[6] After a sojourn in New York City, where she studied at New York University and a midwifery school, Mills returned to North Carolina to establish a nursing school at North Carolina College as the segregated counterpart to UNC-Chapel Hill. In 1946, “Happily settled in a teaching assignment […] planning for the next year,” she received an offer for a tour of duty in Liberia from the U.S. Public Health Service. She had rejected two previous offers, but was ultimately swayed by the promise of travel. [7]

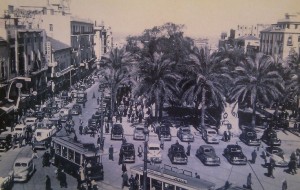

After four years overseeing an inoculation program in Liberia, Mills travelled to Lebanon in 1951 to help launch the country’s nursing education program. She felt welcome in the new environment: “The Lebanese people were not strange to me,” she wrote, “I had acquaintances in other parts of the worlds whose relatives still resided there […] it was only fitting that I received the grand welcoming party so typical of Lebanese hospitality.” “For the first two to three months” she lived with an “Arab family,” Although she would never claim to be fluent in Arabic, she used colloquial phrases in informal situations, answering inquiries about her status as a single woman with a joking “Arabic proverb”: “Ma fii fluse, ma fii aruse [No money, no bride].”[8] Mills would later work in Cambodia and Vietnam as an officer in the U.S. Public Health Service.

Why would she, coming from a community so in need of public health and nurses -in the 1950s as now- travel to pursue public health initiatives in far-flung countries rather than remaining in North Carolina? As with many African American women in the mid-twentieth century, education expanded Mills’ opportunities for self-expression and autonomy. Travel reinforced these newfound “freedoms”: freedom to make a living, to reinvent herself, and to have leisure time (something undoubtedly rare during her childhood on the farm). Furthermore, whereas North Carolina’s classrooms and lunch counters had not been integrated by the early 1950s, many foreign countries offered public spaces free from legal segregation.

Viewed through a broader lens, Mills’ story provides insight into the evolving relationship between Lebanon and the United States. Lebanon was in a unique position, among recently decolonized countries, to assimilate the new public health regime sponsored by U.S. global development projects, such as the Point Four program [9] that brought Mills to the country. Lebanon had nearly as many doctors per-capita as France.[10] In addition to the high levels of medical education among the populace, the Lebanese, many of whom had traveled and lived abroad, felt at ease with foreigners, and knew how to take advantage of U.S. technical assistance in the medical field.[11] While in Lebanon, Mills worked at Point Four’s model clinic in Chtoura, teaching nursing and helping to combat treatable diseases, like trachoma, which plagued the rural population. Along with the Rockefeller, Ford, and Near East Foundations, U.S. government projects contributed decisively to improving public health in Lebanon. Mills remained in the country until 1957, when she took new assignments in Southeast Asia. Evidently appreciative of her contribution to the well-being of the Lebanese people, the government awarded her the Order of the Cedar before she left. Education and travel enabled Mills to escape from poverty and expand her possibilities as an individual. Much like Mills, many Lebanese migrants had their own formative experiences while traveling in the late nineteenth century. While many Lebanese left the shores of the Eastern Mediterranean in search of a better life, many ultimately returned home, bringing with them new ideas. Through these avenues of transnational exchange, the Lebanese constructively adapted the U.S. public health system to fit their own needs in the 1950s. The unlikely conjuncture of Mills’ life with Lebanon’s history is a testament to the value of travel/migration and education as a force for personal and collective empowerment.

Sources

[1] “Mary Mills Transcript for Centennial Video,” North Carolina Nursing History: Appalachian State University, http://nursinghistory.appstate.edu/mary-mills-transcript-centennial-video (accessed August 10, 2015).

[2] Glenda Gilmore, Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1896-1920 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1996), xv-xxii.

[3] James D. Anderson, The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1988), 152. The Julius Rosenwald Fund, established in 1917, reflected the special interest that northern philanthropists took in black education in the South. During the first half of the twentieth century, rural black communities throughout the South petitioned the Fund to help supplement community fundraising. While schools built in collaboration with the fund bore the name “Rosenwald,” the buildings were often constructed with only a small percentage of assistance from the Rosenwald Fund.

[4] Ben Steelman, “Higher Cause,” Star News, February 22, 1998.

[5] Leslie Brown, Upbuilding Black Durham: Gender, Class, and Black Community Development in the Jim Crow South (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 162-163; “Social Gathering,” The Carolina Times, September 2, 1939 and Hill’s Durham (Durham County, N.C.) City Directory (1935), United States Library of Congress Archive, http://library.digitalnc.org/cdm/ref/collection/dirdurham/id/20336 (accessed August 11, 2015).

[6] Ben Steelman, “Life of Service for Pender County Nurse Crossed Seas,” Star News, 5 February 2010.

[7] Rockefeller Foundation Archives (Sleepy Hollow, NY), F. Rockefeller Foundation records, general correspondence, RG 2, 1958-1970. Subgroup 1962: General Correspondence; Series 02.1. Reel 18. Mary Mills, “Commemorative Epistle Honoring My Mom on the Occasion of Her Birthday,” 17 October 1962.

[8] RF, General Correspondence, RG 2, 1958-1970. Subgroup 1962: General Correspondence; Series 02.1. Reel 18. Mary Mills, “Commemorative Epistle Honoring My Mom on the Occasion of Her Birthday,” 17 October 1962.

[9] Point Four later became U.S. AID.

[10] According to the U.N. Statistical Yearbook from 1956. Lebanon’s 1,200 inhabitants per physician dwarfed Egypt’s 3,500 and Jordan’s 7,400. Lebanon’s situation was also favorable compared with countries, which had never been colonized. Mexico had half as many doctors per inhabitant at 2,400 while Turkey possessed 3,400.

[11] English as commonly spoken in Beirut as elsewhere, and American technicians like Mills were thus doubly effective in liaising with Lebanese colleagues to spread novel techniques and technologies. In turn, Lebanon fought relatively quick campaigns to eradicate epidemic diseases, such as malaria.

- Categories: