“The Many Labors of Progress”: Digitally Mapping the Arab-Argentine Community

This blog post is co-authored by Dr. Lily Balloffet, current Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Khayrallah Center, and Darby Hehl, Spanish Language & Education Major (class of 2019) at NC State. Darby became involved with the Khayrallah Center after taking a Latin American History course with Dr. Balloffet in Fall 2015. Dr. Balloffet spent the past year at the Khayrallah Center, where she was on the editorial board for Mashriq & Mahjar: Journal of Middle East Migration Studies. She will continue her research and teaching this coming Fall in the History Department at Western Carolina University.

Introduction

The Argentine physical landscape represents the most diverse South American terrain that people traversed during the nineteenth through early twentieth century immigration “boom.” It ranges from tropical rainforest in the northeast, to the high deserts of the northwest, through central grassy pampas and rolling hills, and into craggy Patagonian terrain rutted by ancient glacial flows. Despite this extremely varied terrain, immigrants fanned out across Argentina beginning in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. They made homes, and established communities, businesses, and associations. The rapid growth of Argentina’s railroad system aided in the transportation of people from Europe, Africa, and Asia who mostly arrived to the Port of Buenos Aires by boat, but then continued into the country’s “interior” to find agricultural and other labor opportunities.

Amidst this flow of immigrants were thousands of Arabic speakers from the Eastern Mediterranean, who arrived in Argentina as part of themahjar – a global diaspora. Upwards of 100,000 people from the current day area of Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine came to Argentina before WWII, and today we can find evidence of that community’s heritage in every single province. More and more scholarly studies of Arabic-speaking immigrants in Argentina are providing us with a better understanding of what people’s lives and livelihoods looked like – especially in large urban hubs such as Buenos Aires, Córdoba, or Tucumán. There were, however, many Arab-Argentines who made their homes in small towns and frontier spaces, far from any urban grid. Take for example the capital of Patagonia’s Tierra del Fuego Province: In Ushuaia (the southernmost city in the world!), one of the earliest settlers was Barcleit Fadul. This man came from Lebanon, and arrived in 1912 to begin his life as a merchant along the Beagle Channel. At the time, Ushuaia was but a small outpost of less than 1,500 inhabitants. Most of those who did live there were, in fact, inmates in the prison that the Argentine government had decided to build there in hopes of establishing greater dominion over the “Land of Fire” (Tierra del Fuego) territory. Subsequent generations of the Fadul family produced Esther Fadul – one of the first women to be elected as diputada nacional (congressional representative) in Argentina, and Liliana “Chispita” Fadul, current diputada nacional for the Province of Tierra del Fuego. While there are certainly exceptions – such as the Fadul family – we tend to know far less about the people in the rural Argentine mahjar, as their biographies aren’t often featured in the archival sources that historians are able to access.

Business Directories: A Demographic Window

One of the difficulties of compiling comprehensive data on Middle Eastern immigrants and their descendents throughout Argentina is the logistics of gathering archival material from such far-flung places as Patagonia, all the way up to Argentina’s arid northern border with Bolivia. However, there is one type of archival source that has the ability to provide us with a clearer demographic picture of both rural and urban areas, and this comes in the form of the “Guía de Comercio” (“Commerce Guide”). These Guías de Comercio were a set of business directories that were widely advertised and distributed within the Syrian and Lebanese community in Argentina. They functioned much as a “Yellow Pages” guide would function today, and were organized according to profession, surname, and geographic region. The purpose of these directories was to encourage the circulation of trade and assets within the ethnic community. The individuals who gathered the necessary data to compile these directories were intrepid travelers who covered thousands of miles by train, car, and sometimes even on foot.

One of the earlier business directories, titled Guía Assalam de Comercio Sírio-Libanés appeared in 1927, and was the product of a long information-gathering tour undertaken by Lebanese-Argentine journalist Wadi Schamún. Schamún came from an elite Buenos Aires-based family that ran a prominent Arabic-language newspaper (Assalam, 1902-1988). They also operated a printing press for Arabic-language and bilingual Spanish-Arabic books, pamphlets, and magazines. Schamún used the platform of Assalam’s press to print his business directory after spending months touring the length and breadth of Argentina to register business owners. In 1930 and 1936, Schamún again embarked upon tours of the nation to update the listings for a second edition of the Guía. It is worth noting, before we proceed any further, that there is hardly any useful Argentine census data from the first half of the twentieth century that would help us to formulate a comprehensive picture of where Syrian- and Lebanese-Argentine people lived, or what they did to make a living. For this reason, we really have to depend on archival materials (such as these business directories) that were generated within the immigrant community itself.

From approximately 1940 to 1942, the businessman Salim Constantino, who hailed from the central Argentine province of Córdoba, followed in Schamún’s footsteps and set out to make his own business directory. He traveled through every province and unincorporated territory, stopping in major cities such as Mendoza, San Juan, and Rosario, and also in tiny towns in remote areas. In each section of the directory, which was organized geographically, he included directions on how to reach every one of the municipalities listed by railroad. For those located far from the beaten path, he included the closest railway station possible. In 1942, he published an elegant hardbound business directory, complete with gilded cover. In his introduction to the directory, Constantino wrote: “The interior of this country bears eloquent witness to the many labors of progress [made by Arab-Argentines]… Wherever they have come to settle and work, they have left their indelible mark.” In a way, the business directories compiled by individuals such as Constantino or Schamún are one of the few archival documents that do not heavily privilege the presence of urban populations over that of their rural counterparts. This is one of the factors that makes this material an excellent set of data for the digital history project that we have been working on here at the Khayrallah Center since January 2016.

Creating a Digital Resource from the Guía de Comercio

We began the process of digitizing the 1942 Guía de Comercio Sírio Libanés by manually compiling all of the information for each province or territory into a single database. In total, our sample size was 10,040 entries, each of which consisted of the name of an individual, their type of business, and their address. We purposefully created a bilingual Spanish-English database of all of the occupational information so that in the future we will be able to integrate this data set with that of other English-language business directories, or Arabic-language business directories that we have translated into English (such as the Syrian Business Directory of 1908-1909, published in New York).

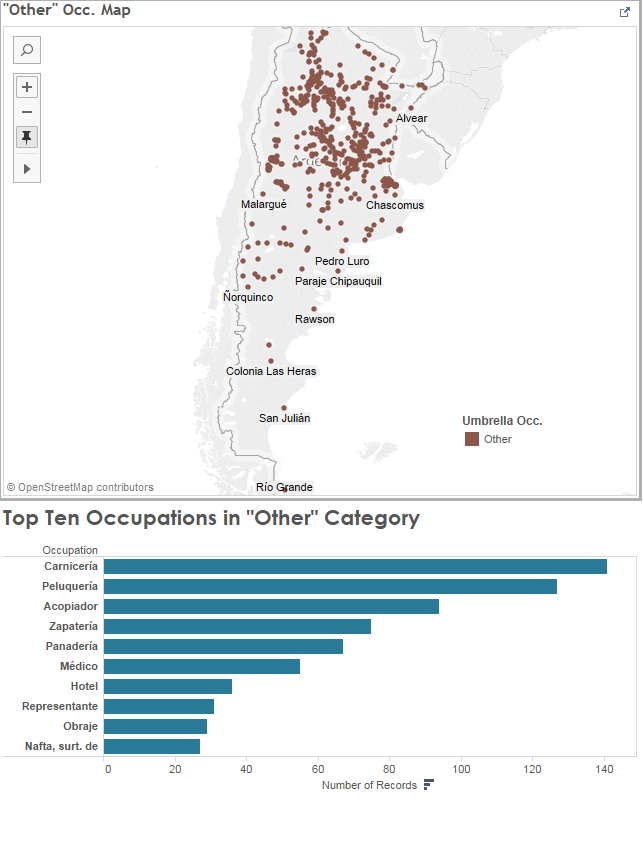

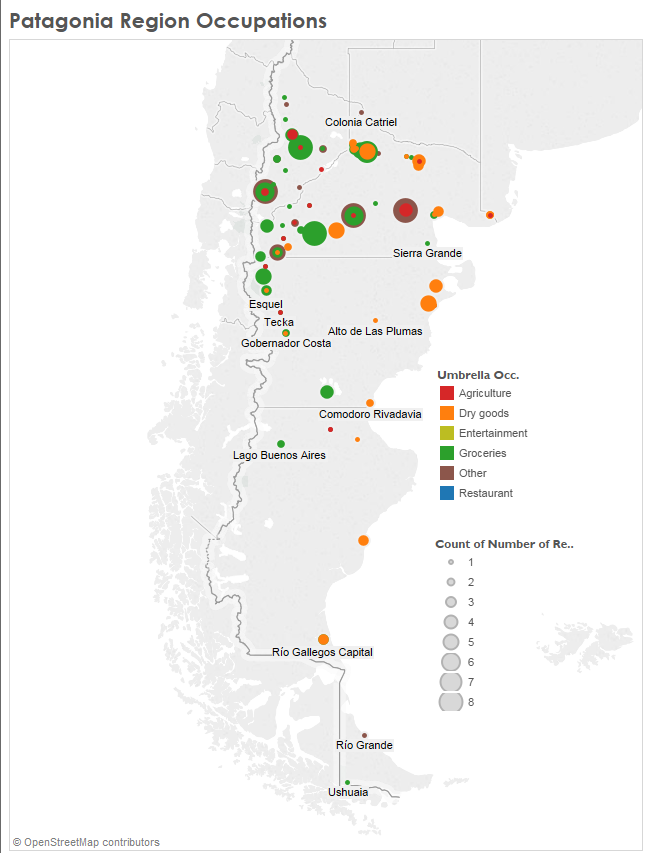

We sorted the data by region (province or territory), and then broke it down into principal thematic categories that represent broad themes under which we could group multiple professions. These categories included: Agriculture, Dry Goods, Entertainment, Grocery, Restaurants, and Textiles.

For businesses that did not fit into any of the umbrella categories, we labeled them as “Other.” Within each thematic category, we specified the exact nature of each business – a highly diverse array of jobs ranging from hairdressers to locksmiths – so that we could run specific analyses of certain types of professions, or track occupational diversity in a particular region beyond main thematic categories such as agriculture or textiles.

We also batch-converted all of the addresses in the directory to procure GPS coordinates that would allow us to accurately map the thousands of locations represented in our 10,040 person sample. For this first round of analysis we utilized Tableau Public software, and hope to expand this project to include ArcGIS mapping technology in the future.

Data: Occupational Trends

Of the principal thematic categories, “Grocery” was the most common occupation listed in the directory, with approximately 40% of businesses (4,133 entries) falling under this category. Second to grocery businesses were those in the general category of “Dry Goods,” which represented roughly a third of the total occupations from the sample (3,252 entries). These two types of businesses were reported from every single province and territory in 1942, with the exception of the National Territory of Tierra del Fuego (now Tierra del Fuego Province since its political incorporation in 1990), which did not report any dry goods businesses.

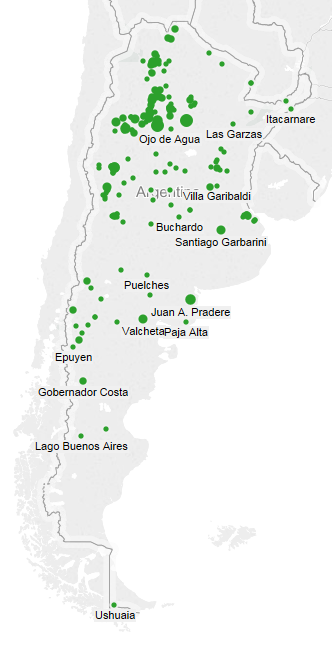

The highest reporting regions were northern and central Argentina, with the provinces of Buenos Aires, Santa Fe, and Córdoba reporting the largest numbers of businesses (3,907 entries combined). The Patagonian region, which is comprised of the current-day provinces of Río Negro, Neuquén, Chubut, Santa Cruz, and Tierra del Fuego, was the most sparsely populated during this period, and it logically follows that it reported the fewest number of Syrian and Lebanese businesses (approximately 3% of the nationwide sample). The maps of businesses in sparsely populated rural regions such as Patagonia provide us with the first visuals ever created that represent the immense dispersal of this diaspora population in Argentina. While the Arab-Argentine press in major cities such as Buenos Aires, Tucumán, and Córdoba often made mention of fellow “co-nationals” living in the far reaches of the southern territories, the maps that we produced from this Guía de Comercio represent the first comprehensive visualization of this diaspora’s geographic scope.

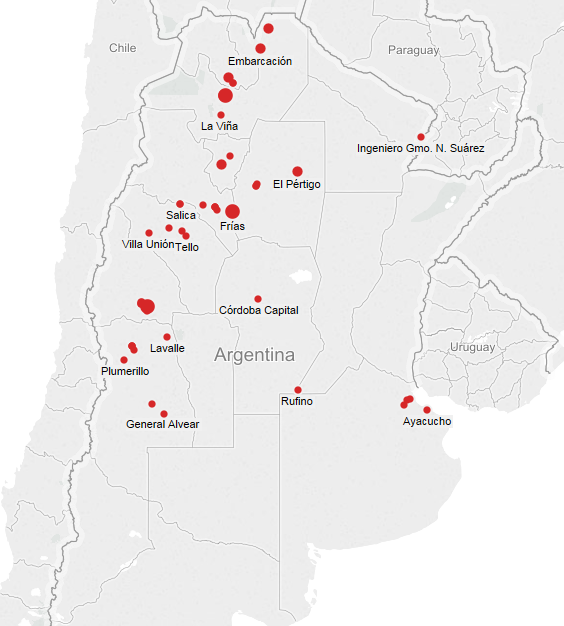

Just as the Khayrallah Center’s earlier work with U.S.-based business directories, census records, and death certificates has produced results that challenge old myths about the first generation of Levantine immigrants in this country, the 1942 Argentina directory also helps us to nuance our understanding of what this diasporic population did for work. The digital database that we have created for the Argentine business directory, in combination with the Tableau analytics platform, allows us to retrieve and isolate information about professions that are not commonly mentioned in other archival materials that pertain to this community, such as the immigrant press. For example, within a larger map of all agricultural professions, we can see a clear belt of Syrian- and Lebanese-owned viticulture businesses ranging from Mendoza province northward into Salta province.

The time period represented by this data set reflects an era in which Argentina, one of the world’s foremost producers of wine today, was only recently beginning to experience a revitalization of its viticulture industry after the Great Depression. Regardless of whether Arab-Argentines worked in the viticulture industry, or other sectors of agriculture, the stories of these individuals are not ones that tend to be highlighted in community histories that privilege the actions and agendas of urban elites. Directly countering these urban-focused narratives, this database contains evidence of 297 people’s presence in diverse niches of the wider agricultural sector ranging from stock breeders, to dairy producers, to farmers.

Looking Ahead

In looking ahead to our next steps with this project, we have two goals: First, we want to continue to create materials that will be useful, and accessible, to a wide audience of scholars, students, and people with heritage ties to this diaspora. Dr. Balloffet is already working on some Spanish-language resources to share with people whose relatives or ancestors appear in the 1942 Guía de Comercio. Second, we want to expand our database to include business directories from earlier time periods in Argentina (such as Wadi Schamún’s Guía de Comercio Sírio-Libanés 1927). This will provide us with important axes of comparison, and will allow us to track change over time in occupational and other demographic trends. A cursory look at a small sample size from the 1927 directory already shows us that certain individuals who appear with one profession in the 1942 guide held very different posts than when they were surveyed for the 1927 guide. For example, Lebanese-Argentine cinematographers José Dial and Roberto Curi, who were active documentary and dramatic film makers throughout the 1930s and 1940s, are listed as being a “fruit vendor” and a “merchandise vendor,” respectively, in 1927. Within less than two decades, each of these individuals moved from being small-time entrepreneurs to professionals who traveled internationally, bringing their art to mahjar communities throughout the Americas. In addition to expanding our database on the Argentine mahjar, it would also be fruitful to build data sets from other Latin American-Arab business directories into our ongoing study.

Until now, these business directories have not often been cited extensively in scholarly studies of this diaspora community in Argentina (and indeed the Americas more widely). This is likely because heritage societies, social clubs, and libraries historically did not tend to systematically preserve these guides beyond the expiration date of the information that they contained. These were documents created with utility and practical purpose in mind: they were tools to facilitate the flow of resources within this diasporic group at specific moments in this community’s history. Unlike other archival sources – such as films, novels, or logbooks detailing the lavish holiday celebrations that took place in local heritage associations – these were not necessarily documents created with the goal of crafting a document that would become part of the cultural patrimony of the community. Instead, they were strategically created, and disseminated, to serve as immediate purpose of educating members of the Argentine mahjar about the vast geographic network of which they were a part. In the meanwhile, these directories linked entrepreneurs and helped to activate capital flows.

- Categories: