Moving Beyond the Soundbyte: Refugees and Oral History

This post is written by Renée Michelle Ragin, a PhD student in Literature at Duke University where her research focuses on the negotiation of national identity in post-conflict Middle Eastern and Latin American states. Her last article with the Khayrallah Center focused on war, memory, and archiving.

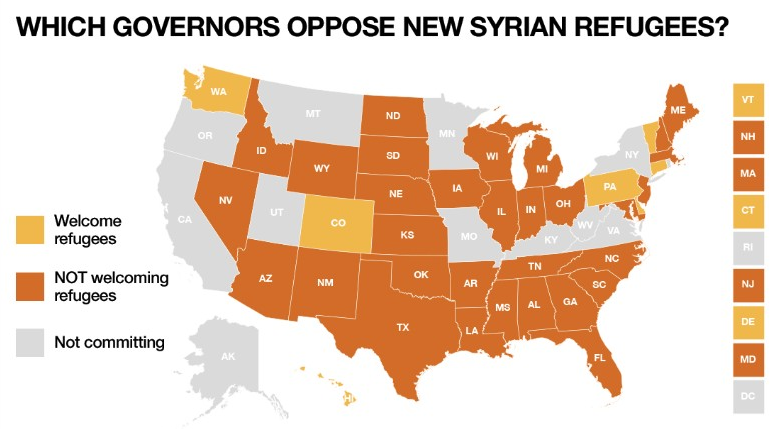

In 2015, approximately 5,000 refugees from around the world resettled in North Carolina, 3,000 of whom arrived from countries of asylum. The overwhelming majority of this population have provenance in the Levant.[1] Last fall, 31 United States governors, including the governor of North Carolina, pledged not to accept Syrian refugees, responding to, and producing, a fear of the “other”: the other as terrorist-in-training, as needy, as a competitor for resources, as different.[2] This pledge followed a series of coordinated terrorist attacks in Paris claimed by the Islamic State, and urgent claims of a “crisis” suffered by European Union member states facing a rapid rise in Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region migrants, due largely to the movement of Syrian refugees.

Alarm-ringing in the US and EU casts the presence of Syrian refugees as urgent, voluminous, threatening and unprecedented.[3] Such a claim seems deaf to the ongoing conflict producing these refugees, to say nothing of the fact that, compared to MENA countries, only a small number of refugees reach Europe, let alone the US. Lebanon, for example, a country of 4.5 million citizens and a GDP of $44.5 billion, hosts around 1.5 million Syrian refugees. By contrast, as of April the US, with a population of 322 million citizens and a GDP of $16.7 trillion (one of the highest in the world) has accepted less than 2,000 Syrian refugees.[4]

In the face of such distortions, oral histories constitute a powerful means to combat and supplement prevailing narratives of the “other.” In both methodology and purpose, they present an alternative to aggregated information produced en masse and dispersed through commercial filters. Traditional media’s closest approximation of this style is the journalistic profile — though one might argue that even the journalistic profile, insofar as it is meant to be either exceptional to or representative of a larger narrative, abstracts the story of the individual in favor of the purpose for which it is being marshalled. The Oral History Association’s statement on General Principles and Best Practices asserts that “oral history is distinguished from other forms of interviews by its content and extent [in that they] seek an in-depth account of personal experience and reflections, with sufficient time allowed for the narrators to give their story the fullness they desire.”[5]

Sanaa Domat, a Syrian refugee resettled in Canada, by way of Lebanon, is one such example:

“For a while, we supported the regime. We thought they had a better grasp of the future of Syria. We thought like this until one of [my husband’s] close friends was wrongfully kidnapped, tortured, and killed by the regime. His body was returned to his family a week later. At that point, we knew this side was not good for Syria, or its future.

… We applied for visas to the US well before the revolution started. We were all denied, so we waited to apply again. At that point, the revolution had begun, so we applied as asylum seekers to the US. We were rejected again. We tried through the humanitarian parole process. We were rejected again. After 4 years, we decided to apply to Canada. We heard they were more welcoming and that people were finding success making it there. So we applied. Several months later we found out our case was accepted.

… Since the airport in Syria is no longer an option, we had to drive to Lebanon (many checkpoints along the way). We got to Beirut and flew to France for our connection. It was the first time I had ever been on a plane… In fact, most of the plane had Syrian refugees going to Canada. It was nice not to feel alone in the process. But the journey was so tiring. The kids were frazzled and confused; no one was able to sleep throughout the journey. After two days of travel, we arrived in Montreal.

At first not well at all, my youngest one, Jad, started exhibiting some psychological responses to the move. He wouldn’t eat or sleep. He cried a lot, and told us that we were punishing by taking him out of Syria. In the middle of the night, he will wake us up and tell us that he misses a certain person in Syria. At school, the teachers say he will often sit and cry… My oldest son is a lot better, but around Jad, he also talks about Syria a lot.”[6]

Although the refugee crisis has been a constant story in global media, we rarely get an opportunity to hear refugees tell their stories in their own voices and without the constraints of a soundbyte. While not without its obstacles, this model of outreach to a population both vulnerable and resilient is not only crucial to the de-stigmatization of those pre-labeled “other” and “refugee,” but also to the civic injunction to know one’s community, making the oral history projects occurring across the Triangle area, and across the country, a vital part of successfully adaptation to a new reality.

Sources

[1] Interview conducted by Lily Doron with Adam West, Director of World Relief Durham (a refugee resettlement agency). 30 March 2016.

[2] “More than half the nation’s governors say Syrian refugees not welcome.” 19 November 2015. Accessed 10 May 2016.

[3] Akram Khater’s recent article, “‘Syrians’ and Race in the 1920s,”about the longstanding discrimination and prevailing prejudices against Arab immigrants to the US, and Arab-Americans serves as a helpful reminder that in the current environment, plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

[4] “U.S. Has Taken In Less Than a Fifth of Pledged Syrian Refugees” http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/11/world/middleeast/us-has-taken-in-less-than-a-fifth-of-pledged-syrian-refugees.html 10 May 2016. Accessed 4 June 2016.

[5] Oral History Association Principles and Best Practices.

[6] Domat, Sanaa. Interview by Sandy Alkouthami. Arabic Communities. Duke University, 2016. Web. Accessed 10 May 2016.

- Categories: