Teaching the History of Lebanon

This article is written by Dr. Akram Khater, Director, Khayrallah Center and Professor of History at North Carolina State University.

In 1989 a national committee was convened in Lebanon to write a singular history textbook to be used by all schools. In the intervening 25 years the committee has failed to reach a consensus and to produce a unifying historical narrative of the country, and was ultimately disbanded. Today, official textbooks still stop in 1943, the year of independence from the French, sweeping all the subsequent events under the proverbial rug. More damaging is the fact that many schools provide their own highly sectarian versions of Lebanese history, thus reinforcing political, economic and religious divisions, and deepening the divide within Lebanese society around national identity. However, this is not a new problem, but one that goes back to the 19th century, when Lebanon was part of the Ottoman Empire, and it is a legacy that has contributed to the country’s (un)civil wars.

Very early on in Lebanese history, formal education–especially secular education–came to be seen as a critical tool for social, cultural and economic development. In this sense, Lebanon was quite unique. While major Middle Eastern cities like Cairo and Istanbul had venerable institutions of higher learning dating back centuries (like Al-Azhar University in Cairo), the rest of the Ottoman Empire–and most parts of the world, really–was mired in illiteracy and constrained by a very limited scope of knowledge. (Today, Lebanon remains a remarkable place with some of the top universities in the region, and highest rate of education among its population.)

It was missionaries who were the catalysts for bringing higher education into the villages and hamlets of the Lebanese mountains and neighboring cities like Aleppo. Jesuit missionaries first arrived in the Eastern Mediterranean in the 16th century when the Ottoman government allowed European clerics to attend to the spiritual well being of European trading communities located on coastal towns and hinterland cities. This initiated the first sustained and transformative contacts between the Roman Catholic Church and its Maronite counterpart in Mount Lebanon and Aleppo and led in 1584 to the establishment of the Maronite College in Rome by Pope Gregory XIII (who also institutionalized the Georgian calendar). The Maronite College produced practically all the key Maronite intellectuals within the church, including Butrus al-Tulawi, Butrus al-Ghustawi and Patriarch Istifan Duwayhi, who wrote Tarikh al-Azmina (The Chronicle of the Times) the first history of the Maronites and Mount Lebanon. Many of these graduates established their own schools like Patriarch Yusuf Istifan founded the famed College of Ayn Warqa in 1774.

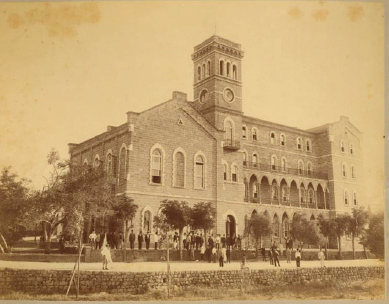

However, the Maronite College in Rome and Ayn Tura and Ayn Warqa in Lebanon were graduating only dozens of students every year, thus limiting their impact on the larger population. Moreover, their training–while including history, geography, arithmetic and languages–remained focused on producing literate Maronite clerics. It was only with the arrival of American Presbyterian missionaries in the 1830s that education in Lebanon took a quantitative and qualitative leap. After failing for years to attract converts from among the Muslim and Christian communities, American missionaries decided that education and medical training were the best ways to reach these communities more effectively. And, so, in 1863 Dr. Daniel Bliss founded the Syrian Protestant College, which was later to be called the American University of Beirut. Fearing that this would succeed in attracting the Christian Maronites and Melkites of Lebanon to Protestantism, Jesuit missionaries responded in 1875 by founding the Université Saint Joseph as a Catholic institution of higher learning. What followed was a fierce competition over the ability to shape the education of Lebanese children, and helped proliferate the number of schools in Mount Lebanon into the highest in the Ottoman Empire. Equally, the curriculum itself changed to become more predominantly secular. Finally, philanthropic Lebanese immigrants to the Americas helped fund schools in their natal villages and towns

However, most of these schools–which were not subject to the central authority of the Ottoman government–remained highly sectarian in their make-up and curriculum. With few exceptions, children of one religious community attended schools that were predominantly if not exclusively for that community, and they learned history from the narrow perspective of their community. While the Ottomans founded their own schools and Ministry of Education in 1847, they did not have the resources to compete with the missionary schools, and the majority of students were attending the latter. Nor could Nahda (19th Century Arab Renaissance Movement) intellectuals like Butrus al-Bustani and his non-sectarian National School overcome the religious divides in education. And thus, as Sandra Mackey, the author of Lebanon: A House Divided, writes:

Lebanese youth entered the foreign mission schools and emerged twelve years later ignorant of everything concerning the history, geography, and social life of their own country. Further, children passed through the schools of their own confession, often barely meeting children of another faith.

This state of being continued well into the Mandate period, when the French controlled Lebanon between 1920 and 1943. Seeking to placate opposition to colonial occupation of Lebanon, the French allowed the Zu’ama, sect-specific powerful Lebanese families, to run local affairs. “Since these groups each had their own ‘district’ of influence and their own religious and political agendas, education was dealt with in a manner befitting each district’s will. This clearly worked against an idea of a unified Lebanese nation and sectarian harmony adding to the sectarian divide and perpetuating sectarianism among Lebanese youth.”

The French also maintained their position of power by decreeing the French language as the priority means of official communications. Because French was predominantly used in Christian schools and higher education institutions, this favored graduates of French-oriented schools even as it disadvantaged graduates of predominantly non-Christian schools where Arabic was the language of instruction. This fueled feelings of inequality and undermined upward mobility amongst the more marginalized sects.

Moreover, the lack of funding for public education (the French administration funneled educational funds through existing private schools that were predominantly sectarian) meant that students from different religious groups continued to learn different narratives about the history of Lebanon. The Lebanese constitution reflects the realization made by some politicians after independence in 1943 that the education system must be at the forefront in the social battle against sectarianism:

Chapter 2, Article 10 – Education, Confessional Schools Education free insofar as it is not contrary to public order and morals and does not interfere with the dignity of any of the religions or creeds. There shall be no violation of the right of religious communities to have their own schools provided they follow the general rules issued by the state regulating public instruction.

Privately run schools were thus brought under the wing of the Ministry of Education and Higher Education, subjecting them to the same national curriculum being taught in state-run schools. Steps were again taken by the government to encourage cohesive social and political orientations through an initiative enacted in 1946. This outlined an addition to the 1944 curriculum on the principle that political and social unity would result from teaching all students the same content. But, the plan for a universal curriculum was hindered by religious schools, working under pressure from constituent donors, as well as the inconsistency of the Lebanese government.

After the civil war (1975- 1989) there was a widespread recognition of the need to create a more cohesive national educational curriculum centered on a common historical narrative that would bring the Lebanese together. Thus, in 1994 a plan for educational reform was released. It aimed at

“Strengthening national affiliation and social coalition among students…with emphasis on national upbringing and authentic Lebanese values.”

What these authentic Lebanese values might be was unclear, as “being Lebanese” was still undefined in history books or in contemporary terms. Hence, the reforms, along with the proposed national history curriculum, became just the latest in a long line of failed initiatives calling for unity amongst Lebanese youth. The reality remains today that “civic education is still being fed to largely homogeneous populations lacking the potential for student to student interaction between different sects.”

- Categories: