Southwestern Syrians: Los Arabes of New Mexico: Compadres from a Distant Land

This article is written by Dr. Jay Price, Director, Public History Program at Wichita State University. His publications include Gateways to the Southwest: The Story of Arizona State Parks, Wichita, 1860-1930, Wichita’s Legacy of Flight, and El Dorado!: Legacy of an Oil Boom. Price’s work was featured twice on the Center’s blog in an article about the Lebanese in Kansas and here again on his co-written article about entrepreneurship among Lebanese in Kansas.

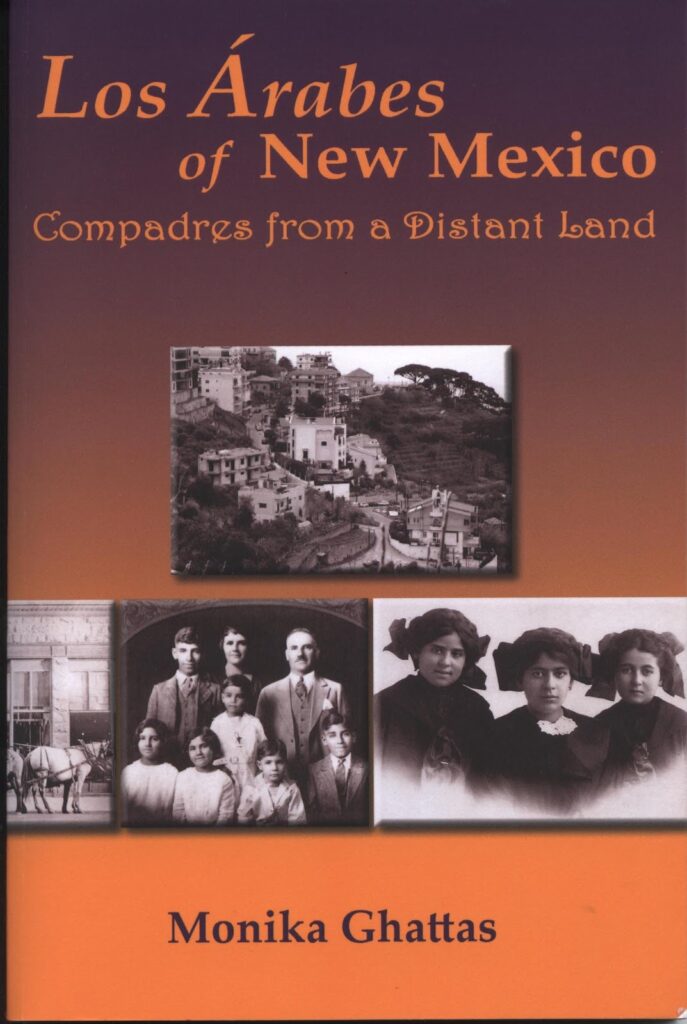

Monika Ghattas. Los Arabes of New Mexico: Compadres from a Distant Land. Santa Fe: Sunstone Press, 2012.

A significant element of the New Mexico story in the late 1800s and early 1900s involves merchant families who established themselves in both small villages and larger cities. Their backgrounds ranged from Anglo to German, Jewish to Greek, and their influence has remained a part of local culture and life ever since.

One such group involved Arab immigrants, often called Syrians or Lebanese, who arrived in the late 1800s as peddlers and then transitioned into small town store owners. Their children continued the entrepreneurship tradition by operating networks of hotels or movie theaters. Their names have remained on storefronts, street signs, and local maps. Among them are Maloof, Budagher, Bellamah, Tabet, Sahd, Abousleman, Salmon, Fidel, and Koury.

The stories of these families form the core of a book by Monika Ghattas entitled Los Arabes of New Mexico: Compadres from a Distant Land. Using the Spanish term for these Arab Americans, Ghattas’ detailed research shows how networks of families mainly from Zahle and the Mount Lebanon region (Roumieh in particular) started arriving in the late 1880s and quickly established themselves in New Mexican life. At first they were peddlers. Later, they ran stores in small towns like Peñasco, Pecos, and Budaghers. Some were tied to Native American/Puebloan communities. Others established presences in larger places like Las Vegas, Santa Fe, and Albuquerque, becoming prominent business figures, community leaders, and even political candidates. Ghattas’ book explores in detail the genealogies and stories of these individuals and their descendants, carefully connecting their efforts to a growing scholarship on the Arab American experience.

Many aspects should be well familiar to scholars of the general history of Arab communities in America. Among these are the stories of chain migration and how families could trace their descent back to a handful of villages in Lebanon, in this case Roumieh and Zahle. Peddling was the key occupation for many of the early migrants, who, as they become more established, settled down to run small stores. The tradition of entrepreneurship continued in subsequent generations.

Los Arabes of New Mexico places these efforts into a larger context. Early chapters explore how the common narrative of early Syrian migrants fleeing persecution and lack of opportunity has remained a common narrative among Lebanese. Going beyond classic “fleeing persecution” or “rags to riches” explanations, Ghattas considers current scholarship that suggests restrictions on opportunity back in Syria may actually have come from strict family dynamics instead of Ottoman religious policies. Moreover, Ghattas develops a number of additional insights, such as the role and scale of Arab migration through Mexico.

The book’s most worthwhile contribution, however, is the way it shows how the Syrians of New Mexico differed from their colleagues in the East and Midwest of the United States. New Mexico’s relative tolerance for various ethnic groups such as the Jews and the Basques made the region generally hospitable to the Arabs. Moreover, the Syrians of New Mexico tended to be Maronites, unlike, for example, the primarily Eastern Orthodox Syrians of Kansas and Oklahoma. The Maronite connection to the Roman Catholic Church enabled Los Arabes to have comparatively easy interactions with New Mexico’s Hispanic Catholic milieu, aided by the fact that a number of Syrian peddlers traded in Catholic religious items.

This ability to blend with local culture stands out in the Los Arabes story. Arab immigrants in the South struggled to present themselves as white in the face of a highly segregated society. Syrians in the Midwest maintained themselves as unique enclaves where families married within their own tight circles and religious institutions maintained ethnic solidarity. In New Mexico, Los Arabes grafted themselves into Hispanic society, even intermarrying with local Hispanic families, taking Spanish names, and becoming pillars of Catholic life. In smaller communities they learned Spanish with that language rather than English being the main language of commerce. Ghattas noted numerous instances where a family “never mastered English very well… (and that) the family’s lifestyle was virtually identical to that of their Hispanic neighbors with whom they socialized and shared traditions.”

This integration also distinguishes the Syrians of New Mexico from other communities of ethnic entrepreneurs in the Southwest. In many ways, the stories of Arab merchant families paralleled those of Jews, but their relationship with New Mexican life was entirely different. Jews have long faced the challenge of adapting to the larger culture in order to function as members of the community but not assimilating so much that they lose their distinctive identity. Arabs, on the other hand, had unique cultural features, but also had a more fluid sense of identity, making integration into Hispanic society an opportunity instead of a threat to ethnic distinctiveness.

Ghattas has achieved a balance that is often difficult to reach. Los Arabes of New Mexico covers the basic story of Syrian/Lebanese immigration in a concise, readable narrative, making the book a good introduction to students and the larger public. Meanwhile, it presents a significant number of insights and new perspectives that will be of interest to scholars. Together, these features make Los Arabes of New Mexico an indispensable part of the library of anyone interested in Arab American history.

Syrians have been integrated into New Mexico society for so long that their presence was not always apparent. One reason I enjoyed reviewing this book was because it related to my own experiences as an Anglo growing up in New Mexico. We regularly drove past the Budagher turn off en route to Albuquerque. I went to school with teachers named Koury and Najjar, with a Fidel as my high school principal. It took a book like Los Arabes of New Mexico to reveal that all these experiences were part of a fuller story, a rich and dynamic story whose influence is just now starting to be appreciated.

- Categories: