Lebanese-Americans in World War I

This article is authored by Dr. Akram Khater, Director of the Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies and Khayrallah Distinguished Professor of Lebanese Diaspora Studies, and Professor of History at NC State. His latest article focuses on complicating the Lebanese peddler myth.

Like other immigrant communities to the US, the Lebanese have fought in many of America’s wars. They were driven by patriotism, a sense of adventure, a desire to assert a modern masculinity…or they were conscripted. Yet despite their service over many decades, their stories have rarely been told, and even now they remain mostly anonymous, or at best appear as an entry on a list of names. (A major exception to this is the wonderful exhibit curated by the Arab-American National Museum and titled Patriots and Peacemakers: Arab-Americans in Service to our Country). To narrate their history, and integrate it into the larger story of America, we need to collect sources and material that give substance and insight into their individual and collective service. In other words, we need to render them as visible and human actors who defended America, enthusiastically or reluctantly. One such source is a book by Jibrail (Gabriel) Elias Ward al-Tarabulsi (from Tripoli), titled The Syrian Soldier in Three Wars, that the Khayrallah Center has just acquired through a generous donation by Dr. Linda Jacobs. (With the generous support of the digitization team at the American University in Beirut Jafet Library, the book is completely searchable in Arabic).

The Syrian Soldier in Three Wars presents a unique window into the life of its soldier-author, and the Lebanese community’s response to his military service and that of his fellow immigrants. Written in 1919 (and published by Salloum Mokarzel’s The Syrian-American Press in New York), the book starts with the author’s declaration that he only sought to write his memoirs to avoid their loss to time, and to list events “and psychological factors that are neither seen nor felt except by those who witness war.” At once distancing the great majority of Arabic readers from these realities and yet promising them enthralling intimacy, the book was written with a mixture of seriousness and levity. It contains various entries that include, among other things, an essay on the American Flag, which for the author stood for “true right to divinely ordained human liberty”; a short biography of Teddy Roosevelt; President Woodrow Wilson’s speech on why the US entered WWI; and short biographies of Nicholas II, the Czar of Russia, and Ottoman Sultan Muhammad Rashad V. But what is most personal and thus interesting about this book are two other sections. The first includes the reflections of the author on war in general, and his memoirs from three particular wars he fought in (Spanish-American, Phillippines and WWI). The second is “salutations’ from poets and merchants of the community to the author and the “Syrian Soldier” in general.

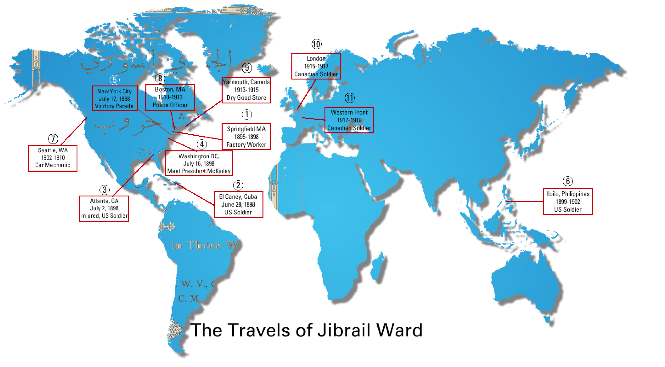

It is in these two sections that we find rich historical material about the author’s perspective on war and his experiences, as well as how some members of the community looked upon their conscripted or enlisted soldiers. Jibrail Ward starts out by noting that the main cause of war and all of its horror is greed: the desire of individuals and nations to gather unto themselves, and control, a greater and greater share of earth’s bounty. From here he describes–with a mixture of humor, honesty and sobering recollection–his journey to becoming a soldier and fighting with Teddy Roosevelt in Cuba, then subsequently in the Philippines and finally in the trenches of Europe during WWI (here as a Canadian soldier swearing allegiance to the English king!).

An example of this mixture appears early on in his narrative when he described the march onto Cuba. After enlisting on a dare with a group of Irish friends–with whom he lived–in Springfield, Massachusetts, he was shipped to Cuba in June 1898. Ironically-and irony suffuses this book- despite his disdain for greed as the cause of wars, Jibrail was not averse to making a little extra cash when the opportunity presented itself. For instance, at the outset of their march to the front each soldier was given, amongst other things, cans of food. In the heat of the march many dropped the cans along the road, and Jibrail would swiftly pick them up and carry them until he had filled an improvised sack. In the evening, after they had set up camp, soldiers who had dropped some of their supplies felt pangs of hunger and went to Jibrail who sold back to them the cans and bread for a dollar a piece making $60 in one night. This entrepreneurial instinct is pronounced throughout his story such as when he sells his military cap (with a hole in it from a cigarette burn) to a civilian in Richmond, Virginia by claiming that the hole was made by a bullet in Cuba.

A few days later, on June 30, at the battle of Al Caney, Jibrail came face to face with real war for the first time. His previous levity was replaced with dread as the battle began. He wrote, “I cannot hide from my dear reader that with the first bomb I became frozen…and shaking with fear.” After an hour of being petrified, he gathered “his military courage” and stood up and started fighting. Here the tone shifts again to a celebration of war which he described as “a wedding” and himself and his fellow soldiers as “lions.” In a brief sequence, Jibrail goes from being a–stereotypical “Syrian”–peddler, to a frightened man cursing the impetuous moment of enlisting after a bout of drinking, to a lion charging forth and dispatching enemy soldiers with joy. Another few hours after this initial battle Jibrail was wounded. Three days later, he was shipped back to Key West and transported to Atlanta for hospitalization.

Jibrail’s narrative continues across several US states, two other continents, and two more wars, It details the daily life of soldiers at the front, his attempt to recruit more Syrians into the US Army, and later to exhort his fellow “Syrians” to join the fight against the “Turks” in Lebanon and Syria. Neither was terribly successful, but the community–in another bout of irony–nonetheless heaped praise on him for his service in newspaper articles, banquets, and other honors they bestowed upon him. The dissonance between the reluctance of the great majority to volunteer for war and their rush to salute Ward’s bravery was not lost on the author who complained bitterly “that no one answered my call.” Even without calling it “cowardice” this reluctance appears “un-manly” in light of the accolades that he and others heap upon those who did volunteer, and that he heaps upon himself within the context of his self-narration as a valiant warrior. Indeed, The Syrian Soldier in Three Wars presents a great tool for understanding how the idea of “masculinity” is construed by the author–and to a lesser extent the community–through panegyrics to bravery and war in poetry and advertisements, as well as anecdotes about about men and women.

Finally, and as noted earlier, the books includes a listing of many Lebanese soldiers who mainly served in WWI. Among them are:

- Ali Kleib

- As’ad Raji Qabalan

- Ayyoub Nakd Ridwan Mikhail

- Ayyoub Sulayman Hatem (Sergeant)

- Boutrous Roumanos (killed in action)

- Costa Ibrahim Srour

- Dandy (Constantine) Niqula Malouk

- Daoud Ali

- Daoud Salem

- Eid Hanna Eid (killed in action)

- Fayez Salloum

- Fouad Az’oun

- Fouad Bishara

- George Dawaleebi

- Hanna al-Bahhar

- Hanna al-Hashash

- Hanna ibn Yaqoub al-Ratl

- Ibrahim abd al-Qassis

- Ibrahim Jirji Marqadi

- Jibrail Bishara (killed in action)

- Lieutenant Najob Dammous

- Mahmoud Hassan

- Mansour Amin Mansour Shuqayr

- Michel Amer al-Taqshi

- Mitri Abd al-Nour

- Mohsen As’ad al-Z’ayteeni (killed in action)

- Najib al-Khouri

- Najib Eid Boutrous

- Nassif Charbil

- Niqula Elias Hobeikah

- Qaysar Haddad (brother of Nadra Haddad, owner of al-Sa’ih Arab-American newspaper)

- Rafleh al-Kharj

- Salim al-Taweel

- Salim Khalil Abi Hamra (Sergeant)

- Sayf Baddour

- Sergeant Mikhail Yousef Shehadeh

- Sergeant Nadim Youssef Halabi

- Sergeant Youssef Hanna al-Numayr

- Shehadeh al-Bardawil al-Shuwayfati

- Shikri Baddour

- Wadi’ Sarofim

- Youssf Shibli (killed in action)

From this it appears that only a small percentage (0.08%) of the 120,000 Lebanese-American community served in WWI, as opposed to the 1% of general American population that served in France during this period. However, a higher number is reported in a book titled, Prairie Peddlers: The Syrian-Lebanese in North Dakota and compiled for South Dakota by William C. Sherman, Paul L. Whitney, and John Guerrero. There, it appears that 50 out of the 750 members of the Lebanese-American community were either inducted or enlisted into the US Armed forces, which translates to 6.67% having served at one point or another during WWI. Given the wide range of numbers, it is safe to assume that we do not have as yet an exact tally of those Lebanese-Americans who served in the first world war, and this is a project yet to be undertaken.

Regardless of the numbers, what is apparent is that many did indeed serve and some felt that it was part of their duty as newly minted Americans. More to the point, with Ward’s book we can begin telling far more intimate and detailed stories about how early Lebanese immigrants experienced–and looked upon–military service: as a citizenship rite of passage; as a means of proving manhood; and as traumatizing moments punctuated by boredom, opportunism, fear and violence.

PS: Mr. Charles Samaha, who has just completed a biography of his uncles Faris Maalouf, notes that Lebanese-American soldiers in WWI were–along with homosexuals and African-Americans–given a disproportionate number of “Blue Discharges” after the war. This means that they were not eligible to become US Citizens or receive the GI Bill. It also meant that they faced discrimination in obtaining work since employers would not hire veterans with “blue discharge” papers. It was only when H.R. 11175 was passed by the US Congress in May 1936 that Lebanese-American soldiers could apply for naturalization under the Veterans’ Naturalization Act.

- Categories: