Annie Abdo: A Peddler . . . A Tulsa Woman

This post was researched and written by Randa Hakim, Claire Kempa, Marilyn Drath, and Marjorie Stevens.

Annie Coury Abdo was a first-wave Lebanese immigrant to the United States whose life both defies and exemplifies elements of the traditional cultural and historical narratives of Lebanese immigration. Annie rose from peddling to property ownership, a trajectory that embodies the American Dream. Uniquely, however, Annie indirectly serves as one origin point for the way in which American popular culture understands Arabs: she knew Lynn Riggs, author of the play that would become Oklahoma!, and he incorporated both a close variation of her name and her early career as a peddler into his work. While this work created and perpetuated negative stereotypes, the real Annie cannot be reduced to a fictional archetype: she was a complex woman with many identities, all united by her intelligence and quiet strength. Annie’s story provides rare insight into important, rarely-told aspects of early Lebanese immigration: the lives of women, and the experiences of immigrants who settled in the American West.

Annie was born around 1859 in a village called Saghbine, located east of Sidon, in the mountain range called the Lebanon Mountains or Mount Lebanon. At the time, this area was known as Greater Syria, and was a province of the Ottoman Empire. [1] Therefore, in the eyes of Annie, her homeland was a province of the Turks. However, identity in Syria was distinct from that of the Turks or Ottomans: most people identified closely with their religion and with their village or region. Annie was born into the Coury family of Saghbine, a Maronite Catholic family. [2] This identity was foundational: growing up, if asked where she came from, Annie might answer, “I am a Maronite Christian” as easily as her descendants might respond, “I am an American.”

Annie married Alfred Abdo Kahwaji, the mayor of Saghbine. The date of their marriage is unknown, but likely took place in the 1870s. She took the role of stepmother to Barsheva, and she and her husband had four more children together: Delia, Joe, Edward, and George. Annie immigrated to the United States sometime around 1890. At this time her eldest child, Delia, was aged twelve, Joe was eleven, Edward was seven, and George was just two years old; Barsheva’s age at the time is unknown. Annie went first to Nebraska, which had been a settled state since 1867. Unable to make a living there, she moved to Iowa and Kansas, searching for greater opportunities.

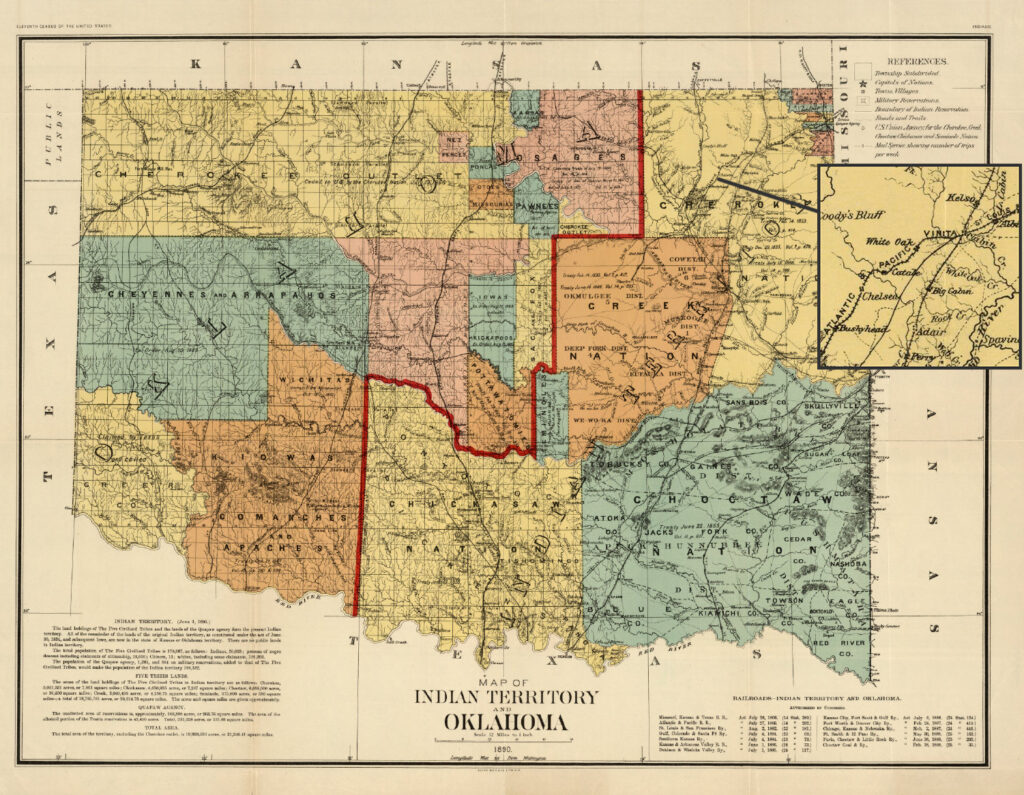

Annie’s search for a place to settle ended in the Oklahoma and Indian Territories. Like many immigrants, she was drawn to live near family: she went to Oklahoma to join her brother, Charley Coury, who was living in a small town named Chelsea. When Annie arrived in the 1890s, Oklahoma was not yet a state. Instead, the whole area was divided into territory belonging to various Native American nations—including, notoriously, the nations who had been expelled from their homes in the southeast under Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act of 1830—and land that the federal government had earmarked for the Plains Indians. After the United States government opened some of the unassigned lands to settlement in 1889, the government set about acquiring—sometimes by purchase, but often by manipulation of treaty and law— large swaths of land predominantly owned by the Cherokee, Creek, Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations. As a result of the land booms, the Cherokee land, where Annie arrived, was rapidly developing, with many new towns arising along the railroad line. Annie moved through these towns throughout the 1890s, going from Chelsea to Claremore to Tahlequal before settling, finally, in Vinita.

Annie’s search for home, however, was incomplete without her family. In the mid-1890s, three years after her immigration, Annie returned to Saghbine for her children. She brought her two eldest sons, Joe and Edward, and her step-daughter Barsheva back with her to the United States. Annie left behind her fifteen-year-old daughter Delia to care for her youngest son, five-year-old George. After several more years of saving, Annie amassed enough money to send for her eldest daughter and youngest son. Delia, however, couldn’t wait: knowing the money was coming, she borrowed the amount locally and came by herself. Annie’s youngest child, George, followed soon after.

Like many Lebanese families, years of separation had a deep impact on family bonds. When sixteen-year-old George Abdo arrived at the train station in Vinita, his brother Edward did not recognize him. Confused, George continued on the train’s route until the conductor realized the young foreign boy was lost and sent him on another train back to Vinita where the entire family was finally reunited. Family was incredibly important to Annie and her children. Over the years, Annie always kept a home ready for her children to return to no matter where they went. Due to the ruptures of immigration and migration, Annie’s need to provide security for herself and her family was strong.

Annie funded the immigration of her family through her work as a peddler. While early Lebanese historians and descendants have often viewed peddling in a positive light, as the first rung on the ladder of economic success, in broader American culture the phrase has often evoked negative associations. From this perspective, “peddler” often refers to itinerant outsiders, viewed as racially or economically “other” than the communities to which they sold goods. Even within the more positive communal memory, peddling is often seen as a necessary first stage to lead to the more complex career of owning a business.

Annie’s experiences undermine these negative stereotypes. Indeed, it might be more accurate to call Annie a traveling saleswoman rather than a “peddler:” she was a savvy businesswoman, embedded in her locality and well-known and liked by her customers. [3] Annie worked with two Lebanese merchants to acquire goods: Mr. Boutros of Kansas City and Mr. Saffa of St. Louis. They shipped her fine cloth goods such as tapestries, linens, and silks as well as smaller items like tablecloths, laces, and napkins. She purchased these goods on credit, and traveled on foot and by wagon to sell goods; though the range of her sales is unknown, she developed relationships with many people on her routes, often sleeping at her customers’ homes.

Although Annie could not write, she had a keen mind for business: she kept her accounts in her head, calculating orders, expenses, sales, and profits. In order to keep track of her sales, she carried a book which she required purchasers to enter their names, purchases, and what was owed; upon returning home, one of her children would read the ledger back to her and, using her extraordinary memory, she would know whether the written accounting was correct.

Her embeddedness into the social fabric of the Oklahoma and Indian Territories is also likely evidenced in the work of American author and playwright Lynn Riggs (1899-1954). As a young boy growing up on a farm near Claremore, Oklahoma, he encountered Annie. The impression that she left on him, and the tales Riggs’ mother recounted of her dealings with Annie, inspired him to incorporate elements from her life into two plays: 1927’s Knives from Syria and 1931’s Green Grow the Lilacs. While generally unsuccessful as a stage play, Green Grow the Lilacs earned much acclaim in later musical and film adaptations as Oklahoma!. [4] The musical version, debuting on Broadway in 1943, was the first collaboration between Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II, a duo that would go on to earn numerous accolades in the coming decades. The hit musical ran on Broadway until 1948 and a touring version performed overseas for the armed forces during World War II. Oklahoma! grew in popularity after 1955 when it was adapted into film, later winning two Academy Awards. The musical remains popular today and is still being performed in several cities. While a close variant of Annie’s name, Ado Annie Carnes, became immortalized in Riggs’ play and the musical and film adaptations as a silly farm girl, it is unclear how much he based the character on her actual life. [5] Oklahoma! features another character, known as the “pedler” or Ali Hakim, alternatively described as “the Persian” or “Syrian” that also may have been inspired by Riggs’ memories of Annie and her family. Numerous other theories behind the inspiration for the characters exist; some sources suggest that he modeled Ado Annie on members of his extended family rather than his memories of Annie Abdo.

Although it is impossible to say exactly what elements of Annie’s life Riggs drew from in his work, her influence on the Tulsa landscape is clear. Beginning around 1900, she saw the investment potential in the region. Using earnings from her peddling sales, Annie and her sons Joe and Edward purchased some of the best land in Tulsa. In 1905, they bought three acres in the city center on 15th and Peoria Streets for $3000 and paid the debt within five years. In 1907, as Oklahoma prepared for statehood, Annie and her family moved to Pawhuska, a town near the Osage Nation where oil was discovered in 1897. [6] After a short time, they left the area and returned their attentions to Tulsa.

Together with her son Edward, Annie helped expand the family’s real estate investments. They procured land in an area that would become known as the “Abdo Addition,” a neighborhood with modern homes and improvements that was one of the fastest growing areas in Tulsa by the 1910s. Their investment in the area may have been facilitated by Edward’s wife, May, and her parents. May was a member of the Creek nation, and her parents, Alvin and Mary Hodge, were members of the Creek and Cherokee nations, respectively. Large portions of the area that would become the “Abdo Addition” in the 1910s was allotted to Alvin and Mary Hodge by the Creek Nation between 1903 and 1910. [7] The Hodges, and in turn their daughter and son-in-law, possessed advantages when obtaining property, especially in the years prior to Oklahoma’s statehood when the area was part of the Indian Territory. In fact, many of the early property records for the platting and subdivision of the land that would become the “Abdo Addition” list May, not Edward, as the primary grantor, or seller. In addition to developing Tulsa real estate, Annie and her children also invested in farms and raising horses.

On November 20, 1914, Annie passed away at the home of her son Edward. Her funeral was held in Tulsa at the Holy Family Catholic Church, which would later become Holy Family Cathedral. Her son Edward, with whom she lived and conducted business, died two years later, and his wife May, who helped the Abdo’s acquire Tulsa property, in 1918.

Footnotes:

[1] Greater Syria is a historic designation for the area that today includes modern-day Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, and Palestine/Israel. The same rough geographic area is also known as the Levant. At the time, however, its residents were often referred to as Syrians.

[2] Maronites are Christians who belong to the Syriac Maronite Church, under the Patriarch of Antioch. They are identified with the Roman Papacy, but for centuries retained both independence and distinct practices. In Annie’s life, the Maronites were geographically concentrated in the Mount Lebanon area of Syria. Her maiden name, Coury, means “priest,” indicating that some of her family members served in the church.

[3] Her esteem in the community is apparent in an article from The Weekly Chieftain, a newspaper published in Vinita, Oklahoma. In one article from February 1, 1904 (p. 1), Annie and her family are praised and described as “upright, honorable people” who are“intelligent” and “speak English quite well.” A digital copy of this newspaper article is available at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/22194746/the_weekly_chieftain/.

[4] For more information on Lynn Riggs and his writing career, see “Broadway’s Forgotten Man,” by Charles Marrow, This Land, April, 30, 2014, accessed July 5, 2018, http://thislandpress.com/2014/04/30/broadways-forgotten-man/.

[5] “The History Behind the Lyrics of “Oklahoma!” by Savannah Evanoff, News OK, June 22, 2015, accessed July 5, 2018, http://newsok.com/article/5429071 provides some information on Riggs’ inspiration. To access a digital copy of the script for Green Grow the Lilacs: A Folk Play in Six Scenes, see the George Mason University Archival Repository Service, Federal Theatre Project Materials Collection, accessed July 5, 2018, http://mars.gmu.edu/handle/1920/4487. For a digital copy of Hammerstein’s 1942 musical script from Oklahoma!, see https://www.systemeyescomputerstore.com/scripts/Oklahoma/Oklahoma_script.pdf.

[6] The Midland Valley Railway arrived in Pawhuska in 1905. By 1907, when Oklahoma was granted statehood, nearly 200 acres of land had been platted and sold at public auction, attracting approximately 2,400 people to the area. In the 1910s and 1920s, Pawhuska would become well-known due to the Osage oil boom. http://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=PA020

[7] For detailed information regarding the property exchanges and sales in Tulsa, see the Tulsa County Clerk’s Office and Records, Real Estate Services Division at http://www.countyclerk.tulsacounty.org/Home/Land. Here you can access the: Historical Unplatted Tract Index, Historical Platted Tract Index, Tulsa County Plats, and Historical Grantor/Grantee Index. To find records related to the Abdo Addition, look for documents related to Section 6, Township 19, Range 13. For information about the initial three acres Annie purchased in 1905 at 15th and Peoria, see Section 7, Township 19, Range 13.

Additional information collected from the Abdo’ family; Judge Edgar Corey memoires; United States Immigration and Census; Woodlawn Cemetery in Claremore; Local Newspapers; and Tulsa County Clerk’s Office and Records

- Categories: