The Second Jabbour Immigrant: Albert Jabbour and His Courtship Story

This blog was written by Folklorist, Sabra Webber. Webber is a professor emerita at The Ohio State University in the Department of Comparative Studies and the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures. She visited the Khayrallah Center in the Summer of 2018 while researching her former colleague and friend Alan Jabbour. This is the second installment of three blogs about Jabbour’s immigration saga.

Family stories are kind of selective. You get wonderful details but then there are whole blank spots that you know nothing about…. Alan Jabbour

ABDULLAH JABBOUR AND HIS SON

In my first blog, “A Boatload of Horses,” I shared Alan Jabbour’s story of his grandfather’s, Abdullah Jabbour’s, emigration from an-Nabk, Syria in 1893 bound for the Chicago Exposition. Central to Alan’s family immigration saga was the tale of his grandfather’s sea voyage—his trip from Beirut to New York with “a boatload of horses.” We later learned, after discovering Abdullah’s 1893 columns in the Arabic newspaper, Kawkab Amirka,[1] that, as is typical of family sagas, Alan only knew select details of his grandfather’s story. Some details he misapprehended. His understanding was that the prized Arabian horses caught a contagious disease during the voyage and were buried at sea. In fact, though, most of the party of horses, camels, and entertainers did arrive at the Exposition. It was later, due to burgeoning financial straits of the Syrian group in Chicago, that the group sold the horses to well off American horse lovers. Abdullah did sail home to an-Nabk shortly after the Fair wound down. He remained there for about ten years during which time he and his wife had five children. Alan’s father, Albert, was his youngest. Not long after Albert was born, Abdullah returned alone to New York.

Judging from Abdullah’s written account of the voyage and the Fair in Kawkab Amirka, one gets the impression that he was assigned, or perhaps simply decided, to be the documenter of the Ottoman Empire’s participation in that Exposition. Alan’s account also revealed that after the Fair Abdullah “apparently started an Arabic language newspaper in Brooklyn.” Alan added that he could have tried to trace the history of Abdullah’s purported newspaper, but he did not, concluding, “In a funny way, the story is satisfying enough.”

Following up on Alan’s remark, I discovered that indeed, when Abdullah returned to New York around 1904, he attempted to build on his earlier work as a reporter. We first find him settled in Rochester in 1905 and identifying himself in the city censuses of 1905 and 1908 as a “salesman.” However, in 1908 Kawkab Amirka ceased publication, thus perhaps opening up opportunities for a new newspaper culturally and politically similar to it. For the next two censuses, Abdullah self-identified as an “editor,” rather than “salesman.”[2] In addition, there are indications, as yet unconfirmed, that he published in other Arabic-language newspapers. In any case, by 1912, he again resorted to identifying himself as “salesman.” This attempt to venture into journalism, rather than the Exposition visit, was, perhaps, the dream that Alan heard talk of in his youth, “that sounded great but somehow never quite worked out.” Alan’s grandfather had obligations to family in both Syria and America and doubtless, the sales business proved more likely to fulfill those obligations than a venture into journalism.

By the end of the second decade of the 20th century and the end of WWI, we find that Abdullah had settled in Jacksonville, Florida. In Jacksonville’s city surveys of businesses, he described himself as a “grocer man” or “butcher.” By then he was nearing sixty years old and I can only speculate why he moved to Jacksonville. Jacksonville, like New York, had an established Syrian community, but a warmer climate may have suited him better. He may also have had closer friends and relatives from the old country there. In addition to other Jabbours in the area, Abdullah’s wife was Hannah Nasrallah and, according to Alan, there were Nasrallahs in Jacksonville. When Abdullah applied for his first passport in 1920, it was Jacksonville native and kinsman Andrew K. Nasrallah, who worked in the wholesale cigar industry, who swore to Abdullah’s identity. Adding to the family-ties in the area, Abdullah’s mother-in-law was a Katibah and Alan remembered Katibahs among the Jacksonville kin as well.

ALBERT JABBOUR COMES TO AMERICA AND FINDS A WIFE

Alan told us that before the war, when Alan’s father, Albert, was a pre-teen, there was already talk about Albert joining his own father, Abdullah. Indeed, on April 8 1919, the year after World War I ended, Abdullah applied for a passport on which he indicated plans to meet his son in Egypt and visit a cousin in France.[3] Albert, who was about 19 when his father brought him to America, had different expectations of immigration.[4] Whereas Abdullah, had left behind a wife and children in an-Nabk and expected to return home, Albert arrived as a much younger and unmarried man with a father already established in the United States. In contrast to his father, Albert never returned to Syria, even for a visit. He became essential to Abdullah’s grocery business shortly after he arrived and, according to Alan,

My father never went back. He talked about it. It wasn’t that he didn’t want to, but he was a grocer and grocers of that older generation were strapped to their stores. They didn’t know how to get away. They didn’t know how to take a vacation.

Unlike Abdullah’s visit to America due to the excitement of the Chicago Exposition, Albert’s life trajectory changed due to the fallout of a global war on the “old country.” Albert had been old enough to start thinking of college when World War I broke out, but with that upheaval, everyone, as Alan put it, “stayed buttoned in place.” Alan’s dad, like so many other youths in the region, had to revise his plans. If not for WWI and the repercussions for the Ottoman Empire, Albert would have expected to attend the newly renamed American University in Beirut,[5] located some 110 miles southwest of an-Nabk on the Mediterranean coast. His slightly older cousin, Jibrail Jabbur,[6] of nearby Qaryatayn, Syria was able to attend.[7] However, by the time Albert was ready, Alan says, “There was a gigantic waiting list because of the war … three years or more.” In addition, Albert, like his father, Abdullah, may have possessed some wanderlust after hearing stories of Abdullah’s travels.[8] Albert, and presumably Abdullah, had the Middle Eastern facility with languages and Albert would have known some French, English, perhaps German, certainly Turkish, and of course Arabic. In anticipation of a voyage west, Albert may have honed his English and French language skills. Alan says of his father, “[H]e spoke English like a native. In that case, it means like a Deep South Jacksonville native. He talked just like everybody else. Well, he talked like me.”

Albert joined Abdullah helping him in the small, but growing, Jacksonville grocery and butcher business. Alan mentioned that the Jabbour men do not live long due to heart issues and Abdullah did not live very long after they returned to Jacksonville. While Alan, and Abdullah himself in his accounts in Kawkab Amirka, shared much about Abdullah’s life and travel to the United States, I still wish I could learn more about this intrepid grandfather.

ALBERT’S COURTSHIP STORY

When Mody Boatright, a Texas folklorist, put out his call in 1958[9] to folklorists to collect “an important source of living folklore”—the “family saga,” he was not interested in a “chronological history,” he wrote, but rather “individual stories with a variety of themes that preserve a family’s way of seeing itself in history.”[10] He sends us back to Martha Beckwith’s 1931 observation about folklore in general to support his assertion that sagas, “function in the emotional [emphasis mine] life of [us] folk.”[11] As a folklorist, I too focus on the lore component of a family saga; that is, the aesthetic, affective or performative dimensions of the stories—dimensions that attract anyone to a story, whether related to the storyteller or not.

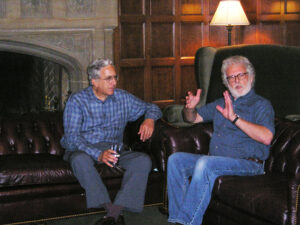

Over the 90-minute filmed interview with Alan, the interviewers being folklorists, and Alan also being a folklorist, we tended to veer toward the stories that were touching, humorous or adventurous. During the course of talking about Alan’s father and his wife, Irma Mae Williams, Pat Mullen, ethnographer par excellence, naturally asked, “Did they have a courtship story?”

Then, Pat and another folklore scholar, Barbara Lloyd, at that time Assistant Director of the Ohio State Folklore Center, along with Alan himself, commenced to draw out the affective dimensions of the story.[12] In response to Pat’s courtship question, Alan said,

Yes, actually. My mother told it. It was a lovely story, I think. My father had a little grocery store. This was on the north side of Jacksonville. Not the one I grew up in, which was a later and larger one. He had a small grocery store and my mother and her foster mother had moved to Jacksonville from Ocala. When they moved to Jacksonville, they took up residence in a kind of rooming house where they helped out with food service. . ..

Alan continued,

So, [one day] my mother went into the grocery store to get things that were needed for cooking. She was just a girl of fourteen or fifteen. She was really young. [Into the store came two young men] who made some sort of aggressive moves toward my mother and were sort of pestering her and frightened her. My father came from behind the counter and in effect chased them out of the store.

I remarked that Alan’s father became the young girl’s hero. She was as a maiden saved in a folktale, but in an every-day American setting, a grocery store. In this hero story, Albert saved the young girl not from a dragon or some other mythical beast, but from some ill-intentioned young men.[13] Pat then observed, “the courtship story . . . suggests . . . crossing of the cultural boundaries . . . through masculine behavior . . . standing up for her honor and protecting her. . . .” That chivalric masculine behavior was able to construct an early bond between a girl from rural northern Florida (a “Florida Cracker”[14]) and a young man, older and more “worldly,” from a mysterious place called Syria, standing up for her.

This discussion led us to discuss community reactions to this marriage between two people who were each, in different senses, outsiders in that community. In this case, one was a “cracker” and effectively an orphan, as Alan pointed out, and Albert was a Syrian stranger, considered a little exotic by some people in town who asked, “Is that…white?” Yet, he was able to win many of them over with a good deed. Alan told us that the relationship grew as his father started taking his lunches at the rooming house near the store where they lived and worked.[15]

Travel is an important motif in an immigration saga. Both Barbara Lloyd and Alan built on the hero dimension of the courtship story by invoking travel images. “So, your father in the courtship story, he rescued her in more than one way,” Barbara ventured. In response, Alan commented,

That’s a very good reading. … In many ways she was a waif of an orphan, or a little voice in her still said that to her. She was doing fine; she and my foster grandmother were making a life for themselves and doing very well at it, in effect re-inventing themselves. In a funny way, their journey was as far as my father’s journey.

In this conversation, he and Barbara collaborated to compare the different life journeys of Albert and Irma Mae— they theorized that a simple journey, in his mother’s case, from a rural area into town was also profound, as it was a bold, life-changing venture that, in a sense, was “as far as” his father’s journey from Syria. It would not be surprising if, in future telling of his immigration saga, Alan might have incorporated or even elaborated on this theme. Alan summed up his heritage, “I’m one of a small but vibrant number of people who are Syrian Crackers. There are a few of us out there. I’ve met a bunch of them.”

Pat’s initial eliciting of the courtship story encouraged an ongoing appreciation by the folklore audience of Alan’s father and a re-appreciation of his father by Alan. He attributed his early ability to interact with adults both to interactions with customers while working in the store with his father and, at least by high school, to his position as principal of the second violins in the Jacksonville symphony. By 12th grade, he was leading musicians much older than he was. Music became an important part of his life “very early and very deep,” he shared, and he was encouraged and supported in his music at home and at school. We learned that his father had played the oud (lute) back in Syria. Stringed instruments weave deeply into Arab as well as into southern cultures, whether rich or poor, urban or rural, or, in the case of the American south, whether black or white. Both childhood experiences, the grocery store work and the symphony participation, Alan summed up, “had a huge influence on my later life because in both cases it got me out of my immediate peer group and enabled me to live in the grownup world. Music enabled that and so did running a grocery store. When you . . . deal with all the clientele with all their demands and words and deeds, it teaches you a lot about life.”

Questions asked or comments made about Albert’s life by Alan’s folklore audience had led to an extended collaboration with Alan, in this case in appreciation of the quiet heroism of Alan’s dad. Speaking of his two childhood advantages led Alan to give another nod to his father’s care for his future. The one thing he was NOT allowed to do in the store was cut meat, “because [my father] had been around butchers all his life” and he knew most of them were missing a finger joint. “Grocery store is tough,” Alan said. “His vision of me was not the vision of a grocery store.”

Recall that earlier in the interview, Alan mentioned that Albert had missed attending college due to WWI and it was when our interview fell into a more conversational mode that we elicited from Alan, almost a eulogy for his father. Alan told us that his father “gave his life” to get him a fulfilling occupation, a sentiment commonly celebrated by the offspring of immigrant parents be it in poetry, novel or oral narratives like family immigration sagas. Earlier I ventured that the same consideration for family over self resulted in Abdullah, Alan’s grandfather, giving up his dream of establishing himself as an editor. His dream might have worked, but he had family to support thousands of miles away.

Family immigration sagas change over time; they are elaborated on, restricted, or changed depending on audience reactions and interactions. New motifs emerge. In the case offered here, the folklorists’ focus on life’s affecting dimensions and on folk community led to what I perceive as new foci in Alan’s family saga. Family sagas, including immigration sagas, are, after all, a fluid art form.

TO BE CONTINUED

This second blog focused on Alan’s father, Albert, how he got to America, his courtship, and his influence on Alan.

In the next blog, Alan considers how his upbringing was inflected by life in mid-20th century Jacksonville and by his parents’ marriage—the marriage between Irma Mae Williams, a girl from the rural south, and Albert Jabbour, a young man from Syria. As Alan noted, “People sometimes think of family history as . . . following one family line, but family history always starts with at least two branches and then four branches . . . and each generation beyond it.” How did Alan see the merging of those two traditions, two cultures, affecting his own story of his life choices as a young man?

Notes

[1] Translations from Kawkab Amirka were made by Christopher Hemmig, PhD and transcriptions of the 90 minute film “A Cultured Man” by Folklorist Mike Luster, PhD

[2] Abdalah [sic] Jabbour identified himself as a “salesman” in the 1905, 1908, 1912, 1913 and 1916 Rochester city censuses and in 1917 seems to have moved to Utica. In the 1910 and 1911 Rochester censuses, he identifies as an editor. https://roccitylibrary.org/digital-collections/rochester-city-directories/rochester-city-directories-by-decade/

[3] Perhaps due to immigration concerns, Abdullah does not say that he is bringing Albert all the way to America. Family lore given to us by Alan contained mention of the visit of Abdullah and Albert to post WWI France. There are also hints in United States military documents that a Jabbour “cousin” was demobbed there.

[4] I am tentative about these dates for in the old records there are discrepancies as to dates of birth, death, arrivals in the U.S. and so on.

[5]The Syrian Protestant College, founded in 1866 changed its name to American University of Beirut in 1920 after WWI. Perhaps of interest, just a year previously the Kerr family’s reverse odyssey commenced as Stanley Kerr and his soon to be wife, Elsa Reckman Kerr, arrived in Aleppo as relief work volunteers and by 1925 began serving on the faculty of AUB, where they remained for forty years. Their children grew up there and one son, Malcom Kerr, for many years a professor at UCLA, went back to Beirut as President of AUB. He was gunned down in 1984. (His spouse, Ann Zwicker Kerr, is author of Come with Me from Lebanon: An American Family Odyssey. Introduction by Albert Hourani. Syracuse NY: Syracuse University Press 1994. Steve Kerr of basketball fame is one of their four children.)

[6] Jibrail S. Jabbur, The Bedouins and the Desert: Aspects of Nomadic Life in the Arab East, trans. Lawrence I. Conrad, ed. Suhayl J. Jabbur and Lawrence I. New York: SUNY Press 1995.

[7] Jibrail later married Albert’s sister, Abdullah’s daughter, Asma.

[8] I sometimes wonder if youths in some families take extended travel for granted due to hearing stories of traveling relatives from an early age.

[9] 1958. Boatright, Mody C. “The Family Saga” IN The Family Saga and Other Phases of American Folklore. Mody C. Boatright, Robert B. Downs and John T. Flanagan. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. pp. 1-19.

[10] Boatright himself hesitated at first to use the label “saga” for it at the time referred to a very particular tale type and genre—“heroic poems of Ireland or Iceland or the North European continent dealing with battles and trials of strength and …genealogies of heroes.” (p.1) Boatright characterized American Family sagas as consisting of an array of forms and motifs borrowed from various media and genres. However, in both European and American definitions, sagas depend on an oral component, either an oral narrative, or a written narrative that relies on the quoted speech of an oral raconteur. A second similarity would be that in each case a saga is expected to cover a broad swath of time and depends on shared genealogical roots.

[11] 1931. Beckwith, Martha Warren. Folklore in America: Its Scope and Method. Poughkeepsie New York: Vassar College. Quote is from p. 2.

[12] This interlude in the recording is a very good example of how much audiences influence an interview. As all of us were folklorists, it is not surprising that right away we all, in addition to Alan, joined in unpacking and analyzing his story—with feeling.

[13] My name, Sabra, comes from an old tale of an Egyptian (sometimes Libyan) princess saved from a dragon by St. George. c.f. the pre-Raphaelite paintings of Raphael, Tintoretto, or later, Edward Burne-Jones.

[14] Alan said, “There’s an area in south Georgia and north Florida where people call themselves ‘Crackers.’ There’s a much wider area where people call other people ‘crackers…’” Later he added, “You could draw a line around the area where people call themselves crackers.” Pat said, “And your mother would be one of them.” Alan added, “And therefore I am one of them because if your mother tells you you’re a cracker, you’re a cracker!”

[15] Jacksonville took pride in its music culture and for musicians it might be of interest to know that Abdullah’s presence in Jacksonville overlapped with that of Ruth Crawford Seeger in her teenaged years, later to be wife of Charles Seeger, stepmother to Pete Seeger, and mother of Peggy and Mike Seeger, among others. After her father, a well-known Methodist minister died, her mother, Clara Crawford, fell on hard times and bought a house that she turned into a boarding house. It might have been similar to the boarding house where Alan’s mother and foster-grandmother had lived and worked.

- Categories: