Letters from Afar: New Khayrallah Center collection of letters from West Africa to Lebanon

Introduction

In 1936 Nadim Attallah, a Lebanese immigrant living in Conakry, Guinea (West Africa), wrote an exasperated and desperate letter to his father, Maronite Rev. Tobia Attallah of Bayt Shabab village . He chided him: “I am astounded that after the hundreds of letters that I have sent you, I have yet to receive one from you…how long will you hold this grudge against me?” Two years later Nadim’s brother, Krouger Attallah—also living in Conakry— penned a far more strident letter. He threatened their father: “This will be the last missive from me if I do not receive a letter from you.”

Such strained relations are certainly ever present in families regardless of the circumstances. But the yawning physical distance brought about by late 19th and early 20th century Lebanese migration heightened emotional stress for families strewn across continents. Personal slights, perceptions of preferential treatment, and questions about money and property were magnified by long silences, as abbreviated letters wended their postal way across thousands of miles and over weeks.

More critically, migration created a profound gap of experiences. Those who emigrated felt that their toil, loneliness, fear and reality of failure, uncertainty of environment, challenges of new languages and customs, and utter fatigue went unappreciated by those who remained in Lebanon. Those who stayed were left carrying the burden of maintaining a home in difficult circumstances which—at least from their perspective—immigrants had escaped, and may have felt humiliatingly dependent on the far-too-infrequent largesse of departed relatives.

Driving a bigger wedge still is the reality that family members—separated by migration—were more prone to go their separate ways culturally. Émigrés spent years, and sometimes lifetimes, in different linguistic and social environments that changed them in both small and large ways. Simultaneously, being “Lebanese” in Lebanon morphed beyond the memories of immigrants, who nostalgically held on to a past that no longer existed for those they left behind.

These realities and tensions are rendered starkly visible in a collection of immigrant letters newly acquired by the Khayrallah Center. The correspondences started in 1914 and stretched across three subsequent decades, and were dispatched primarily from West Africa with a few letters sent from Brazil. They chronicle the journeys and struggles of three of Father Tobia Attallah’s children: Krouger, Nadim and As’ad Attallah, and their relationship to him, to each other, to their new homes and to Lebanon.

What emerges from reading these letters as they unfold over time, are the trials and tribulations of immigration. Mixed with some success, to be sure, was a good measure of pain and disillusion. This observation may appear rather prosaic and self-evident. But, in fact, it adds a much-needed tonic to the far too frequent gloss applied to immigration stories of the Lebanese that sanitizes them of woes, and renders them replete with unmitigated success. It humanizes immigrants and those who remained in Lebanon beyond the cartoonish two-dimensionality of popular mythologies that continue to be traded even today. (See this and this essay for greater discussion of an example of these myths). A quick tour of the Attallah letters shows some of these intertwined and messy moments of tender emotions and hurt feeling across three decades. And lest one is tempted to think these are exceptional, a quick glance through the Ellis Collection, another of the Khayrallah Center’s collection of letters, will reveal similar tropes.

Immigration

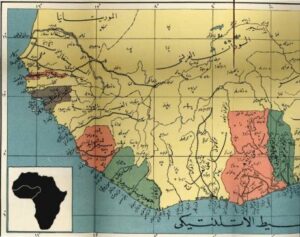

Immigration to Sub-Saharan Africa from the Eastern Mediterranean started somewhere around the early 1880s. More specifically, as Rashid Baydoun wrote in his 1938 book Nahnu fi Arfiqyya (We are in Africa), [1]: “in 1892 four or five Lebanese immigrants, ages between 20 and 22” arrived in West Africa and settled in the cities of Saint Louis in Senegal, and Conakry in Guinea.[2] In 1900 the number of immigrants to West Africa had gone up to a little over 400, and by the time Baydoun was touring around the various communities, in the mid 1930s, it had increased dramatically to 10,000 immigrants. Of those, around 1,000 came from the village of Bayt Shabab, the home of the Attallah family. In Guinea, the first immigrant—as told to Baydoun—was from Bayt Shabab, a man by the name of Rashid Bitar, who was shipwrecked in Conakry, the capital, in 1893. From that point forward, the number of immigrants increased steadily until it reached around 1,600 by 1938.

What drew Lebanese immigrants to West Africa was the same motivation that took others across the globe: the hope and dream of amassing a measure of wealth, and returning home to enjoy better quality of life and higher social status. For the most part early immigrants peddled with the qashé, selling beads, fans, and bracelets to the Fula communities in the hinterlands. However, they quickly shifted to trading in natural rubber, and undercutting the mainly French and German trading companies that had dominated that field. The competition they offered (by buying directly and at higher prices from the Guinean producers) led to continuing attempts on the part of European traders to prohibit these immigrants from the rubber trade, and to block any future immigration. These efforts failed because the French colonial administration rejected controls over “free” trade and the ad hoc coalition rarely maintained cohesion. By 1938 Lebanese immigrants reportedly owned 90% of the stores in Conakry, and 25% of all buildings in the town. In addition, some extended their business into banana groves in the hinterlands of Guinea, owning a total of 25% of those commercial farms.

But as Dr. Andrew Arsan notes in his brilliant book about Lebanese immigration to West Africa, Interlopers of Empire, this pursuit of wealth did not always end in financial success. He documents the myriad bankruptcies that plagued the community, where immigrants like Salim Salqa and Michel Abdallah worked in multiple jobs searching for elusive financial success. The difficult lives encountered were also a constant theme. For example, French author André Arcin, wrote in his 1907 book on French Guinea that Lebanese immigrants: “‘lived far more miserably than many blacks in huts … where not a single European could resist the climate.”[3] His observation was deeply colored by imperial notions of who could withstand extreme heat and reciprocally perform hard labor.[4] But underneath its imperial façade, Arcin’s observation still revealed the class dispersion of Lebanese immigrants and the kinds of work that they did. Similarly, Rashid Beydoun noted in his book: “I saw in the deserts of Senegal some of our immigrants living and working in small huts with sheet metal roofs, with a temperature that exceed forty [Celsius, or 104F].”

The Attallah Letters

The story of the Attallah brothers, as told in their letters, reflects many of these themes. It is not quite certain when and where they started their lives as immigrants, but what seems certain is that Krouger Attallah was the first of the three to arrive in West Africa, with his first extant letter dated December 14, 1926 and written on the letterhead of the Chaya Frères Lebanese merchant house. (It is very likely that he was working for them in their Bissikrima branch.) In that letter, Krouger wrote that their brother As’ad seems to be doing well in his visit to their sister and brother in law in Brazil, but that he might come to Guinea the following year. At that time, Nadim—about whom Krouger complained for not writing—was still studying in Lebanon. In that same letter, Krouger implored his father: “do not let Nadim become lax in his studies, which is the only guarantee of his success in these hot climes.” In the next sentence, Krouger noted his surprise at the fact that his father had not received the “money I sent you.”

And so it went for 200 some letters: money was an ever present topic of concern. In 1928, while Nadim the youngest brother was still in Lebanon, Krouger implored his brother to stay in the “country” [Lebanon], and not to worry about money, because “you will receive money to cover your living expenses.” In 1932 Krouger told his father that As’ad was too embarrassed to write Tobia because he did not have any money to send. A year later, in 1933, As’ad wrote his father to assure him that “every time I get 100 French Francs I send them to you.”

Years later, after Krouger had returned to Bayt Shabab, it was Nadim’s turn to assure his oldest brother that money was sent to him. Nadim wrote in September 1948: “I have written you from Conakry [to Bayt Shabab where Krouger had retired] and told you that I had sent you 12,000 French Francs through the bank, and 50,000 [Francs] to Marseilles…25,000 from Shikrallah and 25,000 from me.” A year later Krouger received a letter from his cousin Shikrallah in Conakry, informing him that Nadim had run the company into the ground accumulating more than one million Francs in debts to other Lebanese and non-Lebanese merchants, and subsequently had lost everything. The subtext was that no more money would be dispatched to Krouger.

Beyond money, the Attallah brothers regularly described (directly or indirectly) the hardships they faced in West Africa. In 1929 Krouger wrote his father that he was recovering from a bout of illness that kept him bed-ridden for weeks, and that he will leave Guinea permanently and retire to Lebanon “with money [he saved] that should be enough, around 750 Syrian liras.” Eight years later, in 1937, Krouger wrote with an air of absolute confidence that Asa’ad Makhoul (another villager from Bayt Shabab) should not have brought his wife and children to “this country especially…before he finds out whether he can tolerate its bad climate.”

The pain of distance and loneliness speckled these letters. Aside from chiding their father (or being chided by him) for lack of communication, both Nadim and Krouger wrote frequently about their ache to leave Guinea and see home. For example, shortly after his arrival in Kandia (a town in the hinterlands of Guinea) in 1931, Nadim wrote his father: “I have not forgotten what happened to Emily [who was very upset by his departure] when I left to go to Beirut to emigrate, but as you say we have to struggle to make a living.” A couple of years before, Nadim wrote wistfully about the Christmas holidays: “Last year I was celebrating amongst you [in Bat Shabab] and this year I celebrate [by myself] in the land of estrangement.” Krouger reiterated these same feelings in various letters, always asking his father to “put my mind at ease about you and my sisters.” This concern for even a morsel of news to placate the anxieties of the immigrant brothers (and in return, their family in Lebanon) was a recurring plea. While it may appear formulaic at times, far more often it was driven by the real anguish of separation, and the desperate need to maintain emotional relevance in each other’s lives. The frequency of the letters and the persistence of these themes was one of the few ways to remain a family, especially when their ties were stretched to the breaking point by migration.

Conclusion

In the end, and despite these efforts, the family was battered by the stresses of migration. As’ad, apparently the black sheep of the family, wrote only a handful of letters, and all mention of him stopped after 1930. He seemed never to settle on a profitable career whether in Brazil or later in Guinea, and was always worried of being a disappointment to his father. While Nadim wrote more (but still far less than Krouger) it is not clear what happened to him after he went bankrupt in 1949; we are not certain whether he returned to Lebanon or lived out the rest of his life in Guinea. Krouger is the only one of the three brothers who certainly returned to Lebanon. In his last letter to his father Tobia, dated September 14, 1946 from Conakry, he wrote: “This is the last letter I write you from Africa…Joseph [his son] and I have secured seats on a ship, and we will leave the 19th of this month to see the compassionate father who I have not seen in 21 years…Please gather a lot of wood and coal for heating because we will be arriving at the beginning of winter.”

[1] Rashid Beydoun (1889 – 1971) was a prominent Shi’ite intellectual and political leader in Lebanon. In 1938 he led a delegation from the ‘Amili Philanthropic Organization on a tour of the immigrant communities in Africa to collect donations to establish a school for teaching Shi’ite youth in Beirut. The book, Nahnu fi Afriqyya, was a chronicle of that tour. While factual for the most part is its description of the various African nations, its approach to the indigenous African population can be gathered from the dedication: “To those [immigrants] who lose their youth in the hell of the black continent and its twisted jungles.”

[2] Rashid Beydoun, Nahnu fi Afriqyya, p. 191.

[3] André Racin, La Guinée Française: Races, Religions, Coutumes, Production, Commerce, Paris: Augustin Challavel, 1907, pp. vi, 93, 100.

[4] Ikuko Asaka, Tropical Freedom: Climate, Settler Colonialism, and Black Exclusion in the Age of Emancipation (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017).

- Categories: