Alan Jabbour, “A Cultured Man”: Foodways, Music, and Syria Dreamin’

This blog was written by Folklorist, Sabra Webber. Webber is a professor emerita at The Ohio State University in the Department of Comparative Studies and the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures. She visited the Khayrallah Center in the Summer of 2018 while researching her former colleague and friend Alan Jabbour. She wishes to thank Ruth Ann Skaff and Marjorie Stevens for their research assistance. This is the third installment of three blogs about Jabbour’s immigration saga.

You know growing up in the South in the sixties there was a revolution going on, we were all part of it, and it forces everybody to think about culture a lot. That’s another reason maybe that I got interested in folklore because when you’re a Southerner growing up in that world that’s changing you’re forced to think about what to preserve and what to pitch out and culture all of a sudden comes up to the conscious level. It’s not just what you do but you’ve got to think about everything you do because everything is under evaluation.

Alan Jabbour

As we five folklorists conversed with Alan Jabbour about his family immigration saga over the course of ninety minutes, he guided us from stories of his grandfather’s and then father’s experiences as adult immigrants to his own life as the first of his family to be born and to spend his childhood in America. We drifted toward exchanging ideas about what ties families to their cultures including “what to preserve and what to pitch out” and how Alan’s family culture(s) might have affected the choices he made in life. The subject of food came up—food in culture and food as culture, whether perceived as Syrian, Southeastern American, or more specifically food in Alan’s own family in Jacksonville, or some melding of the three. What folklorists call “foodways,” stories about or customs and beliefs central to a community’s food habits, are not unusual topics in immigration sagas as we saw with the banana and olive boat stories in the first blog—traveling food and traveling people.

I’VE LOST MY CULTURE!

. . . the family was very conscious—as many Syrian families here were—of maintaining culture.

Alan Jabbour

As we questioned Alan about his foodways experience in Jacksonville, a natural progression after his account of the mixed marriage between his parents who were both in the food business, Alan suddenly said, “I won’t say anything about Arab Americans generally or even Syrians generally or Lebanese, but it was certainly true of my family that people were extraordinarily fussy about food. Food had to be just such a way. It couldn’t be any other way.” He continued,

Even your leben.(1) Your leben couldn’t be any leben from anywhere. It had to be from your home village or it wasn’t right. So, if . . . you make your leben and something goes bad then you’ve lost your culture. . . . You’ve lost your [starter] culture now what are you going to do? You can’t just go get it from somebody [in the Jacksonville Arab community] who is not from your village. So you write back home to your home village and you say, I’ve lost my culture, and . . . they take a plain white handkerchief and they dip it in the leben and then they hang it up and dry it in the sun. And then they fold it up, put it into an envelope and mail it to America, and it’s enough to start the culture.

He concluded, “That trick was one of these great cultural tricks that shows how those worlds are linked up. They’re linked up by that handkerchief being mailed across the ocean.” (2) Alan demonstrated the process as he spoke. He pulled a crisp white handkerchief out of his pocket, unfolded it, mimicked dipping it in leben, and then refolded it bound for an envelope and a long journey.

The play on the word “culture” is powerful here since drawing on the culture needed to start leben evokes the longing immigrants have not only for material aspects of their home culture, as we will see later with the coffee story, but specifically for the communal setting and practices of one small Syrian town. Thus, the word for one basic ingredient, the starter culture for the leben, is also meaningful in a much larger sense. (3)

Many have written about how food, through the five senses, evokes memories—a familiar smell of cinnamon, the taste of hot pepper seasoning, the texture of rice cooked “properly” according to the practices of a town in Syria, China, Iran, or Mexico. Catching sight of the implements used to produce the food is also reminiscent of time past and perhaps conjures memories of the old country. The kesskess used for steaming couscous or the mortar and pestle are no longer used as often but glimpsing one or the other (or hearing a mortar and pestle clinking away) awakens memories of not only the food, but the loved ones who made the food in days gone by.

SYRIAN CRACKERS

So! I’m one of a small but vibrant number of people who are Syrian Crackers. There are a few of us out there.

Alan Jabbour

When two families marry, they negotiate new foodways—especially when the bride and groom, as in this case, are perceived as coming from very different worlds. However, as we saw in Blog II, even Alan’s parents’ courtship story revolved around food. Both of his parents, in one way or another, were in the food business at the time that they met and were from cultures that tended to be, as Alan said, “fussy about food.” Albert’s little store (4) was a place where the girl who later became his wife, and her foster mother shopped for food for the nearby boarding house where they lived and cooked for the other boarders. And as time went by, Albert sometimes lunched at that boarding house where, naturally, the food was Southern. (5)

When Alan explained the marriage of a “Florida Cracker” and a Syrian, he said, “What I’m conscious of being is two things and not one thing. So my little story about being Syrian Cracker is fun to joke about but it’s joking on the strain because that’s conveying that I see both sides of my identity and I don’t see one as the real me and the other as just some echo or vestige. So, I do see myself in that way as multicultural.” In negotiating a new set of family traditions, Alan’s parents drew on foodways that were brought from two, already highly complex, sets of practices. In our filmed interview, Patrick Mullen related to Alan’s parents’ “mixed” marriage as his wife’s family is steeped in another Mediterranean culture that takes its foodways seriously—Italian culture. However, Patrick is still Texan at heart with a very different and robust eating tradition, and he would roll out Beaumont Texas barbeque to the delight of his Columbus colleagues and students.

NEGOTIATING KIBBEH

When I speculated that Alan’s mother did not cook Syrian food, Alan corrected me saying, “She learned from my father’s female relatives, which had to have been a baptism by fire.” I realized that this addition to her cooking repertoire would seem normal for a woman who from girlhood was involved in preparing food for a living under the guidance of her foster mother. Alan continued, “We regularly had . . . stuffed grape leaves and stuffed squash and we regularly had kibbeh and we regularly had rice sort of Arabic [sic] style. It was a style that was more inland Syrian style than the more Mediterranean Lebanese style.” And he told us,

At a certain point it became part of [my mother’s] cuisine, not just “their” cuisine that she was reproducing. As it became her cuisine, she started making choices . . . based on her sense of how she liked the household. For example, the classic example, the old world way at least in our family of making kibbeh was much longer cooked and drier, but my mother thought it was much nicer moist and not so dried out, and so she very consciously Americanized that. It’s not as if she unconsciously changed it. She knew just what she was doing. And that’s the way I like kibbeh to this day.

Barbara Lloyd then asked if Alan’s mother made Southern food and Alan said, “Deep South style food. So, our cuisine was Deep South. Our cuisine was Syrian Cracker. That’s how we ate. We ate everything from okra to rice. Rice was a staple in our house. Actually rice was a staple for both sides. From my mother’s side as a rural Deep South person and from my father’s side as a Syrian. So double reinforcement.”

THE ART OF COFFEE

Near the end of our interview, Alan fell into impersonating his Aunt Lilly as he related a story of a coffee clash in the family. He repeated what he said earlier about his family in Jacksonville being “very conscious” of maintaining culture through foodways. Then he went on to say that,

In a funny way also [they] debated it forever, constant arguments about food. . . . I can remember a fight at one of my cousin’s houses when we were young adults. . . . A big debate that got sort of nasty broke out about how to make coffee. Aunt Lilly, the maiden aunt, was still living back in the old country, back in the old home place. She was the last inhabitant of the old home place. Aunt Lilly was there and listened to this debate about which coffee to use and how to percolate it and people were making their own coffee and asking us, their guests, to say which was better. (6)

Alan became quite animated during this story, reliving it, almost acting it out, and in the process lighting our imaginations too. We could almost see the hubbub of folks running back and forth to the kitchen “performing” their own coffee making and then foisting the result on the guests. At the climax of his story, Alan dramatically proclaimed,

So finally, Aunt Lilly rises from the table and she says, “You’re debating about how to make your coffee and yet there over your fireplace are the implements for the proper making of coffee, the separate pot you must boil the coffee in and then pour it in the next pot, but you have turned them into implements that you use for decorations over your fireplace instead of using them for the coffee like you should’ve.” She thereby trumped the whole gang and made her declamations. Aunt Lilly was the rock of tradition. (7)

It seems that Aunt Lilly was finally, as Alan tells the story, the only one who could make coffee “correctly,” and of course “correctly” meant how it was expected to be served in an-Nabk.

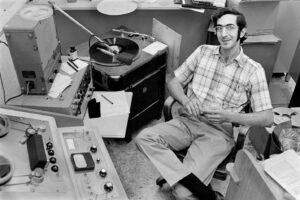

SYRIAN CRACKER MUSIC? A FOLKLORIST AND A FIDDLER

Moving from cookery to music, most artists, whether masters of cooking or of musical traditions (in Alan’s case the violin and the fiddle), are not interested in being tied to labels but rather in performing music or cookery for a community that can appreciate their work. “Community” might be composed of other cooks or musicians or of a larger community of family, neighbors, and friends. (8) Alan chose the latter; the “real thing” to him it seems was discovering music amidst the hustle and bustle of everyday life in everyday settings rather than the formality of the concert hall.

But the concert hall was where he started and stayed for most of his youth. Pat observed in regard to Alan’s introduction as a seven-year-old to violin in school and music camp, “It sounds like music just became an important part of your life.” And Alan replied, “Very early and very deep.” He adds that he was playing professionally by high school. Quite a bit can be found in other publications concerning Alan’s love of bowed string instruments, first the violin and later the fiddle, his virtuosity, and his field research as an adult into fiddlers and fiddling, so I will not dwell on it here. However, in his conversation with us folklorists, all music lovers though not musicians, we together turned to pondering ways in which Alan’s Syrian family heritage influenced his talents, chosen research, and performance trajectory as he moved from the formality of violin to fiddle and folklore.

Alan’s father played a classical string instrument, the oud, (9) before he left Syria, and we saw in the last blog that he valued Alan’s talent and protected it. Despite Alan’s pride in the life lessons he learned working in the grocery store, his father would not let him “cut meat” since most butchers were “missing a joint.” While still in high school and working in the grocery store, he was already playing with the Jacksonville Symphony. Up until the end of his graduation from the University of Miami in 1963, where he majored in English, he continued to play violin with the University’s symphony orchestra. (10)

In our conversation with Alan about his musical career, Alan remarked that he “set aside” the violin after he earned his BA, as he no longer had the intention of being a professional violinist. Pat made reference to a recent conversation that he had had with Alan and folklorist Dorothy Noyes. (11) Pat said, “We talked . . . in Dorry’s kitchen that night [about] that whole transition from classical music to old-time music, from violin to fiddle,” and how that happened.

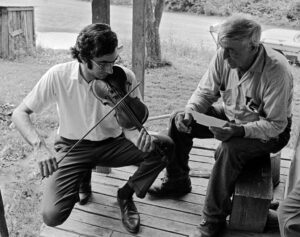

From violin to fiddlers and fiddling, (12) and from written literature to oral tradition was not a planned progression. Although he had interest in folk music, popular in the late fifties and sixties, neither fiddling, nor folklore per se, were on the horizon when he distanced himself from violin culture. That quickly changed after he moved to Duke University to pursue a graduate degree in medieval studies. Upon hearing a fiddle in a course on balladry during his first year as a graduate student at Duke, he felt he had discovered the “real thing.” (13) “I thought,” he told us, “this is what I want to learn about.”

I wondered what Alan’s father would have thought of this transition. String instruments were and are central to the many types of Arab music, from what would be considered classical urban music, of the sort he played on the oud, to folk or old-time music. The equivalent of old-time music bowed on string instruments would have been known to him as well including the rebab, a simpler, more portable string instrument that can, like the fiddle in North America, be found in both rural and urban arenas and formal and informal settings despite its reputation as a country instrument. (14) Obviously, as in the Arab world, old-time music in America might be enjoyed in towns or cities and classical music in the countryside. However, violins tend to evoke ideas of concert hall performances, formal wear and formal settings, and years of training in music theory, whereas thoughts of fiddles turn to more impromptu or informal performances in natural settings played on less “precious” instruments by performers who master their art “apprenticeship style” while spending time in the company of more accomplished players. (15)

What inspired Alan after his already distinguished career as a young violinist to abandon the formality of the orchestra and concert hall venues for the very different world of old-time fiddling found in the Appalachian Mountains where a concert stage might be the cargo bed of a pickup truck or a front porch? After all, there is an assumed hierarchy between the violin and the fiddle with its more often folk, community, and apprentice-based aesthetic. Alan firmly contextualized his folkloristic and, in his case, specifically ethnomusicological inclinations by referencing his grandparents. He told us, “I sometimes wonder . . . whether my love of folklore isn’t a kind of quest for my grandparents. . . . I only knew about them through their being invoked in oral family history.” Furthermore, family heritage featured the mountains of Syria, which perhaps impressed him and other Syrians in contrast to Florida, the flattest state in the nation.

SYRIA DREAMIN’

My grandfather came to America from Syria and had dreams. My father followed him and joined him in this country. No matter where you are from, your family storytelling creates a felt connection between your past and your present life in America. It’s curious that my father was an immigrant, and I ended up . . . attentive . . . to certain cultural traditions here. Henry Reed was first generation, too. (16) His father came . . . from Ireland to America. (17)

Alan Jabbour

Alan’s emotional connection to his Syrian heritage comes primarily from stories his father recounted and from spending time in Jacksonville with kin and connections from Syria. Those stories were only of a Syrian childhood and youth for Alan’s father, who was only nineteen when he arrived in Jacksonville, never returned to Syria. It seemed that Albert’s nostalgia for the home of his youth and his family affected Alan. Whimsically, Alan remarked, “I’m a hopeless romantic. I want to go up in the mountains with some sheep like my father did when he was a kid. He actually shepherded one summer. Went up with the sheep into the mountains. That would be fun to do.” Somehow with that comment I could not help thinking of the nature side of Alan, the city kid. Perhaps that was another side of his passion for locating older fiddlers and their families and communities in the hills and dales of Virginia, North Carolina, and West Virginia, among other places. Furthermore, he was drawn to Arabic script, watching over his father’s shoulder as Albert wrote to his mother and later his sister, Lilly. Musical notation might have seemed like a similarly alluringly mysterious means of communication in his seven-year-old mind when he was first introduced to the violin.

As folklorists, we, who were peppering this “poor lad” with our questions, as Alan put it, could not help wondering about his love of folklore and folk music and of those communities where that music was nurtured. Near the end of our conversation/interview he said,

[O]n the Arab American side I come from a line of people who are both profoundly attached to and oddly displaced from their culture and a long line of people who have a history in an area where cultures are constantly crisscrossing, of both maintaining their culture and being closely observant of the cultures of others. And I have this uncle who wrote this book on the Bedouins of the desert so, you know, maybe cultural observation ran in the family. (18)

Alan concluded,

I’ve never been to Syria. Syria exists in my imagination through these stories of ours. So, there’s a Syria family cultural memory that I maintain. Whether it’s memory or imagination or some combination of the two I can’t know. It’s very present in me. I feel the place and yet I’ve never been there. You can feel a place with some strength and yet have never set foot there.

Notes

- Mai Nguyen, “International Variations of Yogurt: A Cultural Exploration of Milk,” Discover Magazine, June 30, 2014, https://www.discovermagazine.com/health/international-variations-of-yogurt-a-cultural-exploration-of-milk

- Later I heard and read similar accounts of important emotional linkages to the home village maintained around foodways. A cook in Beirut shared on her food blog that the leaves she needs to make her stuffed grape leaves must come from her village near the Israeli border, a dangerous setting. Still, this cook had to find a way to obtain those leaves—even Beirut grape leaves would not do. https://www.maureenabood.com/lebanese-grape-leaf-rolls-a-taste-of-dier-mimas/

- This play on two uses of the word “culture” is especially apt as the organisms that make up a certain leben taste must not be allowed to die. This belief in the localness and heritage qualities of yogurt culture seems something like assessment of sourdough bread cultures. San Francisco natives, like me, are sure that their bread culture cannot be replicated elsewhere. Well, at least some of us are sure of that. For as long as the yogurt bacteria from an-Nabk lives on in Jacksonville, something significant concerning an-Nabk stays alive in the Nabki descendants’ new world home.

- Alan explained, “My father had a little grocery store. This was on the north side of Jacksonville. Not the one I grew up in, which was a later and larger one.”

- Alan told us, “My mother was named Irma May Williams and was born and grew up in rural north Florida and she’s of that class of people in north Florida who call themselves ‘Crackers.’ It refers to rural basically poor whites. And so my mother was a rural white, a Florida cracker. There’s a much wider area where people call other people ‘crackers.’”

- Aunt Lilly (b. 1898) was Albert’s older sibling who, if Alan was a young man in Jacksonville, on this visit must have been in her sixties. She was the last Jabbour except for distant relatives to be living still at that time in an-Nabk, in the family home.

- This hit home with me and Pat during our interview with Alan because we taught a course on “Folk Art and Material Culture” in which we assigned Alice Walker’s short story “Everyday Use.” In that story, one daughter who had left her country home to go off to New York City, comes home for a quick visit largely, it seems, to make off with previously scorned homemade quilts, a hand-carved butter churn, and so on, items that she had discovered are admired in the city. Rather than being put to everyday use, they are destined to be displayed on her apartment walls, as Alan’s Jacksonville relatives displayed Syrian coffee implements. What was once common, became rare in a new context, be it Jacksonville or New York City.

- Sabra J. Webber Folklore Unbound (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, 2015), folk groups/communities pp. 72, 78-83, 111, 84-86, 114.

- Brandon Acker, “Introducing: The Arabic [sic] Oud,” YouTube, March 9, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KA5VdzRHh-U.

- With gratitude to Ms. Amy Strickland, Music Librarian and Assistant Head of the Marta and Austin Weeks Music Library at the University of Miami, for her efficient and thorough assistance with information about Alan’s undergraduate career at the University.

- Dorothy Noyes is another folklore colleague at Ohio State, past president of the American Folklore Society.

- Gordon Swift, “Learn the Difference Between Violin and Fiddle,” Instruments, Bows, and Gear (blog), Strings Magazine, March 1, 2006, https://stringsmagazine.com/learn-the-difference-between-violin-and-fiddle/.

- Interestingly, the professor who played the fiddle tunes for the balladry seminar was an immigrant, Holger Nygard, whose parents, from the Swedish-speaking area of Finland, first came to Canada when Nygard was nine years old. Like Alan, he played the violin in his youth. Dr. Nygard was a much beloved and distinguished professor at Duke University for most of his scholarly career and met Alan in 1963.

- Professor Dwight Reynolds, while conducting research for his dissertation, apprenticed himself to a rebab player in an Egyptian village. Dwight Reynolds, Heroic Poets, Poetic Heroes: The Ethnography of Performance in an Arabic Epic Oral Tradition (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1995). The practice is intense either way. In an example of reverse snobbery, the leader of a New Orleans jazz band when asked if any of his players read music replied, “I think a couple of ‘em do but it don’t hurt their playin’ any.”

- The plus side of an apprenticeship model from a folklorist’s perspective is that when Irma Mae, Alan’s mother, mastered Arab cooking by cooking with Syrian American cooks or when folklorist Dwight Reynolds mastered the Egyptian rabab playing with artists in an Egyptian village, they become potential members of much more diverse communities.

- “Henry Reed (musician),” Wikipedia, last modified October 4, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Reed_(musician)

- Catherine O’Neill Grace, “Alan Jabbour A.M. ’66, Ph.D. ’68: Striking up the Fiddle,” Duke Magazine, June 1, 2007, https://alumni.duke.edu/magazine/articles/alan-jabbour-am-66-phd-68.

- Jibrail S. Jabbur, mentioned in “The Second Jabbour Immigrant: Albert Jabbour and His Courtship Story,” (https://lebanesestudies.news.chass.ncsu.edu/2020/02/26/the-second-jabbour/) was author of The Bedouins and the Desert: Aspects of Nomadic Life in the Arab East (New York: State University of New York Press, 1995). Notice that the transliterated spelling of جبور varies.

- Categories: