Summers of Promises and Disappointments

This past summer (2022) around one million Lebanese immigrants visited Lebanon. Their arrival was awaited with great anticipation by many in Lebanon. Aside from long-delayed and much-needed reunions with families and friends, their return was expected to bring a desperately needed infusion of “fresh dollars” into the Lebanese economy. From hotels and cars, to shopping and entertainment, these returned immigrants were expected to spend an estimated $3-4 billion dollars over the course of the summer. While this will not provide a permanent solution to Lebanon’s financial crisis, or solve its political problems, it will bring some measure of relief to elements of the local economy. It was also hoped that their arrival will bring a psychological breath of fresh air; a welcome distraction from the unrelenting crises that have afflicted the Lebanese for the past decade.

Or so the narrative went. The reality is that this summer’s return migration highlights a warped relationship between Lebanon and its diaspora. As the majority of the country is mired in poverty–with some unable to even feed their families–well-off immigrants posted Instagram images of themselves living a bacchanal life of feasting and partying. The Lebanese Ministry of Tourism, seeking to encourage a summer return, flooded social media with photoshopped images of pristine pastoral life, abundant tables laden with food, and throbbing nightlife. No where was there any reference to the dilapidated infrastructure (brought about by political corruption) that cannot even sustain Lebanon’s population, let alone a million visitors. Garbage, pollution, insufficient fuel for cooking or driving, severely limited electricity, skyrocketing costs, and myriad other infuriating and humiliating daily experiences are swept aside to sell a mythological Lebanon that only exists for the top 1% of the country. The abject needs of so many are simply photoshopped out as inconsequential and inconvenient truths.

Although certainly disturbing in its willful elision, this artifice of a facade is even more problematic because it does nothing to resolve the country’s problems in any real sense (the majority of incoming money ends up in the hands of the local elites). More critically, it short-sightedly reduces the relationship between Lebanon and its diaspora to a flimsy transaction premised on sentimentality and consumerism: the quiet village life and the loud alcohol fueled nightclub. Instead of a meaningful relationship wherein the diaspora contributes positively and effectively to the creation of a new Lebanon, the end of the summer has left the country with larger piles of garbage, more poverty, a deepening sense of alienation, and worsening crises.

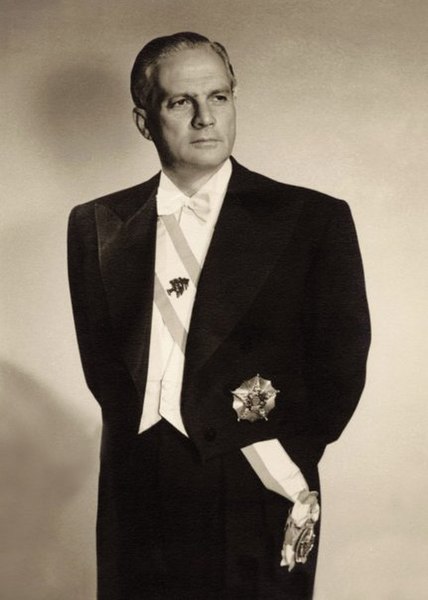

This is not the first time that the return of Lebanese immigrants to Lebanon has been greatly encouraged as a balm for deep seated problems. Nor, sadly, was 2022 the first time that such a promise failed to deliver any real change or relief for the Lebanese people. In 1955 the president of Lebanon, Camille Chamoun, declared the summer of that year the “Summer of Emigrants,” and invited all Lebanese “living abroad” to return “home.” The backdrop to this announcement are the efforts by some political parties to (re)engage the Lebanese in the diaspora with Lebanon’s culture, society and politics. For these primarily Christian-majority parties like the Kata’ib, this re-engagement held political and economic benefits. For example, in 1945 the Kata’ib held its first Emigrants Conference to push the post-independence government of Lebanon to “erase the vast distances between resident Lebanon and faraway Lebanon.” Adding to these efforts was the work of some newspapers in Lebanon which promoted the pressing need to maintain an intimate link between the mahjar (land of emigration) and Lebanon in an ongoing campaign of editorials. Most notable of those is al-Ra’id, a Tripoli based newspaper whose editor, Jabr Jawhar, was an indefatigable crusader for connecting immigrants with Lebanon. Jawhar himself had traveled to Brazil and Argentina multiple times between 1947 and 1953, each time reporting extensively and enthusiastically about his visit to the readers of the newspaper. After his last visit to Brazil, he wrote a letter to the Lebanese president Camille Chamoun asking him to initiate a series of steps by the government to encourage immigrants to return “home.” Similarly, some immigrant organizations in North and South America were equally keen on strengthening links between themselves and their children, on one hand, and Lebanon on the other. For example, in February 1954 the Southern Federation of Syrian Lebanese American Clubs reminded the assembly of its decision to hold the 1955 overseas convention in Syria and Lebanon, “and that an estimated 1000 persons are expected to be present.”

The culmination of these diverse efforts, across more than a decade, was the “Summer of Emigrants”: a three months’ window to more firmly link Lebanon to its diaspora. The Lebanese government set about making the summer an unforgettable series of events. The ministry of tourism spent nearly 1.3 million Lebanese lira (nearly 1% of the annual budget) to cover the costs of these events. The majority of this investment went to pay for overwhelmingly European theater and dance troupes, for two performances by the musical troupes of Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum and Syro-Egyptian Farid al-Atrash, to attract the world championship of water skiing to Lebanon, for hosting festivals and parties across Lebanon, and for a publicity campaign across the diaspora. Towns and municipalities held their own mini festivals as well to celebrate the return of the “immigrant sons.” For instance, the municipality of ‘Alay held a series of events to celebrate the “Week of Emigrants.” The opening event was a parade of decorated cars “representing historical scenes from the heart of Lebanon’s history. A Phoenician ship…, the columns of Baalbek, and seven horsemen riding Arab horses each representing an Arab country.”

In anticipation of the arrival of thousands of returning emigrants, the Lebanese government commissioned a commemorative book titled Lebanon: Country of Tourism and Summer Vacations. The book was in fact a special issue published by The Salvation Message magazine, in collaboration with the Ministry of Tourism. The book itself–like other publications from that period–was really a narration of Lebanon as a nation. In its 150 pages it sought to introduce emigrants to two Lebanons: one that is a modern urban society that has preserved its village values and traditions, formed from time immemorial by the “Gods.” The other was a very modern Lebanon that is “Western” in its consumerism and services. (A precursor to this past summer’s social media campaigns). Thus, across its pages Lebanon displayed the multiple contradictions of a country and its people trying to become a nation; contradictions that were hardly resolved by the returning immigrants, and that were the subject of much debate in the summer of 1955.

In one newspaper account after another, writers criticized the project for its many perceived failures. A commentator in al-Anba’ newspaper wrote in September 1955 that all the extravagant expenditures, which he listed in detail, were “wasted” on visitors from Egypt, Syria and Kuwait, and the elites of Beirut, whilst very few immigrants in reality attended the concerts, plays and festivals. (Al-Anba’, September 9, 1955, p. 6) Financially, he added, the summer season of the Year of the Immigrant was “the worst season the country has seen in many years.” Another complaint, this time from an immigrant, appeared under the ironic title of “One Family!” In his letter to al-’Amal newspaper (which printed it on the front page), Najib Sa’ab complained about the race-tinged double-standard employed by the Lebanese government in welcoming returning immigrants during the summer of 1955. He wrote: “I do not understand the logic behind the government’s great interest in our…immigrants returning from the American lands, while ignoring immigrants from the African lands?” (Al-’Amal, August 6, 1955, p. 1) A resident of Lebanon reported another line of complaints by immigrants spending the summer of 1955 in Lebanon. He reported that many complained to him about being exploited by Lebanese residents who inflated the prices for immigrants by tenfold and more. Running counter to the narrative of the loved ones returning home, he wrote: “Our brothers find it strange that everything here has a price, and a high price…a smile has a price, just like any emotion displayed by residents here towards them [immigrants] costs money.” (Al-Ra’id, August 20, 1955, pp.1 & 3) Finally, another writer criticized the overemphasis on “Western” cultural events in the Summer of 1955 to the exclusion of Lebanese artists, performers and singers.

But the most damning criticism came from Kamel ‘Abdallah, a journalist writing in al-Anba’. In the August 12, 1955 issue of the newspaper, and under the column “Pen and Shovel,” he wrote a scathing critique of the government’s “Summer of Emigrants,” as a failed effort to replace real economic progress and planning with a poor excuse for policy and programs. He wrote:

The government tries sometimes to carry out some activities to show its vitality…even though the evidence of such vitality are few and rare…[amongst these initiatives] is the Summer of Emigrants. So, we succeeded in attracting some of our brothers who fled this country as immigrants. That is beautiful and laudable. But how did we prepare for this [Summer of Immigrants]? We assumed that the immigrants were uneducated and uncivilized. We presumed them to be sentimental, and wanted to impress them with [only] appearances, so we threw them parties, and a week-long welcome filled with sentiment, crying and myths about the past…and that was it…and you government officials were satisfied with that. But in reality they faced incidents of crime, murder, poverty and the shallow facade of the ruling party…All we care about is that some profiteers will gain some money from our immigrants, but how did the country and government benefit in terms of gaining the confidence of immigrants and their contributions in elevating the standard of living in Lebanon? (Al-Anba’, August 12, 1995, p. 5.)

This and other broadsides inexorably lead one to conclude that while a great deal of hope was placed upon the 1955 Summer of Emigrants, in the end it was limited in its ability to attract immigrants, and even less so in convincing them to invest in large enough ways in Lebanon. Data from later years bear out this conclusion when Lebanese immigrant investment dropped below the levels of the years before 1955. In part this was due to the political crisis that gripped Lebanon and exploded into an outbreak of internecine violence in 1958. But, this hardly dissuaded government officials, political parties, and newspaper editors from continuing their efforts in subsequent years to engage immigrants, and appeal to them for financial support. The pattern for the engagement with the Lebanese diaspora remained the same throughout those years: using sentimentality to attract immigrants, and seeking money from them for real and fictitious projects. Missing from this formulation across the last 70 years are any real and sustained efforts to engage immigrants for their ideas, skills, and abilities to contribute to the social and cultural transformation of Lebanon into a stronger democracy that is committed to social justice and equal opportunities for all. This summer constitutes another missed opportunity.

- Categories: