Ameen Rihani and Zoe Norris: Cross-Cultural Friendship of Writers at the Ragged Edge

Independent scholar Eve M. Kahn, former Antiques Columnist at The New York Times, writes about art, architecture, and design for the Times among other publications. She is biographer of artist Mary Rogers Williams (1857-1907) and writer Zoe Anderson Norris (1860-1914).

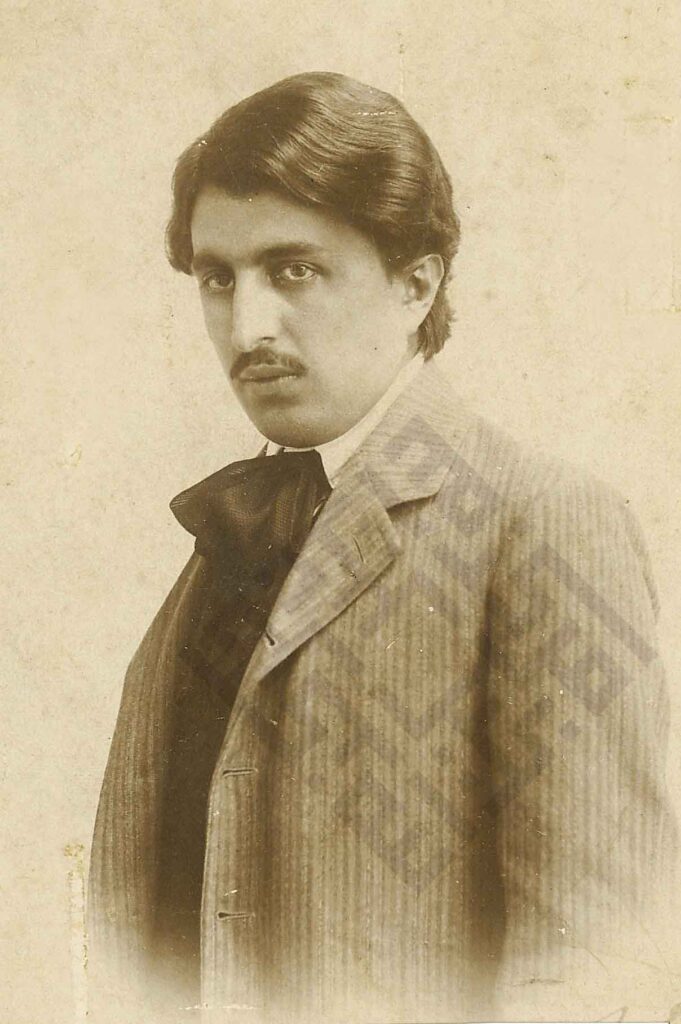

In the early 1900s, two self-invented writers in New York, Kentucky-born Zoe Anderson Norris (1860-1914) and Lebanon native Ameen Rihani (1876-1940), forged an improbable but enduring friendship. Their kindred-spiritedness is evident in newly identified archival material at NC State’s Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies.

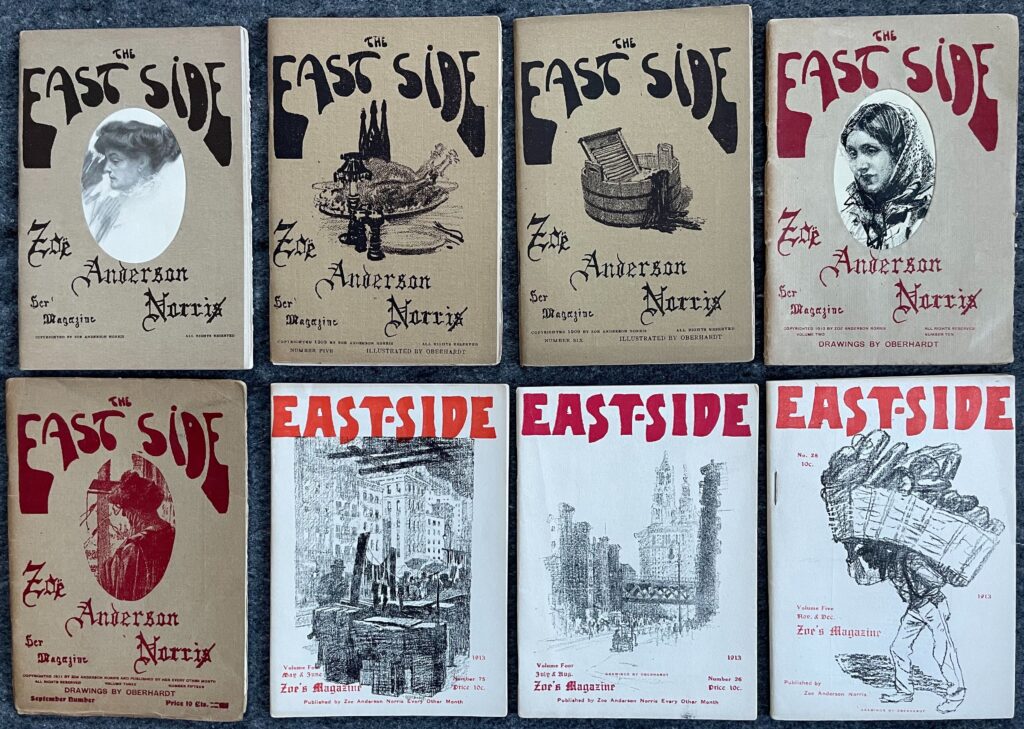

I’m an independent scholar, finishing a biography of Zoe (as everyone called her) for Fordham University Press, and the exhibition that I have curated about Zoe runs through May 13 at the Grolier Club in Manhattan. She prolifically authored fiction and journalism for publications including her own soul-baring bimonthly magazine, The East Side (1909-1914). She focused on the sufferings of immigrants living near her apartment on the Lower East Side and pleaded for government and charity efforts to help the poor. (The issues from 1909 to 1913 are digitized here and the rest are here.) She attracted people to her cause with vivacity and sociability; every Wednesday or Thursday, she hosted restaurant dinners for her intentionally disorganized nomadic organization, the Ragged Edge Klub. Known as a Queen of Bohemia, she imposed no dues, no bureaucracy on her Ragged Edgers—most of whom, like her, were creative yet falling into poverty. Instead, she promised “No Gavel, no Scolding, no Calling Down. Only the Killing of Kare,” as she wrote in The East Side.

A few months ago, while scouring the internet for more of Zoe’s biographical traces, I typed “Ragged Edgers” into my browser. I was astonished to find NC State’s digitized typescript for a speech that Rihani gave at one of her dinners, around 1910. I knew that a few of her writings mention him admiringly, and that she had explored his New York haunts. But I had not realized that she remained close enough to him to invite him to speak at her Klub, nor that he admired her in return.

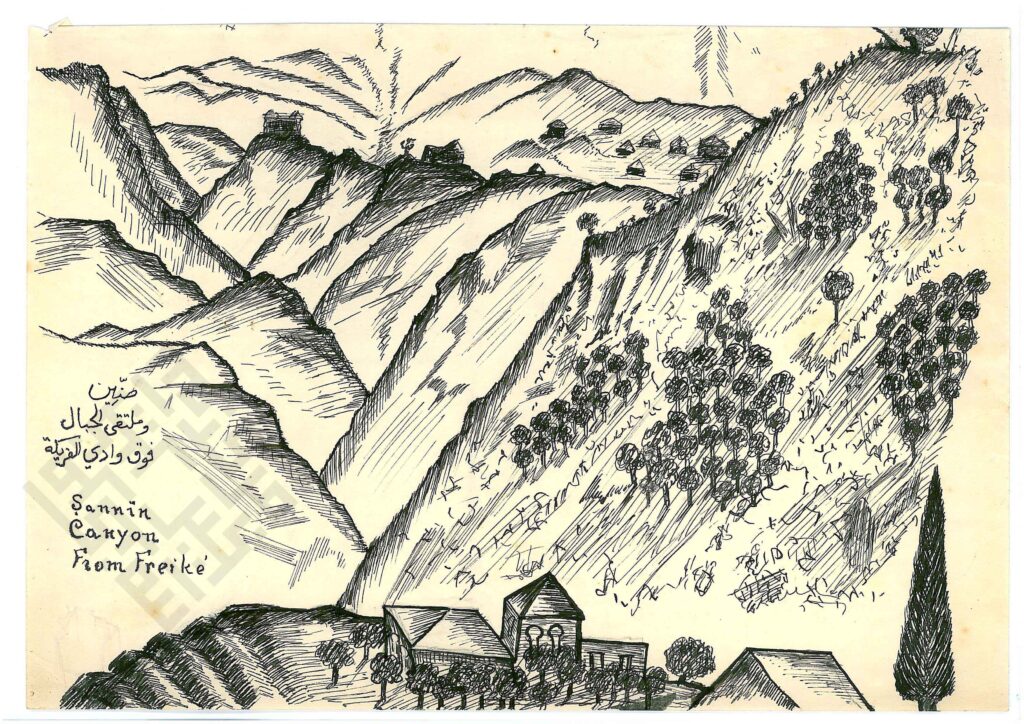

Zoe and Rihani likely met in 1901, soon after she moved to New York and began contributing to periodicals as prominent as Frank Leslie’s Monthly while befriending other culturati. She had grown up relatively impoverished in Harrodsburg, Kentucky—“a little old dog kennel town,” she called it in The East Side. She was the 13th of 15 children of an evangelical pastor, Henry Tompkins Anderson (1812-1872), who devoted much of his time to unprofitably translating the New Testament from ancient Greek sources. She became a dedicated New Yorker after escaping from a bad two-decade marriage to a Kansas storekeeper, and she had long abandoned her father’s rigid Protestant dogma (although she remained a devout Christian). Rihani, the eldest of six children of a dry-goods merchant, a Maronite family emigrated from Freike to Brooklyn, may have sympathized with Zoe’s memories of a constricting, conservative childhood and a large brood of siblings.

Zoe and Rihani joined the Pleiades Club, a nomadic group of intellectuals whose speakers over the years included Mark Twain. Rihani’s digitized papers document his and Zoe’s mutual friends in the Pleiades orbit, such as the Irish-born writer and editor Michael Monahan, who published Rihani’s work in his sporadic magazines The Papyrus and The Phoenix and commiserated with Zoe as she struggled to keep The East Side afloat.

Zoe, like Rihani, suffered career setbacks due to controversial writings. In 1902, Funk & Wagnalls published her first novel, The Color of His Soul, about a hypocritical Socialist orator named Cecil Mallon, living in Harlem and preaching sympathy for the Lower East Side’s “wage slaves.” But he impregnates and abandons his working-class teenage mistress, and the book’s heroine-narrator, a Southern-born freelance writer named Dolly (Zoe’s avatar of course), exposes his villainy. Days after the book debuted to rave reviews, one of Zoe’s neighbors in Harlem, a hard-drinking Socialist orator named Courtenay Lemon, threatened lawsuits, and the publisher withdrew it from the market. The scandal scared away some of her magazine employers, and Zoe scrambled to find new freelance outlets. In 1903, Rihani’s musings on religious tolerance and critique of the clerical class, The Triple Alliance in the Animal Kingdom, caused him to be excommunicated by the Maronite church. He returned to his native Lebanon, and his absence made appearances in Zoe’s fiction and journalism.

In “The Smoke of the Nargileh,” one of her circa-1905 unpublished short stories (descendants own the typescript), a newspaperwoman describes an evening’s adventure in Little Syria, a Middle Eastern neighborhood on Manhattan’s Lower West Side. (It was largely erased in the 1960s to make room for the World Trade Center.) The narrator dines at a restaurant with two male colleagues and a widowed Syrian immigrant named Mrs. Kohler, whose late husband had been a newspaperman. Mrs. Kohler had first met the narrator during “our farewell visit to the Syrian poet who was going home to Lebanon”—that is, Rihani. (It is not clear if any of the story’s other characters are based on real people, although Zoe had a habit of “making copy out of her friends,” as Monahan put it.) The restaurant is thronged with immigrant newspapermen, smoking hookahs and “scribbling at copy of some sort … taking notes for to-morrow’s edition.” Mrs. Kohler, whose husband had frequented the restaurant, worries that her outing with strangers will make the papers: “You have no idea how these people watch and talk. Women have to be very discreet in Syrian society,” she warns her companions. The story ends with the widow explaining that Syrian women smoke—“They think nothing of it”—so the narrator resolves to try a nargileh: “I’ll take a puff at one if it kills me.”

In 1905, Zoe reported for the New York Press on shopping in Little Syria with an artist friend. She was tempted to splurge on her own nargileh, although the device, at $25, would cost nearly as much as her month’s rent. Hoping futilely for a price break, she tells a storekeeper about her friendship with Rihani: “He was not only a good translator, but he was very handsome. Beautiful eyes! He used to weep over the prices they paid him for his verse here in New York, though. Nearly ruined his eyes. He said they used to give the old Persian poets droves of camels for a quatrain. Here he got two dollars.” She had tried to console him by observing that “he wouldn’t know what to do with a drove of camels in New York unless he started a circus.” Rihani’s decision to exchange “a stuffy flat in Brooklyn” for his picturesque native land, “to sit under his own vine and fig tree,” made sense to Zoe. The storekeeper added that Rihani, given his “advanced ideas in regard to religion,” was safer in the Middle East than in Little Syria: “They were about to burn him at the stake.” Zoe and the artist end up quoting Omar Khayyam’s paeans to wine while trying to order red wine or cocktails in the neighborhood’s Muslim-owned restaurants. In the absence of alcohol, Zoe paraphrased Khayyam: “I turn down the glass … because it seems impossible to get it filled.”

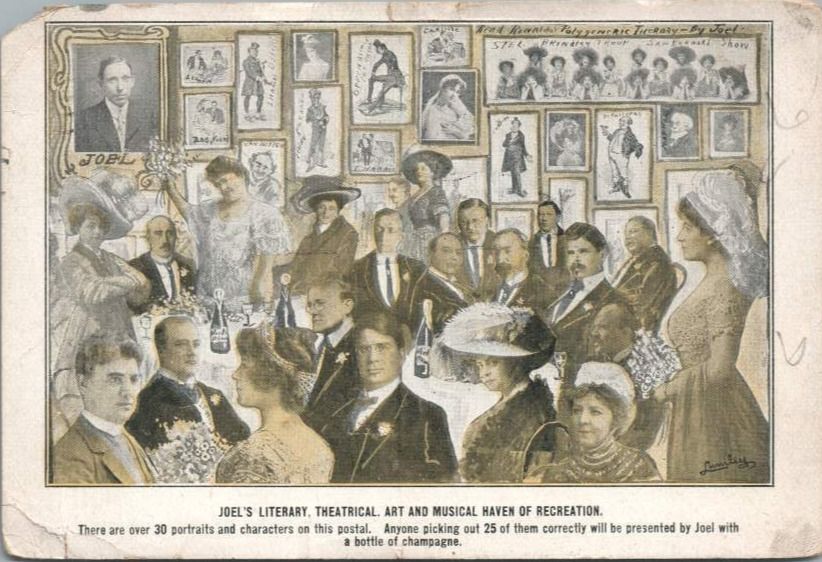

In 1910, soon after Rihani returned to New York, he gave a dinner speech to “My dear Ragged Edgers” at a restaurant—their favorites included Joel’s Bohemia near Times Square, known for its late-night servings of chili con carne and blueish cocktails. The party’s “Humble Hostess” (as Zoe called herself) would agree with his presentation, Rihani explained. Western bohemians like the Klub members were feigning poverty in a crassly materialistic society, while Lebanon’s poverty had an authentic quality: “in my Country everything, except our sky, and our manners, is decidedly ragged edge; I do not mean unappealing, unattractive,- no. I would be casting a slur upon this Club .. But surely a ragged edge is better than no edge at all, especially when it is a case of studied raggedness. Ah, I’m on to you,–I got your number. Slang this? Yes; but never mind where I got it. … our Edgings are woven by the Poets and Prophets, and tinged and scented by Time, while yours are woven by Machinery and made ragged by the two-by-two rule.” His homeland straddled the border of Orient and Occident, “geographically, historically, spiritually. We are the warp and woof, as it were, which connects the Silk of India with the Muslin of Manchester.” He called his people “non-racial … super-racial … a wonderful spiritual Nothing.” Europeans and Americans, by contrast, amounted to “an outrageous unsatisfying material Something. My people come to your Country for money, you go to ours for inspiration, for spiritual solace, for an indefinable something.”

Those travel souvenirs may be illusions, Rihani said, but they nonetheless surpassed “neatly canned and cleverly advertised humbugs. Oh Gullibility, thou sister of and wife of Mammon, what a power is thine. … But I must not digress too much. I shall keep to the Edge to-night and though it be ragged. … in my Country almost everything is crude, natural, poetic, inspiring. We know not the comfort which only the rich among you enjoy, nor the squalid poverty which huddles and groans in your slums. Our rich are ragged edge, and so, too, our poor. But the garment they all wear is of solid and reliable material. … trimmed high-lackered Ugliness, both in fashion and manner, is being imported into Syria from across the Mediterranean and the Atlantic.” This so-called form of “Civilization,” he said, was “rather the residue of Civilization … The European merchant and the American Missionary come to us with their big scissors and try to cut off the ragged edgings of our Garment. Another raggedness of an old garment, like the deposits in a jar of wine, are a proof of its quality. That is why the Merchant & the Missionary get no thanks for their labor. Moreover, they try to weave on the Majesty of Antiquity, not the fine solid material, but the shoddy, of Modernity. And after all, what is civilization but luxury flounced with toadyism, and comfort ruffled with fake?” He closed his talk with a “ragged edge truth”: his listeners only differed from his countrymen by being “better clothed, better lodged, better fed, and better faked.”

Zoe quoted Rihani in her last published writing, the January/February 1914 East Side issue, which she mailed out a few days before her death (due to heart failure) on February 13, 1914. The magazine opened with descriptions of her recent dream that she would die soon, and her preparations for heading to “the Undiscovered Country.” She hoped that her good deeds would result in a pleasant afterlife, that she had “interested anybody in the poor for their benefit.” She remembered Rihani’s description of Jews in Tiberias, living in “ghastly” poverty, yet maintaining perfect faith in God. Her Lebanese anti-sectarian friend, in telling her about Middle Easterners different from him, had made this Kentucky-born Protestant turned skeptical Manhattanite wish that she could metamorphose one more time: “How beautiful that must be; to have a perfect faith in God!”

And how fortunate I am, to have stumbled upon NC State’s digitized typescript, enabling me to give readers such a vivid sense of how Zoe’s friends tried to enlighten each other.

- Categories: