Fighting Injustice: The Story of Herbert Nassour

Watch the documentary, Herb Nassour: The People’s Doctor, in English with Spanish or Arabic Subtitles.

Far too often, the complex history of Lebanese immigration is collapsed into a few “success” stories, measured by accumulation of fame and fortune. Such tales are certainly real and admirable, but fall short of telling the whole story of immigration. They warp our expectations of what makes for success by projecting the false impression that accumulation of money and celebrity was/is the only reality of immigrant life and work, and that it is the only thing worthy of recognition. Such simplistic narratives ignore the rich and varied experiences that define Lebanese immigration. Among the most glaring elisions are of those individuals who shunned the pursuit of money, and in its place sought after social justice and equality for their immigrant community and society as a whole. Lebanese diasporic community organizers, avant garde intellectuals, and activists were instrumental in these alternative pursuits, in transforming their host societies for the better, and envisioning a more progressive and equitable Lebanon. Yet, they rarely are celebrated in news reports, or on award stages.

One of these unheralded crusaders is Dr. Herbert Nassour, Jr., who dedicated his life to bringing affordable healthcare to the poor, the homeless, the sharecroppers and poor farmers, and to the downtrodden in Texas.

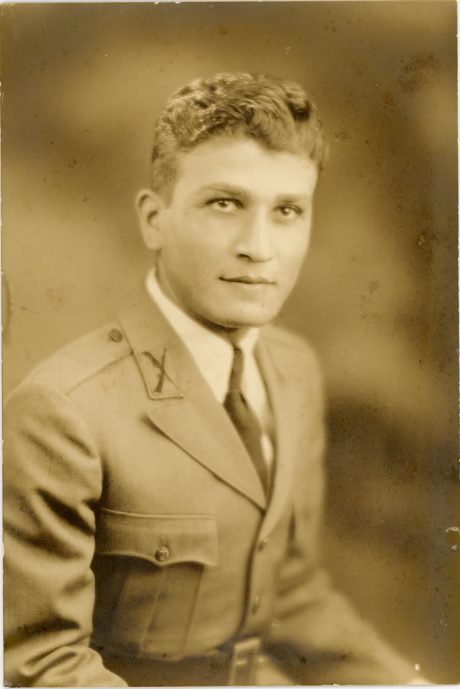

Herbert Nassour, Jr. was larger than life. It is not simply that he was—as his wife Hoda described her first impression of him at the port of Beirut in 1937—an imposing “tall Texan [football player] with broad shoulders,” whose parents had immigrated from the villages of Khirbeh and Haqel, in Lebanon. Nor is it that he grew up in a racially divided Texas, where he fought for every opportunity from schooling to work, because he and his friends were deemed less than white. His attempt to bring rural healthcare to the villages of Mount and South Lebanon, his service in WWII in the US Army and encounters with King Abdallah of Saudi Arabia are also just glimpses of his remarkable legacy. Even his crusade to bring affordable healthcare to Texans does not tell the whole story of this giant of a man.

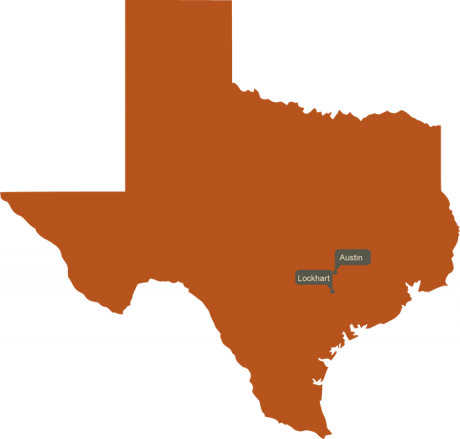

Rather, Hebert Nassour looms large even today because of the sum of these various parts, which speak of a tireless, dogged, lifelong and selfless pursuit to serve others. His calling was partly an inheritance from a pioneering grandfather and an activist mother. In other parts, it was shaped and crystallized by his own encounters with race, poverty and power from the streets of Lockhart, Texas (where he was born and raised), through the halls of universities, and into the farming fields of Lebanon and Texas.

Herbert, Jr. was born in 1917 to Mary Moses and Herbert Nassour, Sr. From his mother he learned, among other things, to speak out against injustices. It was she who first refused to accept the racially divided world of Lockhart, and who fought “to change all that.” Mary grew up knowing the impact of discrimination. In 1901, when she was seven and dressed in a new dress and shoes that “Papa bought in San Antonio,” Mary went for her first day at elementary school in Lockhart only to be turned away and told that she could not sit and learn with white children, but must attend the school for “Mexicans.” She later recalled, “the Mexican school wasn’t really a school at all,” but a mud-filled room with a teacher “who was always drunk.” Referred to later in life as “La Madre de los Mexicanos,” by local Latino sharecroppers, Mary parlayed this and other personal experiences with bigotry into a life of helping and interceding on the behalf of the sharecroppers, many of whom did not speak English. Appearing in court or at the cotton ginner and speaking on their behalf, or translating for them at the doctor’s office became a regular part of her daily life and activism. When Father Shanahan would interrupt mass and order all Hispanic congregants to leave, for fear of offending the wealthy whites in church, Mary scolded him and told him how un-Christian he was. In this manner, Hebert, Jr. grew up learning from her the importance of fighting for human dignity.

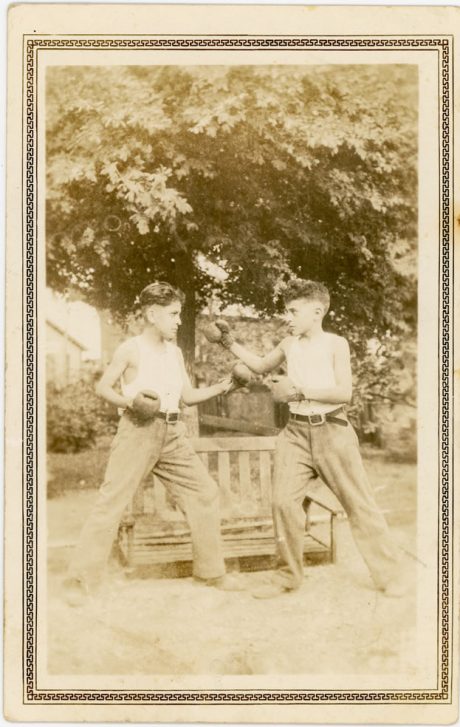

From his maternal grandfather, Nasrallah Moses, he learned how to fight in a different way. An early lesson came on his first day of elementary school in Lockhart, when he was chased by a group of white boys throwing rocks and racial epithets—“Dirty Dago!”—at him. Visibly upset, he ran to the safety of his grandfather’s store. When Nasrallah learned what happened, he told Herb: “Don’t run away…You got to fight ‘til you can’t fight no more.” With what would become a lifelong mantra, Herb went outside to face his tormentors and stare down a white supremacy predicated on fear and violence. Nasrallah soon separated the boys, gave each one a candy stick and walked them to their homes where he told their parents: “You got to teach your boys to get along with other people before it’s too late.”

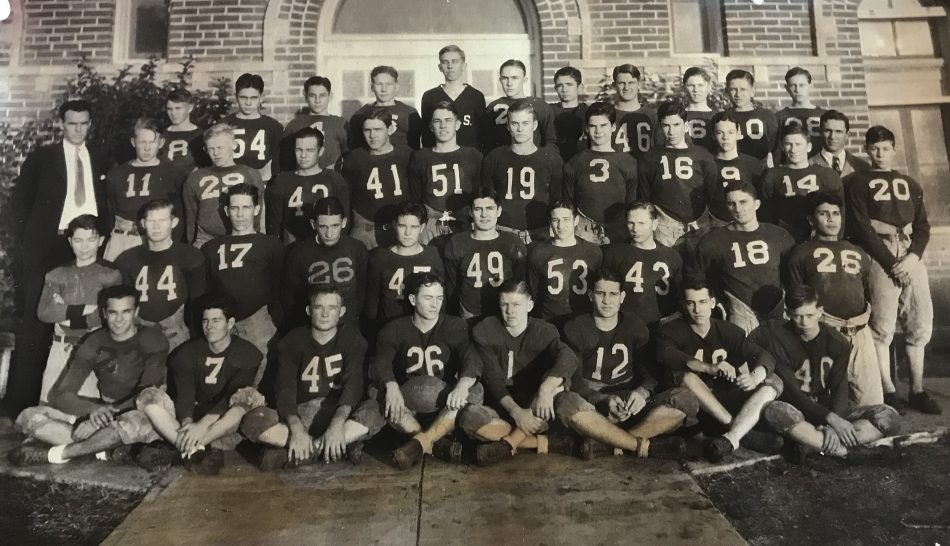

Herb channeled his anger at subsequent injustices into similar headstrong confrontations and refused to back down. It was his “aggressiveness” on the football field that allowed him to enter the “whites only” Lockhart High School. It was the same attitude that he displayed in restaurants or drugstores where waiters would refuse to serve him or his friends until they sat in the backroom with African Americans and Latinos. He would throw plates at them, or break the malted milk glass and refuse to budge from his spot.

But some things he could not change, certainly not as a teenager. One incident in particular left an indelible impression on him, and firmed his decision to become a doctor. Among the customers of his parents’ store in Lockhart, was a young Hispanic sharecropper named Tony Garcia. Tony brought his wife, who was in her second day of a very difficult labor, into town to find a doctor with the help of Herb. As they went from one doctor to the next pleading for help, the only response they received was a demand for money upfront before treatment. Without the means to pay in advance, all Herb and Tony could do was transport her to Nassour’s home where Mary tried to save both mother and child. By that time, it was too late and both passed away.

In the face of this unnecessary and cruel tragedy, Herb became resolute in his decision to become a doctor who would care for the poor and neglected. But his path to this goal was, once more, blocked by racial barriers in Texas. After finishing his undergraduate studies at the University of Texas in 1936 with high grades, he was turned down by the two Texas medical schools, Baylor in Dallas and John Sealy in Galveston, because they would not accept non-whites. His boiling frustration with an unjust system finally forced Herbert to leave the United States—at the recommendations of a Jewish doctor at John Sealy—and go back to Lebanon where he enrolled in the medical school of the American University of Beirut.

In Lebanon, Herbert not only excelled in medical school, but he was also finally not a “minority.” His days at AUB among other Arab medical students, eating foods familiar to him from his childhood, and surrounded by his large extended family, all gave him a sense of belonging that he could ease into rather than have to fight for every step of the way. Yet, challenges remained albeit in the form of abject poverty and lack of medical care that he witnessed in his parents’ natal villages. On his trips to Khirbeh, Haqel and other rural parts of Lebanon he found outbreaks of typhoid, malaria and dysentery, as well as parasitic diseases that were as rampant as they were easy to contain. Life expectancy for men was around forty years and lower for women, and infant mortality was high. Solutions were relatively easy: inoculation against diseases like typhoid, deep-pit latrines to improve hygiene, and providing supplies of medicine and healthcare providers. But resources were another matter in a city where the bourgeoisie either did not know of, or did not want to see, the desperate conditions that prevailed a few miles outside Beirut, or in the city’s poorer quarters. Undaunted, by the time he left Lebanon shortly after WWII—with his wife Hoda whom he met and married in Lebanon, and their three children—he had worked with other AUB medical students and professors to establish seven rural healthcare clinics.

With this same zeal he returned to Texas to finish his residency and begin a life-long career of securing healthcare for those deprived of it by structures and attitudes of social and economic prejudices and racism. In Hamilton, Garland and then finally Austin, Herbert and Hoda Nassour built community hospitals that sought to bring affordable care to the poor and needy. But his efforts at introducing universal healthcare (standard small fees for procedures, distributing cost among larger annual subscribers, and providing free care for those who could not afford it) throughout his 40 years of practice in Texas he met with unyielding resistance, and unscrupulous tactics, by local doctors, the Texas Medical Association, and the growing health insurance business.

Their efforts were successful, as measured by how many times they forced Dr. Nassour to close his operation (at least three) and face disciplinary action on trumped up charges (four or five). Nonetheless, despite these disruptions, Herbert succeeded spectacularly and in immeasurable ways when we look at the number of people he treated and helped, and at the immense pressure he created on other physicians and hospitals to follow his lead or explain why—as individuals and institutions dedicated to help people—they refused to provide care. So, while Dr. Nassour started his career with the tragedy of being unable to help Tony Garcia’s wife in Lockhart, he was able to save the life of Hernanda Martinez in Austin even after she was turned away from every hospital in town because she could not pay.

These two incidents bookend a career of a Lebanese-American who—like his fellow physician in Oklahoma, Dr. Michael Shadid—neither amassed fortune nor accolades. What money he had he gave away or put into community hospitals. He and Hoda opened their homes to countless people in need, and he shepherded the careers of many future doctors including his own daughter-in-law. Throughout his career, he bypassed rules and borders in order to achieve his goal of providing comfort and quality medical care to those in need regardless of who they were.

- Categories: