Anthony Mansoor: An Unlikely Profile of a Lebanese living in Mississippi

On January 6, The Atlantic featured an article “How White Flight Ravaged the Mississippi Delta.” Focused on the town of Tchula located about 70 miles north of Jackson, the town is “currently listed as the fifth-poorest town in the nation with a population of more than 1,000.” Focused on unsurprising economic struggle of a small farming town, this article’s narrative weaves the history of the town through the New Deal, World War II, the Civil Rights Movement, and the current controversial mayorship. Sitting along racial and class lines, Tchula’s story includes the relationship of African-Americans and white residents. But, Tchula is also home to Anthony Mansoor, a Honduran born Lebanese-American hardware store owner who arrived in Mississippi as an exchange student in the 1950s. His story–especially Mansoor’s experiences as Lebanese in the Jim Crow era and as a business owner in town, offers a unique conversation about racial and ethnic identity in the American South.

When Mansoor arrived in Tchula in the 1950s, his eyed were opened to the consequences of African-American involvement in voter registration drives. Some were fired or denied credit at banks. Opponents of racial integration and empowerment targeted advocates of the movement, political figures, and town business owners. Around 1967, Mansoor’s hardware store became a target of violence between the Klu Klux Klan (KKK) and an African-American activist. As Mansoor recalled,

Other Klansmen followed and began turning over counters and racks, “just demolishing the store,” says Mansoor, who remembers telling his pregnant wife to run home. “I called the sheriff—his name was Andrew Smith—and he said, ‘There’s nothing I can do about it.’”

After the incident, Mansoor lost a legal battle against the KKK members who demolished his store, which led to a boycott that persisted for decades. Years later, when Mansoor suspected arson after his store caught fire, he considered fleeing Tchula, but decided that he would not “let them drive me away.” It wasn’t until an increase in drug use in the 1980s that created such an unsafe environment for Mansoor and his family that they moved to a suburb of Jackson. Commuting to and from Tchula each day, Mansoor’s business is still standing, if not entirely thriving. In the most gracious act of all, Mansoor remained in touch with the mother of the KKK member responsible for destroying his store and, arguably, stifling this livelihood. When she died, she bequeathed him some of her belongings in a final act of peace.

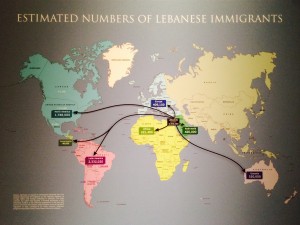

Anthony Mansoor’s story is one of unique circumstances, but not entirely uncommon in the Lebanese diaspora. We know that there are about 1.3M Lebanese in the United States (1.7M in North America), which is the largest diasporic population in the world. Those states with the highest concentration of Lebanese-Americans include Michigan (11%), California (9%), Florida (6%), Ohio (6%), and Massachusetts (5%). Through the work of the Khayrallah Center, we know even more about the Lebanese population in North Carolina and the deep south. Mansoor reminds us that the tradition of Lebanese descended immigrants, business owners, and humanitarians can be found anywhere.

If you’re interested in reading more about Lebanese-Americans in the Jim Crow South especially as it relates to racial identity, please check out the Center’s November 2013 newsletter article, “How the Lebanese Became White?” (pages 7-9).

- Categories: