Counting the Lebanese in the US: 1900-1930

This post is co-written by Marjorie Stevens and Peter Knepper. Marjorie is Senior Researcher for the Khayrallah Center with a primary focus on archival research and development. Peter Knepper is a PhD student in Sociology at NC State. He joined the Khayrallah Center in the Summer of 2015 to prepare preliminary analyses and create visual representations of census data to help inform the public of historical patterns of Lebanese immigrants.

How many immigrants were living in the United States between 1900 and 1930? Where did they live? How many of them were women? How many were married, single or divorced? How many children did they have if any? What was their average age? Until now, researchers did not have reliable answers for these demographic and social questions about Lebanese immigrants in the United States. Most information compiled by researchers was based on rough estimates that, more often than not, provided wildly divergent numbers leaving one more perplexed than informed. Recognizing this pressing need, the Khayrallah Center launched a project last spring to provide reliable population data for first-wave Lebanese-Americans from 1900 to 1940. The Center mined decennial US Census data from 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930 and 1940 to create a comprehensive profile of the earliest Lebanese-Americans and to share this information with the public. This fall we will begin releasing our findings in blogs, graphs, tables, interactive maps, a detailed report, and scholarly articles. For this project, we obtained complete US Census files for five decades and extracted individuals born in Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine, and those whose parents were born in those countries. One downfall of this method has been that the 1940 census did not call for individuals to list their parent’s place of birth. Thus, where our data from 1900 to 1930 includes the children of immigrants (or first-generation Americans) our data from 1940 does not, and thus could not be used in this particular blog post which compares populations. Aside from the need to exclude the 1940 census in some instances, the data is somewhat marred with potential undercounting due to the biases of the census takers and other inaccuracies. However, and with these caveats in mind, this data will be the most accurate to date and hence the most useful. What you will note is that this not a linearly growing population adding to its numbers through procreation and continuous immigration. Rather, we find a population that is constantly in flux for many reasons. First, and contrary to the commonly traded narrative about immigration where migrants uniformly travel in one direction to the US, the majority of 19th and early 20th century immigrants to the United States (not just Lebanese), intended to return to their homelands after a few years abroad. They sought jobs in prosperous countries (mainly the industrializing US, Argentina and Brazil) to earn money and improve their family’s situation back home. About one third of Lebanese returned to Lebanon (this is half the return rate of German or North Italian immigrants, but it is double that of Jewish or Greek migrants). In addition, once settled in the United States (or other countries), migrants often returned home for a number of years. Many immigrants, both male and female, left their spouses, children, parents, and extended families behind in their villages and towns. Thus, some returned to Lebanon to escort family to the Mahjar (place of immigration) or to build newer and bigger houses back home and improve the living conditions of their families before resuming their lives in their new country. Some left their families in one part of the US and found their fortunes in others. In other words, the fluctuating data shows that people are leaving and returning, arriving for the first time, marrying and having children, dying and being born. They are expanding their horizons by leaving American cities for work in rural communities, some venturing out on their own, and others moving in small communal groups. Thus, the aggregate number of immigrants fluctuates from one decade to the next in a non-linear fashion. What the numbers show is that the heaviest period of emigration from Lebanon occurred between 1905 and 1914. Immigration ceased with the outbreak of World War I in 1914 and resumed around 1920 but American legislation enacted throughout the 1920s placed quotas that severely limited immigration beyond that time. Therefore, while population growth between 1900, 1910, and 1920 is heavily influenced by immigration, subsequent years’ expansion can be more likely attributed to family growth within the United States.

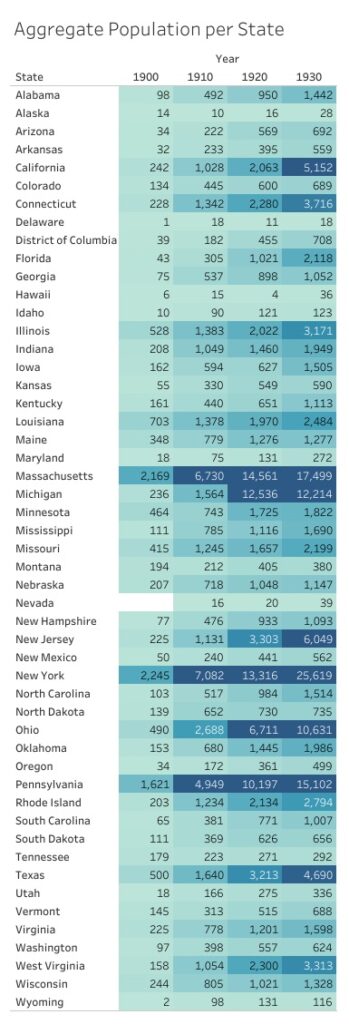

Over the time period of 1900-1930, there are some striking findings in regards to location, and sheer numbers, of Lebanese immigrants in the United States. First, it is clear that the majority of Lebanese immigrants are centralized in the Northeastern region of the country. New York, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Michigan report the greatest number of immigrants throughout the time period. Most importantly, the years of 1920 and 1930. Like many immigrant groups, the Lebanese often settled at first in enclave communities established in large American cities. The Washington Street Syrian Colony in New York is one example. However, these maps and graphs clearly show that neither the northeast nor the Syrian Colony can claim to be the exclusive abodes of early Lebanese-Americans. Regionally, the Midwest has incredibly high numbers of Lebanese consistently accounting for around 25% of the Lebanese immigrant population. In 1920, Michigan had the third largest population by state outranking Pennsylvania. Texas consistently shows high numbers of Lebanese. In 1910 it has the fourth highest number after New York, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts. This may be a result of overflow of immigrants who originally settled in South and Central America but decided to relocate to the United States via the Mexican border. Or it could be due to the fact that those immigrants who were denied entry through the main port of Ellis Island–due to communicable diseases like trachoma, being considered paupers if they had less than $25 in their possession, or for lack of a sponsor American or Lebanese–managed to enter the US more easily through Mexico. Beyond Texas, and in general, this new data shows that the South was demographically more prominent than existing histories of Lebanese migration would lead one to believe. For instance, in 1920, 20% of Lebanese immigrants lived in the South and from 1900 to 1930 that region never accounts for less than 10% of the population. This revelation necessitates a re-telling of the stories of Lebanese immigration to the US, and a shift from an over-emphasis on the northeast region.

Moreover, examining the population by county gives a more precise picture of population distribution. While one Western state may count far less numbers of immigrants than its northeastern counterpart, a particular Western county may still have a significant population that rivals counties in densely populated states. For example, between 1900-1930, Los Animas County, in Colorado, reported hundreds of immigrants living in this remote–and by some measures unlikely–southeastern corner of the state. Aside from showing that Lebanese immigrants were spread throughout the US, this “peculiarity” reinforces our earlier conclusion that we cannot presume that the history and lives of Lebanese immigrants was centered in New England or New York and Pennsylvania. This data begs to cast a wider look and to ask new questions such as what led hundreds of immigrants to a clearly isolated community in the West (servicing mining operations and miners might be the answer in this particular case). At another level, the county map reveals that states with generally industrial economies have more expanded Lebanese settlement. The majority of counties in Massachusetts and counties in Southwestern Pennsylvania surrounding Pittsburgh (Allegheny County) all report high numbers of Lebanese immigrants. This raises another question about the accepted idea that the majority of early immigrants were peddlers and forces us to reconsider the type of work adopted by immigrants and the reductionist idea that they were all successful businessmen who started their careers in peddling. (See the blog post by Linda Jacobs about this “myth.”)

As important as it is to note counties with high populations, we have to give serious consideration to other counties with a single or few immigrants, a phenomenon seen most commonly in 1900 and 1910. (Two such men were Albert Razook and John Mansoor, dry goods peddlers who accounted for the only Lebanese in their respective counties of Sumner and Marion, Kansas in 1900. Razook, age 22 had been in the country 5 years and lived in an American household. John Mansoor, a 42 year old immigrant of 3 years was living with a Russian family despite having his own wife and children elsewhere.) This compels us to consider whether these solitary (or nearly so) immigrants in far-flung countries–many of whom spoke little English–experienced a lonely existence isolated from people familiar with their language and culture. Or perhaps they sought such a life precisely because it took them far away from the densely populated centers in New York or Massachusetts. In short, then, this newly compiled data opens the door for researcher to begin writing a new and more accurate history of the migratory experience of the Lebanese in the US. In subsequent blogs we will continue to highlight aspects of this data and the new questions it poses.

- Categories: