How did migration affect the health of the early Lebanese American community?

This post is co-written by Sarah Soleim, a PhD in Public History at NC State University specializing in twentieth-century United States history, and Marjorie Stevens, Senior Researcher for the Center. For more articles on this topic, check out Counting the Lebanese in the US, our 3-part series on language and identity among immigrants, and our Fact Sheets.

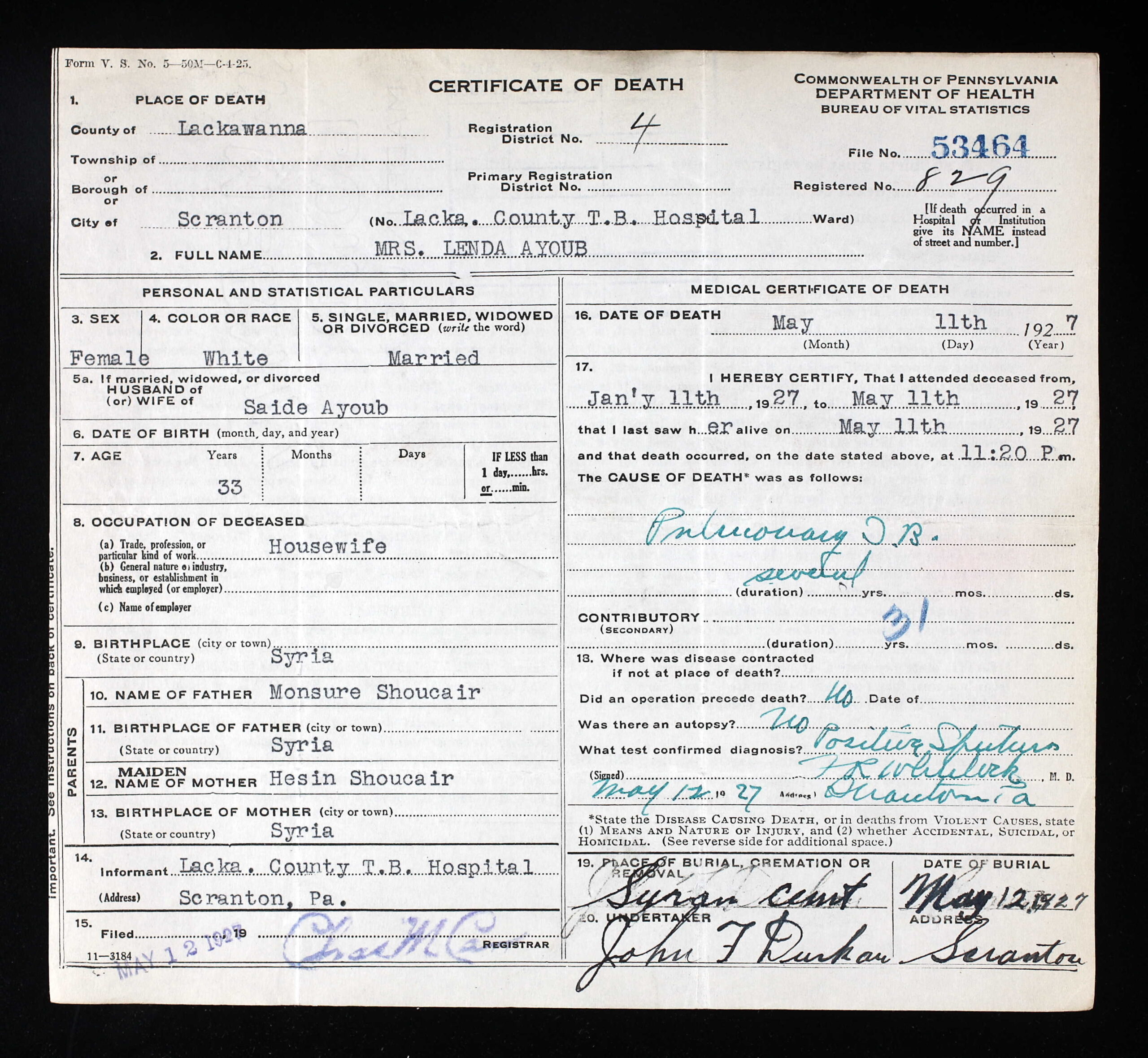

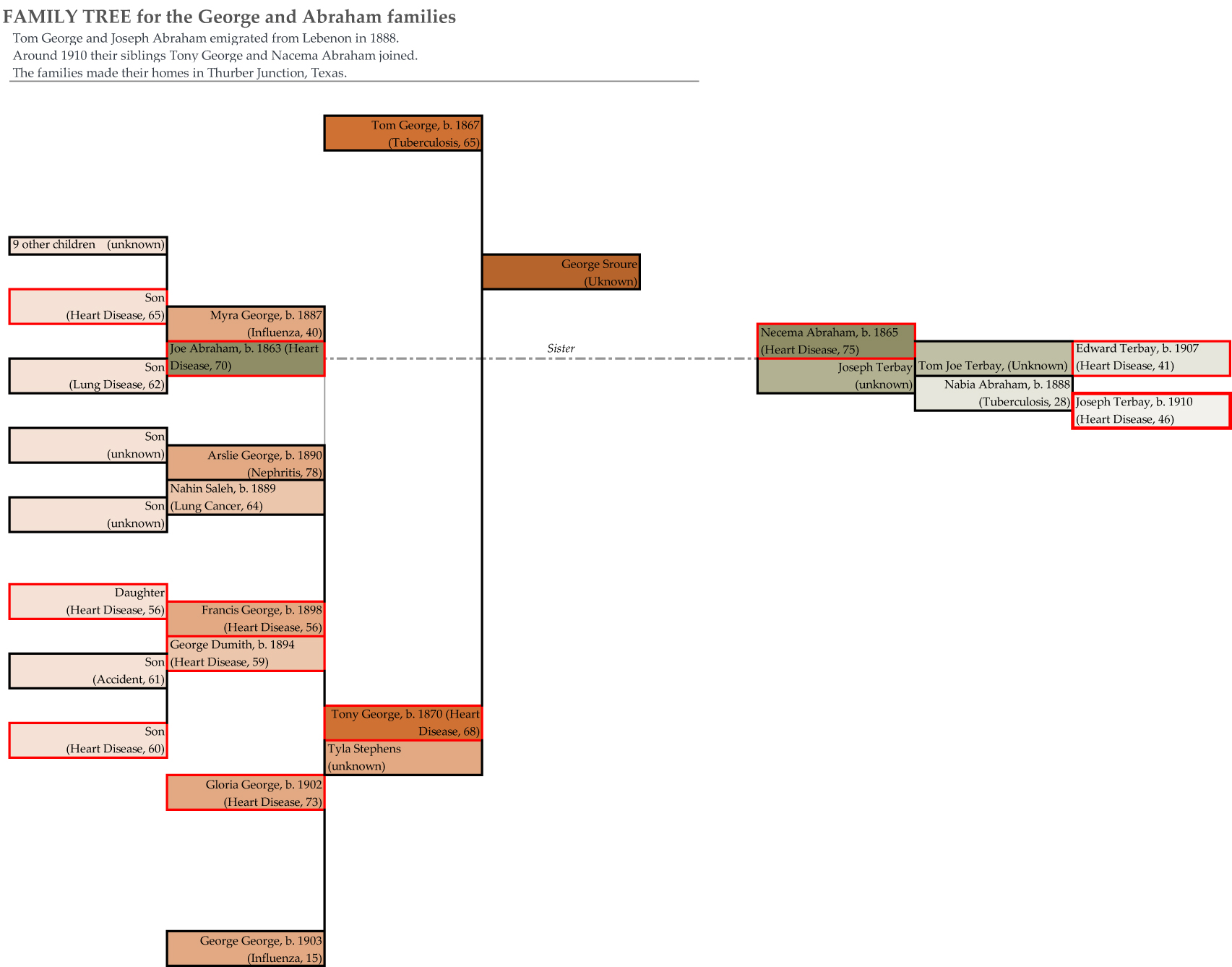

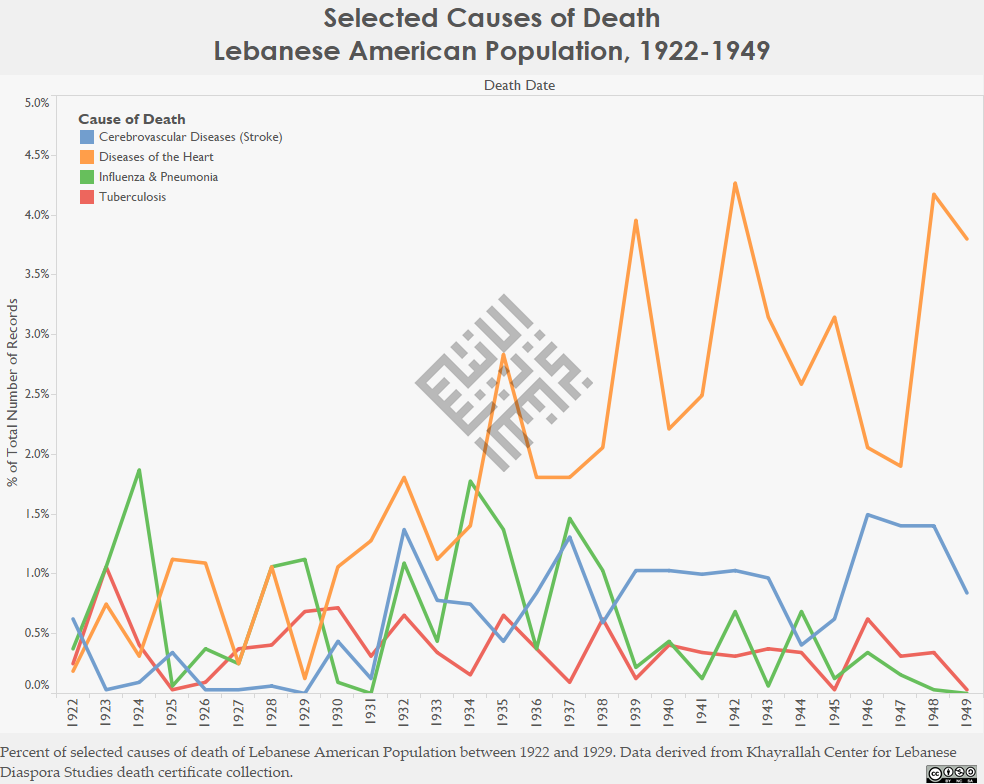

To answer this question researchers at the Khayrallah Center have been studying the impact of migration on the health of Lebanese immigrants between 1922 and 1949. We are using death certificates, national mortality statistics, and census data to compare the prevalence of influenza, pneumonia, tuberculosis, heart diseases, and cerebrovascular diseases (stroke) among Lebanese American communities and the general United States population [2]. Our research suggests that from 1922 to 1949, Lebanese immigrants had a higher rate of death than the general US population. During this period Lebanese immigrants passed away at a rate of nearly 13 per 1000 while the general American population maintained a death rate of around 10.5 deaths per 1000. This higher death rate among Lebanese Americans may be attributed to a couple of factors: an aging immigrant population with a small percentage of children and infants, and drastic changes in diet and lifestyle as they entered the middle class. The first factor is a function of the nature of migration. Specifically, the majority of Lebanese who immigrated to the US between 1880 and 1920 were teenagers and young adults. Thus, by the 1930s and 40s, Lebanese immigrants represented a clearly older community than the general US population, which helps explain their higher death rate. The George and Abraham families exemplify this trend [3]. In 1888, Joe Abraham (25) and Tom George (21) arrived in the US from the village of Maad, which is close to the city of Jbayl, Lebanon and settled in Thurber Junction, Texas. In 1908, Tom’s sister-in-law Tyla (36), left her husband and youngest children in Lebanon, and immigrated with her eldest daughters, Myra (21), and Arslie (18). Tyla’s husband Tony (43) then joined them with their remaining four children (ages 7 to 16) in 1913. Typical of many immigrants, the George and Abraham families included 6 adults and only 4 children. This contrasted sharply with the average American family which counted within it many more children, and explains why there was a higher rate of death amongst these early immigrants.

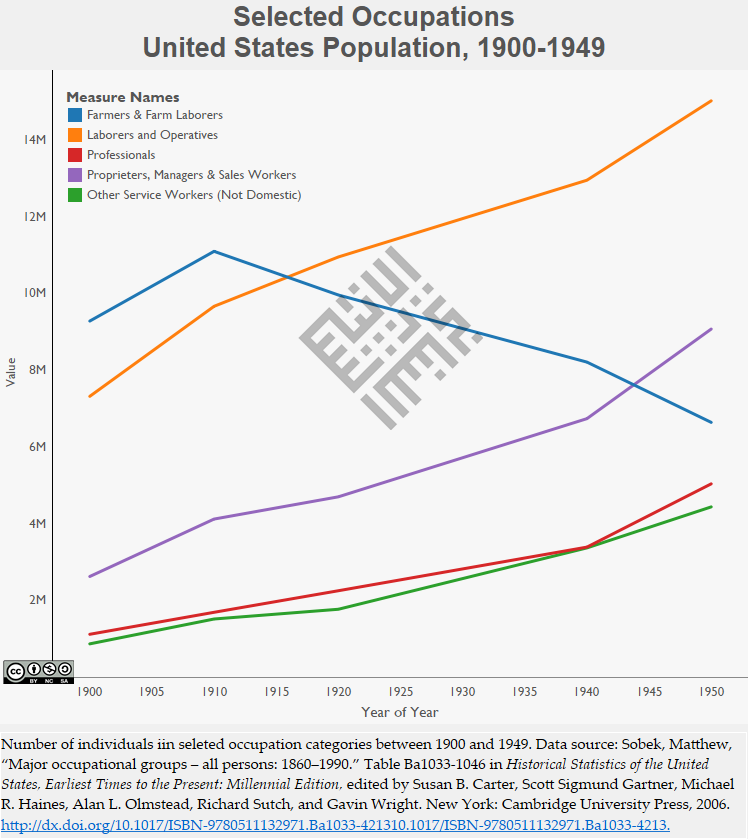

However, the demographic spread of migrant families does not entirely explain the higher death rate among Lebanese immigrants. It is quite possible that changes in work environment contributed to a greater risk of heart disease and stroke amongst these early immigrants. By 1935, Lebanese Americans were more likely to die of heart disease than the general US population. Throughout the first half of the 20th century the rate of death due to stroke within this community also remained slightly higher. In the 1920s and 1930s, Syrian immigrants transitioned from physical jobs like peddling and factory work to mercantile businesses. Following this trend, in Thurber Junction, Joe Abraham and Tom George peddled together in the early 1900s, but by 1910 they each owned a dry goods and grocery store. Their stores catered to a growing mining community of over 1000 people. As their families joined them in the US they had more support operating their stores. Tom’s nieces Myra and Arslie worked as saleswomen in his store, while their mother peddled. Both Joe and Tom’s stores became family businesses and many of their children and grandchildren also became merchants. Their increasingly sedentary lives as merchants and store clerks could have increased the risk of heart disease and stroke. Out of the nineteen members of the Abraham and George families to die with accessible death records for Texas (1903-1982) eleven died of heart disease.

An article published in 1927 by the Lebanese American physician Dr. Haickel Elkourie (who lived in Alabama) attests to this shift within the larger community. In it, Dr. Elkourie raised concerns about the prevalence of obesity among Lebanese immigrants. He argued that their richer meal habits and the little exercise they did in America–compared to their physically rigorous village life–led to overweight and health problems associated with it. Middle class Lebanese Americans, like the Abrahams and Georges, gained unprecedented access to food in the US. In hamlets across Mount Lebanon like Maad, villagers’ diets consisted mostly of vegetables and legumes, such as lentils. Moreover, they had sparse access to meats, rice and sugar, all of which were considered luxury items beyond their day to day means. In America, their diet changed dramatically. Elaborate and heavy foods traditionally consumed in villages on rare holiday feasts, quickly became a weekly or nightly meal in immigrant’s middle class homes. A column titled “Favorite Syrian Recipes” appeared regularly in The Syrian World in the 1930s and demonstrates this shift in diet. In these recipes, writers adapted light Lebanese dishes to include several pounds of lamb and rice, and thus the “Mediterranean” diet became Americanized. New eating habits that infused old recipes with new and richer ingredients, led Dr. Elkourie to offer readers three points of advice for avoiding obesity: “Exercise frequently to a point of profuse perspiration, avoiding extreme fatigue,” “Avoid heavy evening dinners and particularly sweets and fats after 6 P. M.,” and “Use whole wheat bread exclusively, and drink large quantities of water [4].” Elkourie suggested that shifting from traditional and sparser modes of consumption into mass consumption, and the transformation of recipes, put immigrants at greater risk of heart disease in America.

On the other hand, the Lebanese immigrants initiation into middle class life had some health benefits. Our data indicates that a move from packed tenement housing into more spacious middle class homes, and from factory floors teeming with workers and ill-winds into the airier environment of stores and shops, had positive effects on health. As the Lebanese American middle class grew between 1922 and 1949, fewer died from influenza, pneumonia, and tuberculosis than the general US population. This directly correlates with a decline in the number of Lebanese migrants laboring in factories. For instance, in Thurber Junction, the first four members of the George and Abraham families to pass away, died of Tuberculosis and Influenza while all subsequent deaths in the family were due mostly to heart disease. As the coal mining industry in Thurber collapsed the family may have been less exposed to communicable disease due to changes in the community around them. The emerging Lebanese American middle class may have also had better access to health care. The decline in peddling, a career that lacked stability, and transition to physically and financially settled jobs such as proprietors of stores and restaurants suggests easier access to hospitals in times of illness. However, this remains a speculation that is not always supported by anecdotal evidence. For instance, articles in The Syrian World indicate that many immigrants did not regularly visit physicians. In an article titled, “Health Problems of the Syrians in the United States,” Dr. F. I. Shatara, a doctor from New York, urged Syrian Americans to take better care of their health. Shatara, who emigrated from Lebanon in 1914, encouraged immigrants to adopt modern health practices, like routine examinations, and stated, “My plea to the reader is simply this―treat your body as well as you treat your automobile, for while you can easily buy a new car, medicine has not yet progressed to the point where it can give you a new body if you wreck the one that God gave you [5].”

Reverend W. A. Mansur, who immigrated to the United States in 1900, also urged immigrants to seek better health care. The Protestant minister wrote in The Syrian World that Lebanese Americans must “Guard …[their] health according to the best methods in hygiene and medicine.” While the growing Lebanese American middle class may have had better access to healthcare, Shatara and Mansur’s concerns demonstrate that immigrants did not readily adopt routine health examinations [6]. Nonetheless, if middle class immigrants were not apt to schedule yearly exams, in times of illness they would have been more able and likely to seek out medical care when in the past the itinerant nature of their work made house calls or hospital visits more difficult. This, in combination with overall improved living conditions, could account for the notable drop of communicable diseases (like tuberculosis) at the same time that lifestyle diseases (like heart disease) rose. Surprisingly for the George and Abraham families, the older generation (Tom and Tony George and Joe Abraham and sister Nacema) lived longer than their children who had arrived in the US as teenagers. On average the older generation lived to age 70 while their children died on average at age 57. While these families do not necessarily represent all Syrian immigrants, their story and our research reveals how migration impacted immigrant health. Explore the graphs here and observe how the prevalence of influenza, pneumonia, tuberculosis, diseases of the heart, and cerebrovascular diseases compare between the Lebanese immigrant and US populations. The graphs of the immigrant population appear erratic compared to the general US population graphs because there are less records in the Lebanese death certificate collection. You can read more about health and migration and explore interactive maps on our website.

Sources

[1] From title- While early immigrants identified themselves as “Syrian,” the vast majority came from a region that makes up modern Lebanon. Moreover, the term “Syria” was geographical rather than national.

[2] Khayrallah Center data currently represents eighteen states: Arizona, Kentucky, Missouri, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, and West Virginia. You can find more information on the scope of the Khayrallah Center’s death certificate database on our website.

[3] Researchers randomly selected to examine the George and Abraham families of Thurber Junction, Texas.

[4] H.A. Elkourie, “Progressive Medicine,” The Syrian World 1, no. 7 (January 1927): 34-36.

[5] F. I. Shatara, “Health Problems of the Syrians in the United States,” The Syrian World 1, no. 3 (September 1926): 8-10.

[6] W.A. Mansur, “The Future of Syrian Americans,” The Syrian World 11, no. 3 (September 1927): 11-17.

- Categories: