Archive Spotlight: Basil M. Kerbawy, Early Lebanese American Historian and Advocate

This post is written by Claire Kempa, a MA student of Public History at NC State University. At the Center, she works on the digital archive and on Mashriq & Mahjar: A Journal of Middle East Migration Studies. Read more about this archival resource and the community member who donated it after the article!

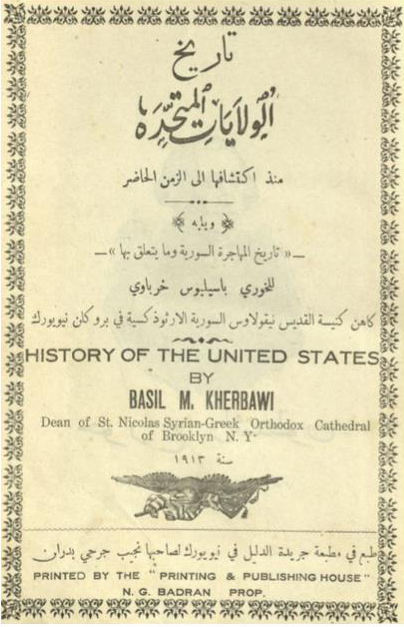

One of the most exciting additions to our Digital Archive is The History of the United States and the History of Syrian Emigration by Reverend Basil Moses [Kherbawi] Kerbawy. The History of the United States and the History of Syrian Emigration was published in 1913 in Arabic for an immigrant audience. The first section, The History of the United States, is an account of American history through a distinctly immigrant perspective. While much of this section of the book is a synthesis of American historians, it provides fascinating insights into the immigrant perspectives towards Native Americans. The shorter section of the volume, The History of Syrian Emigration, provides an account of Syrian immigration from an Orthodox Christian perspective. This richly-illustrated portion of the book contains numerous biographical details about the rising bourgeoisie class of early Lebanese and Syrian Americans, including lists of rising professionals such as doctors, authors, and merchants who lived across the country. Together, this double volume is a potential goldmine for both scholars, genealogists, and researchers. [1]

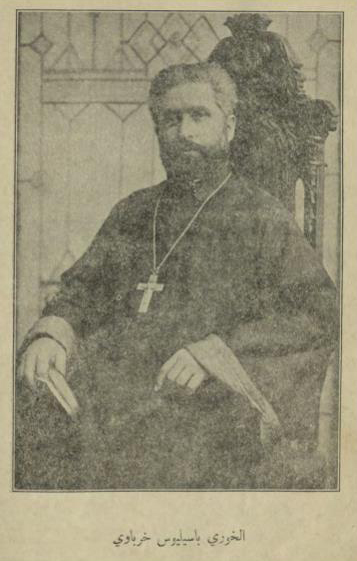

Reverend Basil Moses Kerbawy, the author of the volume, was a prominent writer, religious leader, and community member of the first wave of Lebanese American immigrants. Kerbawy was born on November 12, 1872 in modern-day Tyre, Lebanon. He attended the American University of Beirut and served at the Presbyterian Seminary for Boys in Antioch, Syria, before immigrating to the United States in 1899. [2] After serving at a parish in Toledo, Ohio, Kerbawy and his wife Zakia, settled in Brooklyn, where he obtained a position at the St. Nicholas Syrian-Greek Orthodox Cathedral of Brooklyn, New York. As Archpriest and Dean of the Orthodox Church, Kerbawy was deeply embedded in the Syrian community of New York City: notices in The Syrian World suggest that he presided over numerous baptisms and funerals for New York immigrants throughout his thirty years of service, and he was an active community organizer outside of the church. [3]

Uncovering early immigrants’ personal experiences of and reactions to prejudice and oppression can be a challenging task for researchers. Because of his prominence as a writer and public figure, Kerbawy left behind documents that provide insight into this oft-buried aspect of the immigrant experience. In April of 1911, he wrote to William Gaynor, then mayor of New York City, to request protection against harassment, a letter that is worth quoting in full:

“Most Honored Sir — I want to know if it is a crime to wear a beard? I suppose that this may appear to be a foolish question to you, but to me it means a great deal. I am the pastor of St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox church on Pacific street, Brooklyn, and my profession calls for the wearing of a beard. When I got out on the street the boys and young men mistake me for a Jewish rabbi and insult and assault me.

They often throw decayed vegetables at me. If I were a rabbi, would that be an excuse for loafers to assault and insult me? I am a citizen and as such should be protected from assault.

I have borne the insults and assaults patiently up to last Saturday night, when an incident occurred that made me lose all patience. I was alighting from a car at Seventy-third street and Thirteenth avenue, Brooklyn, when a little loafer hit me with a decayed vegetable, which I believe was a more than ripe tomato. This exhausted my patience. I went for the lad, who, luckily for him, escaped.

Hoping that you will do what you can for me and gain for me the protection I deserve, I am sir,

Very respectfully,

BASIL M. KERBAWY.” [4]

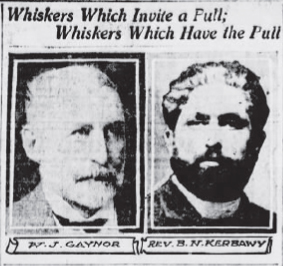

Remarkably, Major Gaynor responded to Kerbawy’s plea for assistance. However, his response fixated on Kherbawy’s rhetorical opening question—“Is it a crime to wear a beard?”—more than it did the injustice of the attacks themselves and the underlying prejudice that likely motivated them. “It is not a crime to wear a beard,” Gaynor replied, “I wear one myself and nobody ever takes any notice of it.” Gaynor goes on to imply that Kerbawy was somehow at fault for the abuse, asking:

“How is it they take notice of your beard? Have you trimmed it in some peculiar way, contrary to the Scriptures? For you know the Scriptures say, ‘Ye shall not round the corners of your heads, neither shalt thou mar the corners of thy beard.’”

While seemingly sympathetic, embedded within this question is the assumption that Kerbawy’s “peculiar” Christianity—as opposed to the mayor’s own mainstream and superiorly-informed Christianity, which he demonstrated through a Scriptural reference—was at fault for the abuse that Kerbawy received. Nonetheless, despite his implication that Kerbawy invited insults and hurled objects through his “peculiar” appearance, Gaynor offered support to the reverend in the form of a police escort at least “for a few days until we arrest some of those who are wronging you.” [5]

The letter, and the mayor’s response, were picked up and syndicated by newspapers across the country. Following the tone of Gaynor’s letter, the reporting centered on speculations about the nature of Kerbawy’s beard. While this might, to a modern reader, seem like a frivolous use of newsprint, in fact it reveals that appearance was a central factor in distinguishing an ‘American’ from a ‘foreigner.’ The wide distribution of the story—which was reprinted everywhere from Raleigh, North Carolina, to Salem, Oregon—signaled to readers that, while violence was condemned, visible signifiers of ‘foreignness’ were nonetheless unwelcome on the streets of New York City—or any other city in America. The tone of the reporting was often mocking and hyperbolic, and the speculations about Kerbawy’s appearance were so pressing that The Evening World visited Zakia Kerbawy at their house and obtained a photograph of Kerbawy and his famed beard to print in their own paper. While this presumably satisfied the audience for the story, it may have also been disappointing, for the unnamed reporter, presented with photographic evidence, was compelled to describe Kerbawy as “a well-set-up man of modern manner and dress, and wearing a beard no longer than Mayor Gaynor’s.” At the time of the interview with Zakia, Kerbawy had not yet taken up Mayor Gaynor’s offer of police protection; however, Zakia asserted that the mayor’s response would function as a sort of armor for the reverend: “Now, if anyone bothers him, he will just show the letter, so that the person will know that he is likely to be punished!”[6]

While Kerbawy’s widely-reported act of self-advocacy brought him a brief moment of fame throughout the country, his whole life was devoted to improving the lives of Syrians and Lebanese both in the United States and at home. Kerbawy furthered his education at Columbia and Cornell, and became a well-respected lecturer on the history of the Orthodox Church. In addition to The History of the United States and the History of Syrian Emigration, Kerbawy published several other important and well received books for non-Arabic-speaking audiences: his contributions to the Episcopalian Church’s 1919 study of religion and emigration, Neighbors, provided early statistics on the numbers of Lebanese and Syrian immigrants, while his 1914 History of Russia was praised by Czar Nicholas Romanov.

These texts, and the History of the United States and the History of Syrian Emigration speak to Kerbawy’s importance as an early intellectual and historian. However, Kerbawy’s letter to Mayor Gaynor is an equally powerful legacy of advocacy and activism. Though Kerbawy was a well-educated and well-known figure, his privilege did not protect him from abuse; however, his command of English and his position as a priest enabled him to take the unusual measure of protecting himself through legal means. As remarkable an insight as this story is, the available newspaper evidence suggests that Kerbawy’s expression of agency and determination against prejudice was not an isolated incident, but rather a lifelong practice, and one which he extended to the protection and betterment of the worldwide Lebanese and Syrian people. Mere weeks before his death in December of 1947, Kerbawy was deeply involved in organizing a public campaign to raise money to aid victims of flooding in Syria. [7]

About the book

This copy of the book belonged to Joseph and Rose El-Khouri, and was lent to the Khayrallah Center for digitization by their daughter Marsha El-Khouri Shiver. Other material belonging to the family is available in the El-Khouri Collection on our Digital Archive. Books, like this one, passed down through generations provide great insight into the lives of Arab Americans from the past into the present. If your family owned a copy of one of Kerbawy’s books, or a similar volume, please email us at lebanesestudies@ncsu.edu to share your story and help us build our understanding of the experience of immigration.

Sources

[1] Kherbawi, Basil M. The History of the United States and the History of Syrian Emigration.

[2] “Rev. B.M.Kerbawy Funeral Saturday.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 1, 1947. Accessed February, 2016 through newspapers.com.

[3] “Dean B. Kerbawy Honored at Dinner.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. June 14, 1947. Accessed February, 2016 through newspapers.com.

[4] While this letter, and its responses, were widely reported in newspapers around the country, I was first made aware of the story by historian of Orthodox History Matthew Namee. Namee, Matthew. “To Shave or Not to Shave?” Orthodox History: The Society for Orthodox Christian History in the Americas. Blog. December 11, 2009. Accessed January, 2016. http://orthodoxhistory.org/2009/12/11/to-shave-or-not-to-shave/.

[5] Gaynor, William J. Some of Mayor Gaynor’s Speeches and Letters. New York: Greaves Publishing Company, 1913.

[6] “His Beard Saved from Hoodlums by Gaynor’s Letter: Brooklyn Priest Certain Missive Will Ward Missiles Off in Future.” The Evening World, April 27, 2011. Accessed February 2016 through newspapers.com

[7] “Syrians Ask Help for Flood Victims.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 24, 1937. Accessed February, 2016 through newspapers.com.

- Categories: