The Chasm of Assimilation – My mother’s New Zealand cousins

This article is written by Cecile Yazbek who was born into a Lebanese family in East London, South Africa. She is the author of four books all related to the Lebanese diaspora. This is the first in a three-part series including Albinos and the Lagger and Transplanted Family Trees. All photos courtesy of author.

New Zealand Rules

In New Zealand in 1899, an English language test was applied to all migrants of non-Irish or British origin. In 1920, the Immigration Restriction Amendment Act provided that 98% of immigrants should be of British origin. The Lebanese remained classified as Asiatics, disqualified until 1930 from access to pensions or family allowances. In 1974, New Zealand finally introduced a non-racist immigration policy.

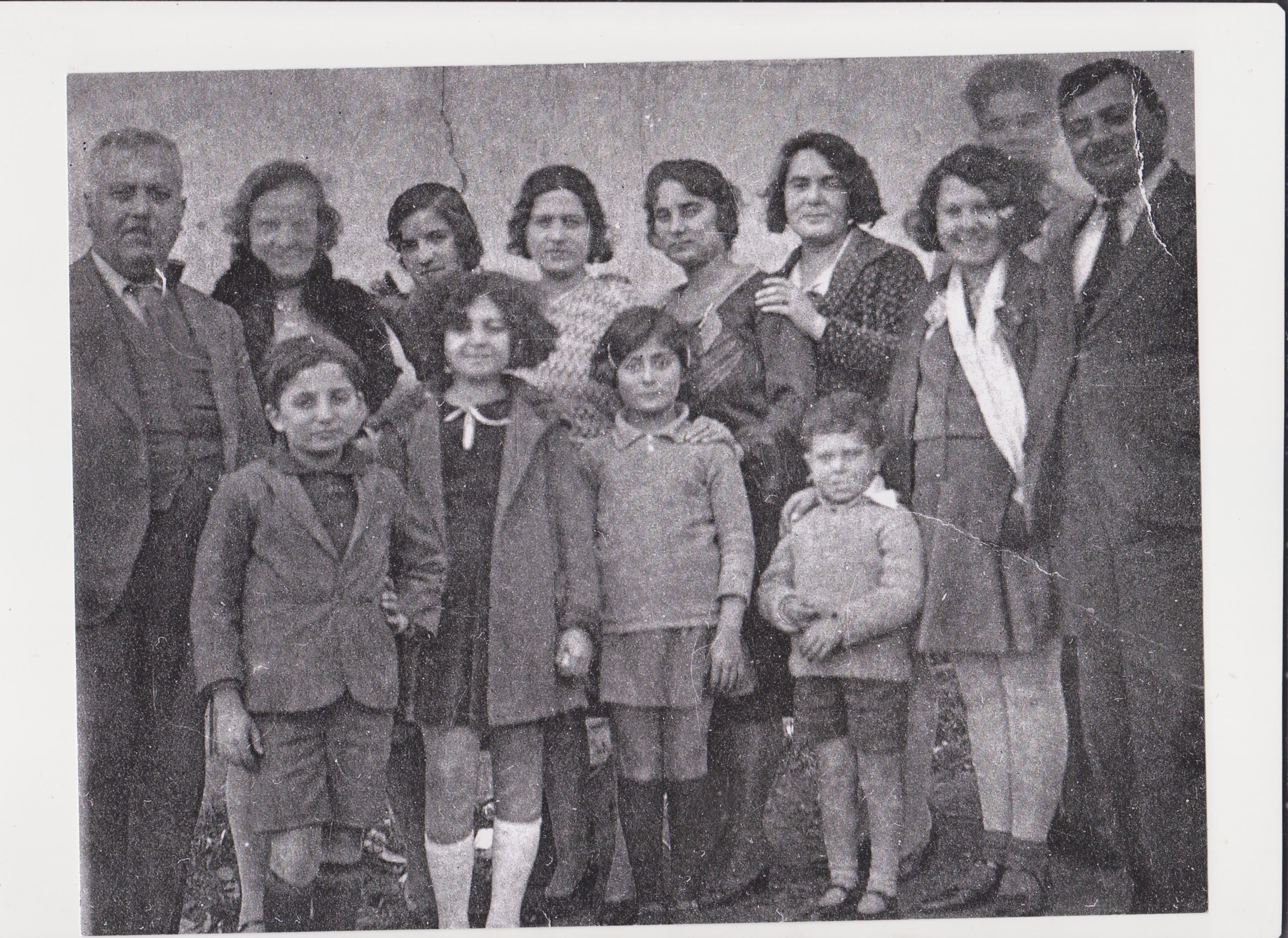

The Haddad-Akel Families

In 1910, my mother’s aunt, Nabeeha Haddad and her husband, Joseph Akel, left Lebanon for New Zealand. When the First World War broke out in 1914, Joseph took his wife and children back to Lebanon in order to join the British war effort. He worked with General Allenby and acted as a translator for T.E. Lawrence. Joseph’s nephew, Norman was a runner in the Arabian Desert.

In 1922, my grandfather, Alexander Haddad took his family from South Africa to Lebanon for a year. There was a joyful reunion with the New Zealand family; the children attended school in Beit Meri together.

A year later, the Haddads returned to South Africa and the Akels to New Zealand. Over decades the cousins exchanged letters and photographs.

In Australia, 1990

My mother in South Africa wrote to me that her cousin, Lili had moved to Australia from New Zealand. She gave me contact details for Lili’s niece, Dee. We met in Sydney. Her features resembled my mother’s siblings, awakening my longing to resume a cousinly conversation that had ended when I left South Africa. But Dee shied away from my Lebaneseness. I asked to meet Lili but she described Lili as, ‘English now’. In response to my offer to prepare some family recipes, Dee said, ‘What recipes? We prefer a lemon sole.’

It took me ten years to get past Dee, the gate-keeper – I finally met Lili before her ninetieth birthday. On a bright winter’s day, I drove across Sydney, a jumble of emotion. Was I English enough? Was I too Lebanese? My handbag was stuffed with photographs: my mother and her older sister Phyllis in their seventies, my siblings and our cousins. My head brimmed with decades of Haddad history.

At the front door of her home, an erect white-haired lady grabbed my hand excitedly. ‘I never had any relatives in Australia.’ I feasted my eyes on Lili, as much Haddad as myself.

Groups of our enormous extended family from towns and cities in South Africa would have given a limb to sit where I sat that morning. I asked Lili, ‘How was it in New Zealand with Lebanese parents?’

‘We were not allowed to speak Arabic at all. My elder brother insisted we spoke English. My father wanted us educated. On Sundays, we had to memorise a poem, or a quote from Shakespeare, and line up in front of him to demonstrate what we had learned in school. We were happy.’ New Zealanders, instead of nondescript foreigners. It sounded like that migration language test.

‘Did you feel Lebanese? Did you eat the food?’

‘Yes, I remember some Arabic prayers. My mother cooked stuffed vegetables but my Scottish husband preferred plain food.’

In a cross-cultural marriage, her culture was deeply buried. Perhaps in the folds of her brain there could be some Lebanese fragments. She didn’t need them, but I longed for their familiarity.

Lili’s daughter joined us. ‘They hid their origins; it wasn’t even mentioned. In fact, my mother’s youngest brother Fred, an orthodontist in Harley Street, attending to the teeth of royalty from east to west, never told anyone he was Lebanese.’

My pleasure in meeting Lili was tinged with sadness for my mother who had visited England at various times and tried in vain to meet Fred. ‘What’s wrong? Is there something shameful he doesn’t want us to know?’ If my Middle Eastern-looking parents had appeared, announcing their kinship, Fred’s cover would have been blown. No, Mother, nothing was wrong, he had decided to be English.

Acquired Differences

On first meeting those Lebanese New Zealanders, I felt our genetic similarity, but found differences in our identifications. The Lebanese in South Africa clung to the church that had won them their citizenship. Albeit in private, we retained our recipes and fragments of language in large family gatherings.

Early Lebanese migrants to New Zealand lost motherland and mother tongue. Echoing the Immigration Restriction Act, shame about their origins reached into people’s psyches, dismembering their pasts and connections. My cousins carried no Arabic, no recipes beyond memories of Nabeeha, who took the bus across town with a tray of kibbe to visit someone who was ill.

In the countryside

I recently accompanied Lili’s daughter to visit Dee, the gatekeeper, on her country estate.

I mentioned the family history that I was writing and she announced that being ‘English now’, she was no longer interested in historic family. ‘Do your neighbours know your origins?’

Wide-eyed, she shook her head.

‘You look more Lebanese than I do.’

‘I tell them about our Greek ancestor.’

Lili’s daughter, who had been listening, said, ‘Lebanon is a joy: the food, the people, the country, it’s fabulous. We’re dying to go back.’

Dee shook her head again. This cousin who is genetically as Lebanese as myself made me feel as if my origins were a secret stain that I carried into her home.

Outside we strolled across paddocks, towards glassy ponds in which black swans glided. A light breeze teased the tops of the ghost gums, where black cockatoos called. On the way back to the house, a few residents were chatting in the lane. ‘Remember, we’re Greek – Kalimera – it’s good evening, I think.’

My mind roved far and wide, through decades of Dee’s personal losses and around the vineyard to find reality. I saw her cocooned from sadness inside her house, where everything matched and gleamed. Once she told her neighbours the truth of her origins, she thought the elegance of her home would be viewed as a borrowed façade, a disguise for her ‘unsavoury’ Lebanese identity. Her personal history was trammelled with racial shame.

All night the wind banged and shrieked. At breakfast, like a big bad wolf, the gale still howled, forcing itself through chinks and window frames as if propelling truth into the house, to set her free at last.

Further Reading

Hage, Ghassan. Arab–Australians Today: Citizenship and Belonging (Carlton South, Vic.: Melbourne University Press, 2002).

Malouf, Amin. On Identity (London: Harvill Press, 2000).

- Categories: