Transplanted Family Trees – In search of Yazbek: What makes us who we are?

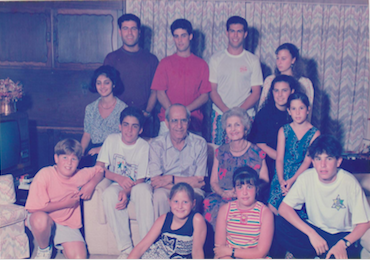

This article is the third and final installment written by Cecile Yazbek who was born into a Lebanese family in East London, South Africa. She is the author of four books all related to the Lebanese diaspora. Her other installments include Albinos in the Laager and The Chasm of Assimilation. All photos courtesy of author.

What makes us who we are?

On a quest to link the scatterlings of my family who emigrated from Lebanon to South Africa, New Zealand and South America, I pick among spectres and shadows, searching for our history in faded paper squares – nameless and dateless photographs in moth-eaten albums. In our relocations with transliterated names, painful gaps in knowledge reaching back less than three hundred years, make the assembly of an accurate history and family tree a process filled with emotion. We are dispersed to the four winds, some never to be known.

Our little and big world

In the 1960s, my father’s brother Victor and his wife Freda took a cruise from Cape Town to Rio de Janeiro. Wandering among elegant waterfront shops, they went into a jewellery store. When Freda admired a few pieces, Victor said to her in Arabic, ‘Too expensive.’

The shop assistant erupted, ‘Do you speak Arabic? Where are you from?’ Having established that they were related, a crowd of Brazilian Yazbeks mounted a banquet to welcome the visitors.

Not long after that, my parents visited Hadeth, Beirut to meet my father’s first cousins. His uncles wore the honorific tarboosh while the children celebrated education as lawyers, doctors and dentists.

The following year, a pair of cousins visited us in South Africa. On Sunday, our Lebanese relatives accompanied us to mass in our parish where my father sat loudly in the front row. The exuberance of reunion still rings in my ears.

Then war smashed everything in Lebanon – our cousins went to France, Cyprus, the United States and contact was lost, due in no small measure to the devastation of their homeland and a family casualty. Overseas, we were powerless to help except with financial offerings that probably fell into someone’s war chest.

I migrated to Australia in 1986 and searched in the Lebanese community for Yazbek relatives but found no Christians or city dwellers, the two main features of my father’s family.

In 1999, a South African cousin took his mother at last to Lebanon. Weeping the tears of exiles, they walked the ancestral stones. In Hadeth, Beirut on a quest for Yazbeks, they were told, ‘Oh, you are looking for the converts.’ My cousins shrugged and travelled on, delighting in scenery, familiar foods and shrines.

People of the Cedars, purporting to be a comprehensive guide to South Africa’s Lebanese community, was published in 2011. Yazbeks in South Africa are a vast, multi-generational, educated and socially engaged clan. This is how we were described: ‘The Uzbeks are of Russian, Persian, Afghan and Arabic origin…originally…Sunni Moslem.’ I was shocked to see these few lines about the Yazbeks, when smaller families spanned pages.

Ottoman engagement

My cousin, Dr. Ivor Yazbek drew up an extensive family tree and traced our line back to around 1800, when Yazbek, one of five sons, was born.

My great-grandfather Tamar Yazbek (born 1840), lived in the palace of the Ottoman rulers in Beirut as their language teacher. This raised questions about his ancestral religion. When he was widowed in 1882, the Ottomans gave him a twelve-year-old girl, Emily Azerach from Constantinople, as a gift. In 1910, he took her to Africa where he died, leaving her with eight children, two from his first wife.

Tamar and Emily’s eldest daughter, Farida, married Antoun, son of his brother, Boutros, a Maronite priest. These are my grandparents. Our Christian heritage seems clear. But the South African book suggests that, unlike the rest of the community, Yazbeks are not direct descendants of the Phoenicians and have no Christian lineage. Some family members are outraged by the idea of an origin other than Catholic, their religious zeal disdainful of non-Christians and Protestants alike.

Me and You = Us?

Belonging, more personal and individual than identity, contains a sense of feeling included, of being at home. When I accept the disparate parts of the person I am, I communicate this to you and give you the space to be the person you are. Then we are in contact with our shared humanity. Amin Maalouf expands this idea. ‘For it is often the way we look at other people that imprisons them within their own narrowest allegiances. And it is also the way we look at them that may set them free.’

This view seems to underpin ‘Peter Singer’s theory of the Expanding Circle – the optimistic proposal that our moral sense, though shaped by evolution to overvalue self, kin and clan, can propel us on a path of moral progress as our reasoning forces us to generalise it to larger and larger circles of sentient beings’.

My father’s Lebanese culture and over-arching Catholic belief in the equality of all, gave him courage to act against apartheid in public life in South Africa.

The welcome by those Yazbeks in Brazil exemplifies Lebanese hospitality. Their strong identification with their origins imparts a sense of belonging to strangers in the diaspora, and enables them to accept all who cross their path, regardless of religious affiliation. Is this capacity enhanced by their situation in an inclusive society? In a society riven by race and religious division, such as South Africa, does internalised racism promote people’s quest to identify with a unique ancestry such as Phoenician or Pharaonic that sets them apart and gives them an inner acceptance for physical features not shared with the dominant group?

A cousin in South Africa had his DNA sequenced to find out that he was ‘70% French, some Iraqi, plus…’ In the light of current racial profiling, will he carry that piece of paper on his person for display or concealment depending on where he travels?

Because of my South African apartheid experience of exclusive identities, I deliberately claim no adherence to any sect. I prefer to express the inclusive hospitality of my Lebanese origins and the social justice brand of my upbringing. It is the security and breadth of my cultural identification that enables me to reach out beyond the confines of expedient labels.

Sources

Hage, Ghassan. White Nation. London: Pluto Press, 1998.

Hanna, Ken and Charbel Habchi. People of the Cedars. South Africa, 2011.

Malouf, Amin On Identity. London: Harvill Press, 2000.

Pinker, Steven. “The Moral Instinct.” The New York Times. January 13, 2008

Further Reading

Thich Nhat Hanh was a Vietnamese monk, Buddhist teacher, poet, and Zen master. He was the author of 25 books translated in many languages.

Dr. H.I. Yazbek private archive. South Africa.

- Categories: