Visible at Last

This article is written by Cecile Yazbek who was born into a Lebanese family in East London, South Africa. She studied social sciences at Rhodes University and moved to Australia in 1986 where she continues to write. She is the author of four books all related to the Lebanese diaspora. In 2016, she published a three-part series for the Khayrallah Center including Transplanted Family Trees, The Chasm of Assimilation, and Albinos in the Laager.

‘For it is often the way we look at other people that imprisons them within their own narrowest allegiances. And it is also the way we look at them that may set them free.’

-Amin Maalouf, On Identity

In writing our lives, we find a starting point in a memory or an experience, something we feel it is important to document. As a child, growing up under apartheid in South Africa, there were things I observed for which I had no words.

When I arrived in Australia at the age of 33, I found myself in a similar situation – seeing things that I couldn’t explain because I didn’t share a history with the Anglo-Australians among whom I had landed. Because I spoke and understood African languages as well as Arabic, I felt separate, marginalised, from other white South Africans who had migrated to Australia.

Aware of how distance altered my position in the psychic landscape of family and friends, but also gave me freedom and perspective to construct memory in a coherent way, I took up my pen to write my bittersweet memories, unaware of how difficult it would be to have anything Lebanese published in Australia.

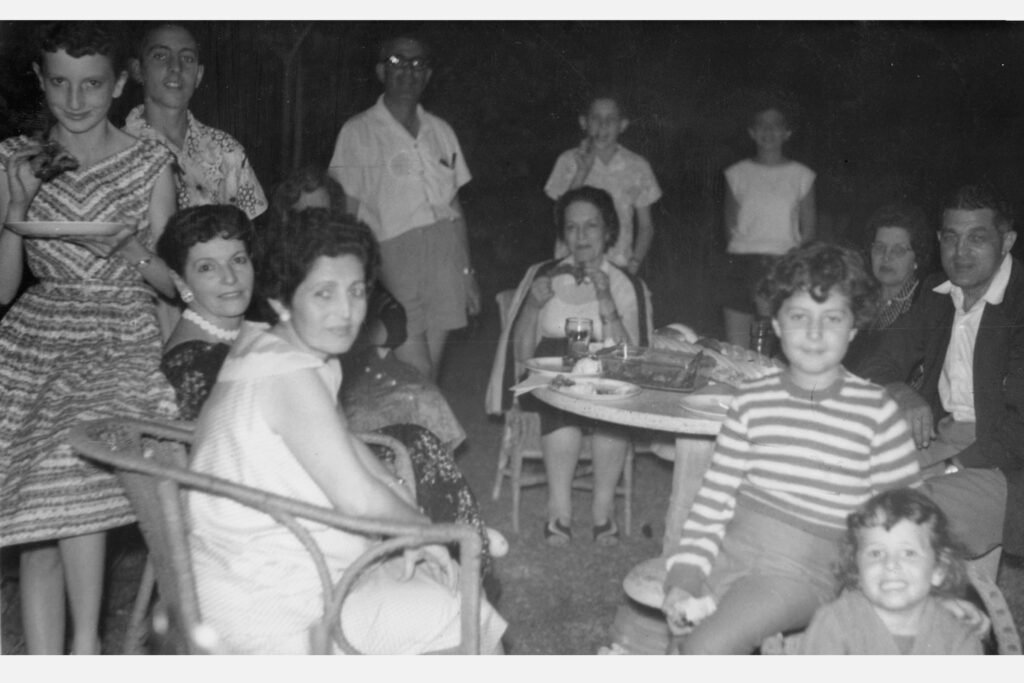

In South Africa, our community of extended family had gathered on weekends to celebrate our culture with foods and fragments of Arabic language that we kept concealed when we went out in public. In our enclosure of privilege within a sea of racially legislated segregation and poverty, we had an identity connected to the culture of our ancestors. We lived as Lebanese inside the house and were as assimilated as our physiognomy allowed in the street – a construct of ‘multiple inhabitance,’ common to migrants – except we were within our country of domicile. Because of this disconnection from the wider society, we feared behaving in ways that threatened our integration (Ghassan Hage, 90).

I write about the Lebanese in South Africa to remind us that we have a country of origin, with cousins in Lebanon and across the globe.

My maternal grandmother was the only living ancestor in my family when I was born and, like her sons, practised no religion. On her last visit to Lebanon, she rushed back to South Africa saying there were ‘too many Lebanese over there.’ Aside from her descriptions of glorious mountain and sea vistas, she had no longing to re-create that place in South Africa. Her family constituted her world.

Ten years later, my parents travelled to meet our Yazbek relatives in Beirut. Tearful visits and joyful reunions in ancestral homes began a connection that continues down the generations.

In Australia, I assumed that, because our foods appeared in the marketplace, we had become acceptable. But it wasn’t long before I encountered disdain, even contempt, for things Middle Eastern and Lebanese. In a Lebanese shop, discussing ba’lie with the grocer, a woman waiting in line could no longer contain herself, ‘What, you proud to be Lebanese? Others say they’re Greek or Italian.’ I refuse to hide.

Some Lebanese South Africans living in Australia feared contempt and announced, ‘I am South African,’ with a downward inflection that did not invite further discussion. Others were ashamed and, with similar enunciation, claimed New Zealand origins.

In the early 20th century, my New Zealand cousins lived with silence about their origins. Their father banned them from speaking Arabic outside the house; they had to present perfect lives – ‘good enough’ for the society in which they’d settled. Their assimilation was fueled by shame and I wonder if this could be a source of anxiety in their descendants?

Ghassan Hage writes: ‘Diasporic anisogamy […] is foundational to the diasporic condition. […] The mere fact of being driven toward migration involves entering a relation of reciprocity with another people deemed superior’ (Ghassan Hage, 99).

Shame

As we age, we seek comforting memories. This fear, shame and inhibition to social participation concerns me.

In his book, In Defence of Shame, Tanveer Ahmad describes shame as ‘a pointer to a more primitive side of our nature, the parts our upbringing had a duty to civilise,’ and links this to anxiety in some of his patients (Tanveer Ahmed, 35).

Dr. Mireille Astore, in her thesis, writes that ‘recognition of feelings of shame can be the precedent needed for private as well as public resolutions to take place’ (Mireille Astore, 55).

In 2000, when Cathy Freeman ran an honour lap in the Sydney Olympics wrapped in the Aboriginal flag, the silence around the situation of Aborigines was broken.

Among Lebanese in Australia, shame is a tool of social control fuelled by gossip as well as internalised racism, which compounds the racism in the society, and fills the bearer with deep shame. Is it shame that prevents critical observation of our culture?

In 1990, when Nelson Mandela was released from prison and South Africa was unshackled, I had been in Australia for four years. Apartheid is regarded as a crime against humanity. Many bear internalised scars. Shame can paralyze but if it progresses to guilt, as I have seen in white South Africans of my age and older, reparative action can help the person to move forward.

Before

In the late 19th century my ancestors migrated from Lebanon to South Africa and were cut off from home except for an annual letter. They began their commercial enterprises as hawkers, peddling from farm to farm, across the interior of South Africa, like others across the world.

Because of the traumatic early deaths of their father and their grandfather within two years of each other, my father, as a boy of five, and his two sisters, spent seven years in an orphanage run by the Nazareth Nuns.

My mother’s father died when she was 12. The family lost everything. Seven years later, her brothers, and a number of other Lebanese men enlisted to fight in North Africa in the Second World War.

Subsequently, we integrated into the society, taking up educational opportunities available to us as white people. My mother’s brothers became medical practitioners, while lawyers proliferated in my father’s family. Still, we did not display our origins.

Dr. Guita Hourani has documented the legal battles of 1913 and 1925 by the Maronite Church in South Africa for Lebanese people to be granted the same full citizenship rights that accrued to those of European origin. The case was won on the basis of their Christian adherence, thus sealing their connection to the Church (Guita G Hourani).

In 1948, the National Party won power in South Africa. It formulated apartheid, a system of racial separation, enforced with draconian laws and penalties for transgression. The Lebanese feared the loss of their hard-won status in such a rigidly stratified, racialised society. Because of their questionable skin colour, new Lebanese migrants were no longer welcome to enter South Africa.

Landscapes

My lawyer father was reprimanded by the central authority when, as mayor of our town, he spoke out against the reservation of the best beaches for white people. Expressing the inclusivity of Lebanese culture and supported by his religious belief, he proclaimed that all God’s creation was for all God’s people.

The nationalistic fervour attached to the landscape by the apartheid regime was repugnant. Only when I had left that country and moved to Australia did I enjoy outdoor activities. But in Australia, a colony like South Africa had been, rivers run red with history.

My Books

‘The writer’s task is to be both public and private, an arbiter both of society and of the human heart,’ writes Salman Rushdie (Salman Rushdie, 110). What is in my own heart, I share with those of multiple, ancestral migrations.

In 2007, my memoir Olive Trees Around My Table: Growing up Lebanese in the old South Africa, describing my family and childhood in the shadow of apartheid, was published. An editor fought to delete my family history and other references to my Lebanese origins, wanting a ‘pure’ South African story.

Mezze to Milk Tart: From the Middle East to Africa in my vegetarian kitchen, a recipe-memoir came next.

Because of past silence about our history, I wrote Voices on the Wind, set in the small South African town where my mother’s family, the Haddads, battled social isolation and racial insecurity.

Faces in the Forest, is set in Cape Town in the 1970s, during the full horror of apartheid.

In Australia today, we with ‘funny’ surnames are, at last, being published, along with formerly invisible First Nations writers. Randa Abdel-Fattah, Sara Saleh, Michael Mohammed Ahmad, Omar Sakr spring to mind. Long before them, Professor Ghassan Hage published widely – and he continues to write and lecture around the world on race, nationalism, and identity.

Like Amin Malouf, I see my identity as fluid – a composition of many aspects including where I am, where I have been, what I came through, and in part, how I am seen.

Ageing, I feel at home in my family tree and the mini landscape of my garden. Once on the street, I realise that my formative history is somewhere else, forged as it was in the brutal time of apartheid.

Inspired by

Ahmed, Tanveer. In Defence of Shame. Redland Bay: Connor Court, 2020.

Astore, Mireille. Missing Lebanon: Art and Autobiography. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Western Sydney University, 2007.

Bayeh, Jumana. The Literature of the Lebanese Diaspora. London: I.B. Taurus, 2015.

Brown, Brené. Atlas of the Heart. New York: Random House, 2021.

Hage, Ghassan. The Diasporic Condition. London: The University of Chicago Press, 2021.

Hourani, Guita G. ‘The Struggle of the Christian Lebanese for land ownership in South Africa,’ The Journal of Maronite Studies 4.2 (2000)

Maalouf, Amin. On Identity. London: The Harvill Press, 2000.

Rushdie, Salman. Imaginary Homelands. London: Granta, 1992

Rushdie, Salman. Joseph Anton London: Jonathan Cape, 2012.

References

Amin Maalouf, On Identity (London: The Harvill Press, 2000), 19.

Ghassan Hage, The Diasporic Condition (London: University of Chicago Press, 2021), 90.

Guita G Hourani, ‘The Struggle of the Christian Lebanese for Land Ownership in South Africa,’ The Journal of Maronite Studies 4.2 (2000) webcitation.org/60Gu1gEbX.

Mireille Astore, Missing Lebanon: Art and Autobiography, unpublished doctoral thesis, Western Sydney University, 2007, 55.

Salman Rushdie, Joseph Anton, (London: Jonathan Cape London, 2012), 110.

Tanveer Ahmed, In Defence of Shame (Redlands Bay: Connor Court, 2021), 35.

- Categories: