Why did they leave? Reasons for early Lebanese migration

This article is authored by Dr. Akram Khater, Director of the Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies and Khayrallah Distinguished Professor of Lebanese Diaspora Studies, and Professor of History at NC State. It is part of a planned series of article that explore the early Lebanese immigrant experience. The first article in this series focused on who these immigrants were.

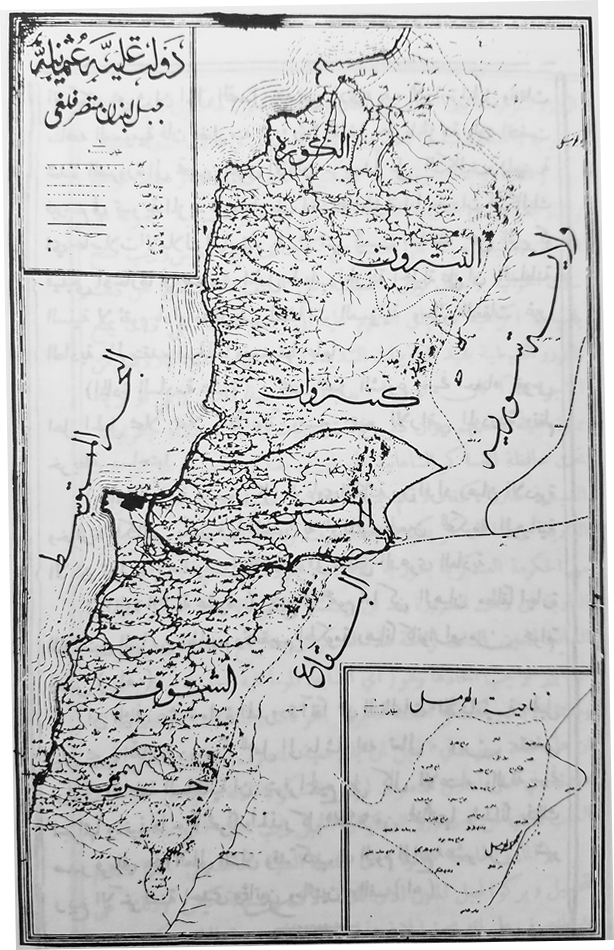

Why did some 330,000 migrants leave Bilad al Sham or “Greater Syria” (the lands that today encompass Syria, Lebanon, Palestine/Israel) between the 1870s[1] and the 1930s for the Americas?[2]

Previous Explanations

In the past, some have attributed this human movement to persecution of Christians, who made up a large percentage of the emigrants and mostly came from the central district of Lebanon, called Mount Lebanon. The story first then (and still told by some now) went something like this: oppression by the Ottoman government (which controlled the region), and attacks by neighboring Druzes (a heterodox sect of Islam) and Muslims made life untenable for these peasants and town folks and drove them from their homes. This story was developed originally by some of the newcomers themselves to elicit the sympathies of immigration officials at Ellis Island and facilitate entry to the US. Yusuf Bey, the Ottoman consul in Barcelona, remarked in an 1889 report to his government in Istanbul: “When questioned why they had to leave their homes in such large numbers, they invent …stories about the massacre of their wives and children … all to increase the compassion and thus the alms they can elicit.” Early immigrant writers like Abraham Rihbany, George Haddad and Philip Hitti further portrayed Christians in Mount Lebanon as defenseless victims of persecution oppressed by ruthless “Turks,” in order to garner support for their vision of an independent Syria and Lebanon. In resorting to this exaggerated narrative, they were feeding into Orientalist notions current at the time in America, which portrayed Islam and “Turks” (the term used for Muslims) as nefarious, violent, and repressive.

While we can certainly find incidents of violence and repression (neither of which was one-sided), the fact remains that the period between 1861 and 1914 was one of “long peace,” when, as the historian Engin Akarli argues, the inhabitants of Mount Lebanon—from where came the great majority of immigrants—enjoyed many advantages that nearby districts did not have. Amongst these were an elected governing council of Christians, Druzes and Muslims cooperating and feuding, a local gendarmerie (police force) that kept the peace, a rapidly growing infrastructure of roads, schools, waterworks, etc., thriving tourism, French political and military protection, lower taxes and exemption from conscription for Christians into the Ottoman army. The Russian consul to Beirut, Constantin Dimitrievich Petkovich, summarized this advantageous state of affairs in an 1885 report: “The current Lebanese administration has guaranteed for the Lebanese a greater measure of tranquility and social security, and it has guaranteed individual rights…With this it has superseded that which the Ottoman administration provides for the populations of neighboring wilayat [Ottoman districts].” An 1890 petition by Shi’a villagers from Jabal ‘Amil (in South Lebanon today), addressed to the British consul in Beirut, Mr. Eldridge, supports these contentions. In their letter the peasants requested Eldridge’s help in annexing their lands to the Mountain because “people there enjoy greater security, freedom and smaller taxes.” What corroborates these and many similar contemporary observations is that not all immigrants were Christian; in fact, many were Druzes and Muslims. For example, in the central Matn region of Mount Lebanon, villages records show that on average 18% of the Druzes’ population left, while only 12% of their Maronite counterparts emigrated. That not only Christians were leaving, and that there is no evidence of any sustained or systematic acts of oppression or violence during the height of immigration wave (1880-1914) casts serious doubt on the persecution narrative. Thus, and while there is no doubt that some individuals or even small groups left their homes because of persecution (real or anticipated), the great majority were not driven out by such matters.

Other commentators have argued, a little less frequently, that immigrants left the Levant to escape conscription into the Ottoman Army. This is an equally doubtful reason. Put simply, non-Muslims were in practice exempt from military service in the Ottoman army until 1909. In fact, there is no evidence whatsoever, beyond few Christians who served in the office corps, that any non-Muslims served in the Ottoman army before WWI. Despite the imperial reform edict of 1856 (known as Hatt-ı Hümayun) that equated Muslim and non-Muslim subjects of the Ottoman Empire, neither the Ottoman government nor the non-Muslim community were enthusiastic about conscripting Jews and Christians. For revenue purposes “the Ottoman state actually preferred that the Christians should pay an exemption tax (first called iane-i askerî – military assistance, and then bedel-i askerî – military payment-in-lieu) of their own, rather than serve.”[3] Even after 1909, when the Young Turks government tried to enforce equality in conscription, non-Muslims in Mount Lebanon retained exemption because of the special rule governing this particular Ottoman district. Recruitment of non-Muslims only began in earnest during WWI at which time emigration from the area had for all intents and purposes ceased.

Latest Scholarship

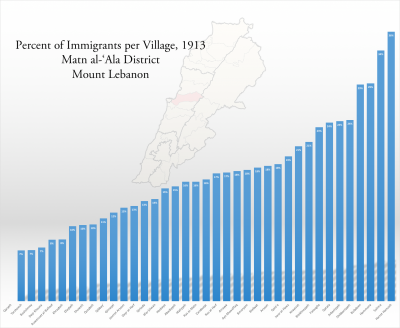

If sectarian persecution and/or conscription into the ranks of the Ottoman army were not the overwhelming reasons for emigration, then what prompted such a massive movement where anywhere from 15% to 50% of villages and towns emptied out? As one would expect there were many reasons for their decision to leave their loved ones and familiar places for a great unknown. Escaping a bad marriage (as did Gibran Khalil Gibran’s mother), reuniting with family, seeking adventure, pursuing learning and knowledge (as was the case with the Arbeely family), were all individual reasons to leave home. But while there was not a singular reason for the immigration of everyone, the majority left for economic reasons. They were part of the global Great Migration of the 19th century which saw the movement of millions leaving poor economic conditions from places such as Italy and Greece to countries in desperate need for labor like the US, Argentina and Brazil. In 1895 Mikhail As’ad Rustum, a famed Lebanese immigrant and poet, summed this up with these lines:

Now everyone desires to migrate To buy, sell and be a merchant

In a country replete with wealth Where the poor man can succeed

And in the early days, this process was easy to do from Lebanon[4]

Another contemporary observer from Mount Lebanon, Salim Hassan Hashi, wrote in 1908 that the causes of emigration were “to seek riches…in the farthest reaches of the inhabited world.”[5]

Or as Michael Haddy, a Lebanese-American recalled during a 1960s interview: “In 1892 not many people were going to America. This family went to America and they wrote back…[to say that] they made $1000 [in three years]…When people of ‘Ayn Arab saw that one man made… $1000, all of ‘Ayn Arab rushed to come to America…Like a gold rush we left ‘Ayn Arab, there were 72 of us…”[6]

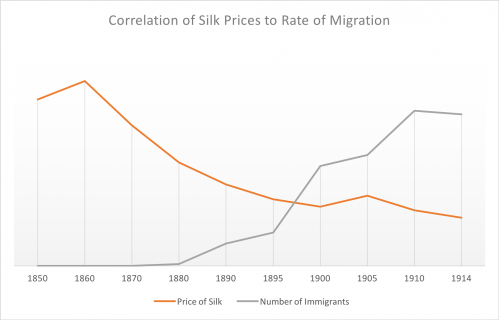

In other words, immigrants from the Eastern Mediterranean left limited opportunities in their homeland for better possibilities somewhere else to make money and then return home. Specifically, the stagnation and then collapse of the silk economy of Mount Lebanon (which accounted for 60% of the GDP of Mount Lebanon by the beginning of the 20th century), and textile manufacturing in the hinterlands of Greater Syria forced many to seek better livelihoods in the prospering lands of the Americas. This process began as with other parts of the nineteenth century world, when the Eastern Mediterranean attracted European capitalists seeking markets for their manufactured goods and sources of raw material for their factories. In the case of Mount Lebanon, it was silk—cultivated in its mountains since the days of Amir Fakhredin’s in the 16th century—that French industrialists sought for their factories back in Lyons and other cities. After few decades of boon, the prices of silk cocoons and threads stagnated and then fell in the 1890s. Compounding this problem was a series of bad crop years in 1876, 1877, 1879, 1885, 1891, 1895 and as late as 1909 that bankrupted many a peasant who had taken out loans against the anticipated crop. As the chart below shows, the drop in silk prices strongly and inversely correlates with the number of immigrants leaving Mount Lebanon for the US. Beyond the local economy of Mount Lebanon, the Ottoman Empire suffered from an economic depression lasting between 1873 and 1896. This severe downturn greatly affected small farmers and drove many of them to leave their properties in search of employment either regionally or across the world.

Finally, improvements in health care in Mount Lebanon (especially the introduction of vaccination) nearly doubled the population between 1860 and 1911 from a little less than 300,000 to more than 500,000 inhabitants. This dramatic demographic growth within two generations quickly outpaced the ability of the local economy to provide jobs and income. In short, the distress of local economies and simultaneous increase in the number of mouths to feed meant that peasants and townspeople from across the Eastern Mediterranean were sliding into poverty. By the early 1890s, as many silk factories were being shuttered, the decision to emigrate appeared as the most financially viable alternative for many.

This way out of impending poverty (for, generally speaking, only those with some money could afford to migrate) was facilitated by the presence of Western missionaries (particularly American Presbyterians) in the Eastern Mediterranean. Their schools and narratives of “Amirka” painted a prosperous image of the United States and allowed for the mental leap needed to depart from home and hearth. For example, Rev. W. A. Wolcott, a missionary in Beirut, recruited hundreds of workers for the textile mills in his native Lawrence, Massachusetts. Additionally, the establishment of steamship navigation and marketing enticements (advance labor contracts, mayloun or pre-paid tickets, etc.) by shipping companies from the late 1870s onwards greatly eased travel and attracted migrants. But it was the word of mouth of the first emigrants that drew more and more to leave their homes and board ships sailing to the Americas. In letters or during their visits, these early immigrants told of golden opportunities abroad (and hardships as well), and actively invited others (family and friends) to join them across the ocean. Finally, WWI and the accompanying terrible famine, which killed nearly one-third of the population in Mount Lebanon alone, spurred another smaller wave of immigration from the Levant after 1919 which lasted through 1924 when the Johnson-Reed Act severely restricted immigration of any non-white Europeans. Because of all this, textile workers from Homs, merchants from Bethlehem, peasants from Mount Lebanon, and teachers from Beirut and Damascus boarded steamboats in the city of Beirut and headed for “Amirka,” North and South.

While it is clear that a desire for a better economic life was a major factor driving thousands to leave the Eastern Mediterranean, each immigrant story remains unique in its combination of factors and elements that compelled the journey of individuals.

[1] The first 19th century Arab to arrive in the US was Antonios Bishallany who came to the US in 1854

[2] An estimated 120,000 went to the US and another estimated 210,000 made their way to South America, mainly Argentina and Brazil. However, these numbers are rough estimates that are difficult to ascertain because of the circular pattern of population movement. For example, between 1887 and 1913, about 131,000 immigrants left Lebanon for Argentina, but some 83,000 traveled back to Lebanon in that same time period (Harfoush, 49). Between 1899 and 1910, and based on Ellis Island immigration records, some 90,000 immigrants left Mount Lebanon for the United States. This does not take into account the previous 10 years, nor are we certain how many returned. By the census of 1930 it seems that only 56,389 of the 147,171 Arab-Americans were born in the Eastern Mediterranean, with the remaining population being American-born.

[3] Erik-Jan Zürcher, “The Ottoman Conscription System In Theory And Practice, 1844-1918”, International Review of Social History 43 (3) (1998), pp. 437-449.

[4] Mikhail As’ad Rustum, Kitab al-Ghareeb fil-Gharb, p. 17 (Philadelphia, al-Matba’a al-Sharqiyya: 1895)

[5] Salim Hassan Hashi, Yawmiyat Lubnani fi Ayyam al-Mutasarrifiyya (Diaries of a Lebanese During the Period of Mutasarrifiyya), p. 57

[6]Interview with Michael Haddy, Naff Arab-American Collection, Smithsonian Museum

- Categories: