The Early Lebanese in America: A Demographic Portrait, 1880-1930

This post was written by Dr. Akram Khater, Director of the Khayrallah Center, and Marjorie Stevens, Senior Researcher. It is the third installment in the center’s Core Story, a series of essays detailing the broader history of Lebanese immigration to the United States. Some material for this essay was based on a previous demographic analysis conducted by the center in 2015 co-authored by sociologist, Peter Knepper.

Introduction

Between 1880 and 1930 tens of thousands of immigrants left the Eastern Mediterranean and traveled to the United States. While this much is certain, until now we have not had a clear and detailed demographic portrait of these early immigrants.

At best we have imprecise, and quite often erroneous, answers to questions such as: how many immigrants were living in the United States between 1900 and 1930? Where did they live? How many of them were women? How many were married, single or divorced? How many children did they have, if any? What was their average age? What kind of work did they do?

The problem has been that most information compiled by researchers was based on rough estimates that, more often than not, provided wildly divergent numbers leaving one more perplexed than informed.

Recognizing this pressing need, the Khayrallah Center launched an ongoing project to provide reliable population data for first-wave Lebanese-Americans from 1900 to 1930. We mined decennial US Census data from 1900 to 1930, as well as other data sets to create a comprehensive profile of the earliest Lebanese-Americans. Below are some of these questions and the best answers we can provide at this point with any factual accuracy. Together, they give us the first clear demographic portrait of the earliest Lebanese immigrants to the United States.

How Many Came to America?

We do not know for sure, but we can finally provide the best estimate. There are three main sources for counting how many Levantine¹ immigrants came:

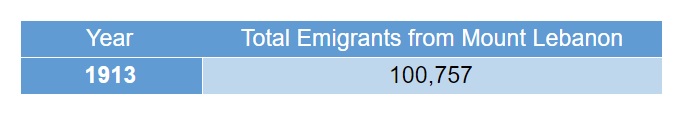

1913 Ottoman Census: this source provides the most granular data, counting those who emigrated from each village and district in Mount Lebanon. However, this census only represents one Ottoman province from which the early wave of “Syrians” came, ignoring other areas like Damascus, Hama, Aleppo, and Bethlehem. It also records all of those who left regardless of whether they were destined for Brazil, Australia, or the United States.

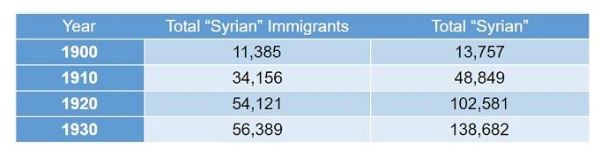

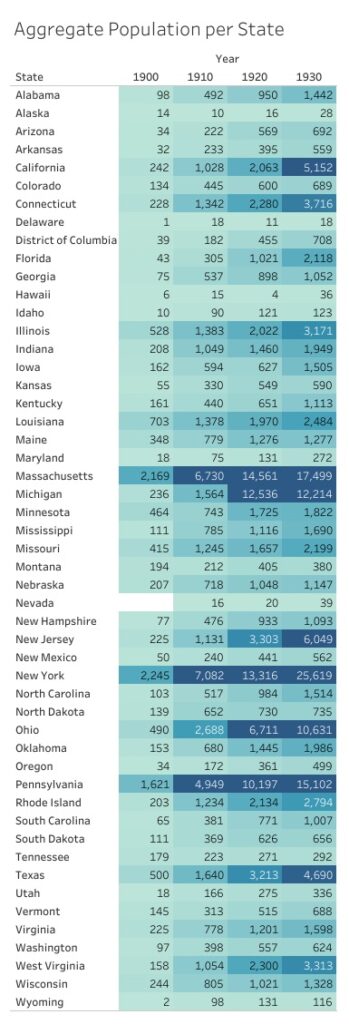

1900-1930 United States Federal Censuses: theses censuses, taken every ten years record US residents who claimed “Syria,” “Palestine,” or “Turkey” as their place of birth. Though fairly extant, they are limited in that census takers may not have been thorough, may have mis-recorded data, or may have chosen to artificially under-count particular groups. The chart below shows the total population of “Syrian” immigrants in the United States according to the US Census as well as the total ethnic “Syrian” population (including children born to “Syrian” immigrants in the United States).

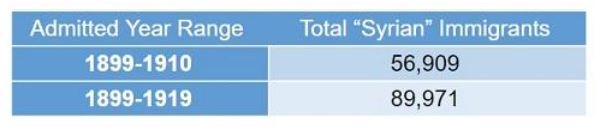

1911 and 1919 Reports of the US Immigration Commission: Each year, the Commissioner General of Immigration tabulated data on American immigrants. In 1911 and 1919, a congressional committee compiled reports, ultimately aimed at gathering data to help draft legislation. The reports quantified data about immigrants including country of origin, race, gender, age, literacy, occupation, finances, and more. However, the immigration reports were compiled with specific partisan agendas in mind, and were directly used to instate literacy tests and country of origin quotas that all but eliminated immigration from everywhere except Northwest Europe in the 1920s. Thus, the data they provide might be biased against certain groups, including those from the Ottoman Empire and categorized as “Syrian.”

Aside from biases in the source, the Immigration Commission reports also do not fully account for transmigration, or immigrants who temporarily or permanently returned to Lebanon. Likewise, they do not account for immigrants who entered the country multiple times (for example, to escort family members to the US). In 1908 and 1909, the reports did provide data on these points, indicating that in those years, about 25% of immigrants returned. This suggests that overall numbers for the migration period from immigration records may be inflated by that amount.

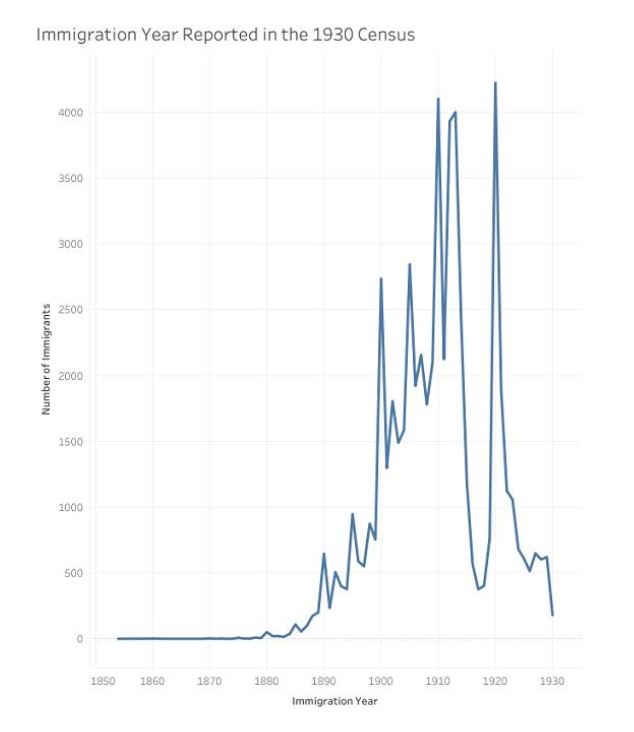

These three sources agree that the majority of Lebanese immigrants came here between 1890 and 1920, with an interruption during World War I, when the French and British enforced a severe sea blockade off the coast of Lebanon. There was another short-lived spike in immigration between 1920 and 1923. Then, in 1924 the passage of restrictive immigration laws in the US effectively reduced that first wave to a trickle.

What is evident from these numbers is that the widely held idea that around 120,000 Lebanese immigrated to the US is incorrect. Rather, the census places the number closer to 60,000, with the rest being children born in the US.

Gender

Census data also provide a closer look at the gender and age of early Lebanese immigrants. While we tend to think of these pioneers are predominantly male, what becomes quickly clear from the recorded numbers is that women were ever present in this migratory movement.

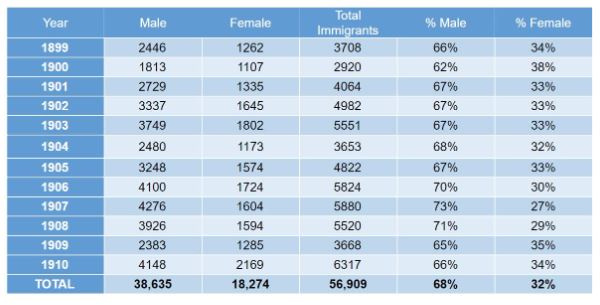

The 1911 Reports of the Immigration Commission indicate that the gender ratio of “Syrians” arriving in the United States was about two men for every woman:

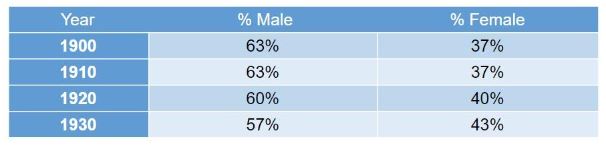

The US census provides similar ratios, but shows an increasing percentage of women by 1920, reflecting the later arrival of women, especially after the end of blockade that ruptured families during World War I.

Age Distribution

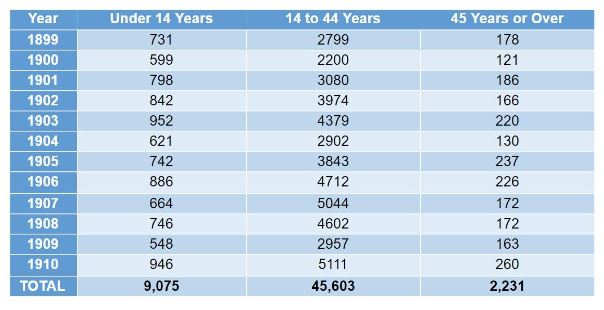

Since most Lebanese immigrants came to the United States (and other destinations) to work and then return home to live a more secure and comfortable life, then it is not surprising that the majority were of working age. The chart below shows the age of “Syrian” immigrants according to the 1911 Reports of the Immigration Commission.

Literacy and Occupation

Immigrants who came to the US between 1880 and 1930 were for the most part illiterate. The 1911 Reports noted that of the 47,834 Lebanese arriving in the US between 1899 and 1910, and who were 14 years or older, 53.3% (or 25,496) were illiterate in their own language. In comparison, the same report provided that only 1.6% of the “native white” population of the US was illiterate, while illiteracy among the foreign born population in this same time period was only 12.6%. (Najib Arbeely, one of the earliest immigrants to the US and a highly educated doctor, was the inspector at Ellis Island charged with conducting the tests on arriving immigrants). While this provides interesting comparative data which may be accurate, it is important to keep in mind that Immigration Commission chair Senator Dillingham was himself instrumental in instating the literacy test as a means of halting immigration from places like Syria. Thus, it may very well be that these reports are not accurate, and reflect more of the racial biases against non-Europeans than the real level of literacy among these early Arabic-speaking immigrants.

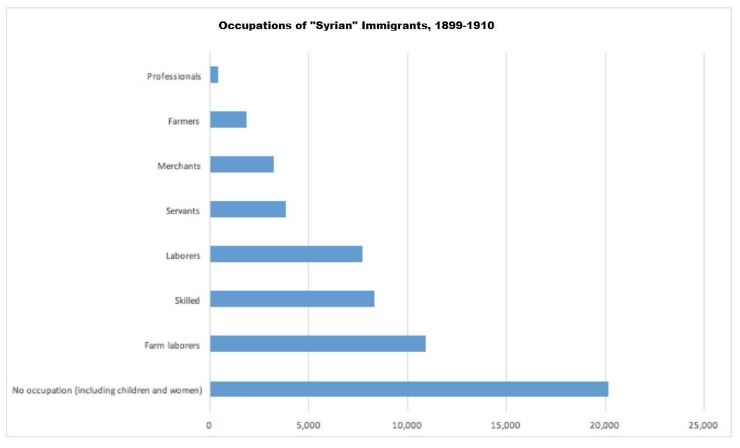

The types of occupations recorded upon immigration shed some light on the lack of literacy in this immigrant group. As the chart below shows, only a small portion of occupations (merchants, professionals, and a portion of skilled workers) would imply the need or possession of literacy. The great majority noted that they were either peasants/farmers, domestic servants, or unskilled workers.

Read a complete breakdown of reported occupations for “Syrian” immigrants arriving between 1899 and 1910 here.

Where Did They Go?

As with most early 20th century immigrants to the US, these early Arabic speakers arrived mainly at Ellis Island, “where the odours of disinfectants are worse than the stench of steerage, they await behind the bars their turn… uttering such whimpers of expectancy, exchanging such gestures of hope.” For many others their route was far more circuitous. Some had initially traveled on purpose or by chance to other parts of the Americas stretching from Brazil to Mexico. Others (around 4,600 or 10% of the total number seeking entry to the US between 1899 and 1907) were turned away from Ellis Island because of “loathsome and contagious disease” (predominantly Trachoma) or insufficient funds to permit their entry. They would then travel to Cuba, the Caribbean or Mexico to live and work with relatives until they could make their way back through the ports of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, Philadelphia, or overland across the Mexican or Canadian borders.

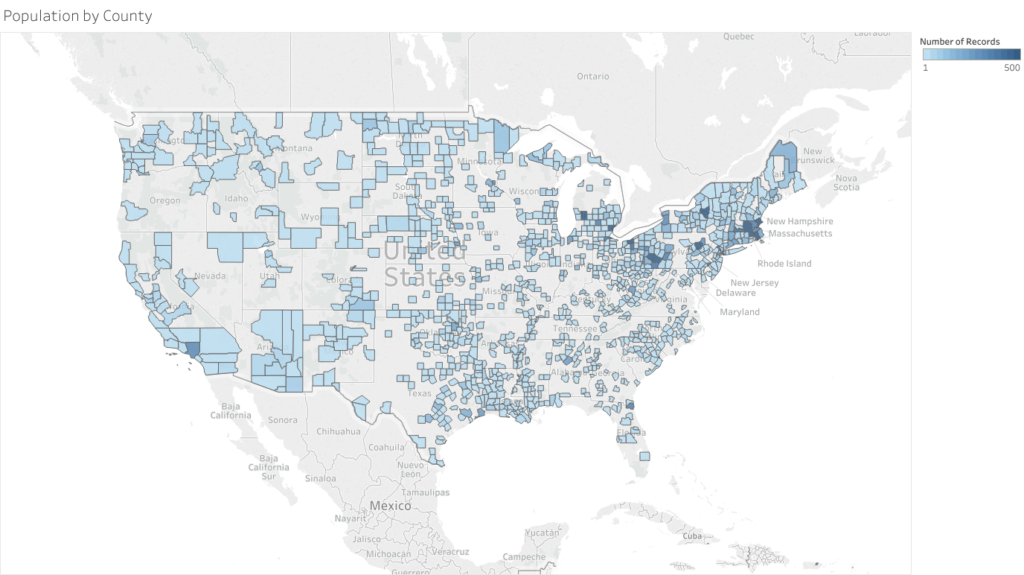

Irrespective of how they entered the U.S., immigrants quickly spread throughout the country. Many headed immediately to the rural American frontiers to peddle, like Annie Abdo who settled in Oklahoma in the 1880s ultimately investing in real estate during the state’s land rush. Others, especially around the turn of the 20th century, sought industrial jobs in New England and Michigan factories. By 1910, around 3,000 Lebanese lived in Lawrence, Massachusetts and worked in the city’s textile mills. Immigrants crisscrossed the country between Florida and Alaska, also moving to the American South in larger proportions than other immigrant groups of the time period.² Within ten years of the start of mass immigration, Arab Americans were found in every state, and by 1920 they were living and working in over 80% of U.S. counties.

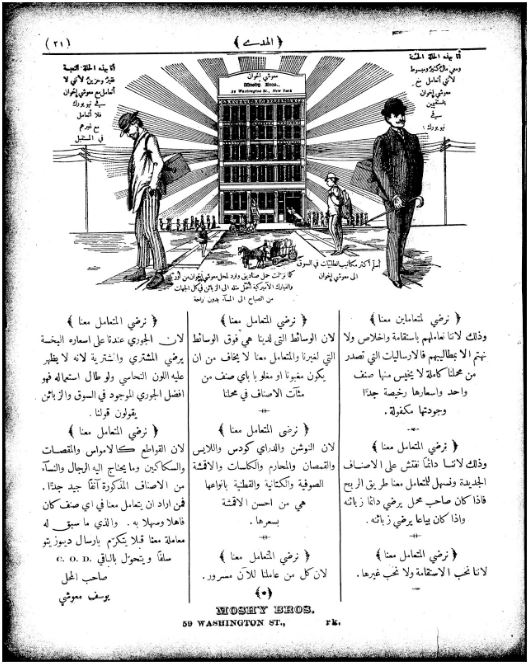

This unusually widespread settlement was driven by the search for work and quick fortunes that could facilitate their return home. At one point or another, but especially in the earliest years of immigration as many as 40% of those working, peddled. This line of work prompted them to embark on America’s backroads and leave behind their ethnic community enclaves. This pattern was part of an immigrant hub-spokes system of trade that developed over time. Cities and towns such as New York, or Fort Wayne, Indiana became distribution nodes where well established Lebanese merchants would supply relatives, friends from the village, or any other newcomer, with merchandise such as thread, shaving blades, and lace, and send them along the railroad lines to farther and farther places to be itinerant peddlers. For example, H. J. Kassem of Rockwood, Tennessee, regularly wired funds to new arrivals in Ellis Island to enlist them in his venture wherein he sent dozens of “peddlers into the mountain districts [and] manages to keep bank account well up in the four figure column.”³ In July of 1904, two peddlers, Ali Salaman Qabul and Mahmud Hamzy, were at the train station in Hamilton, Ohio, waiting to take delivery of a shipment of “notions” sent to them from Fort Wayne, Indiana (some 140 miles away) by Khalil “Kobal” Farah. After picking up the shipment, they traveled a route that normally took them to Princeton, Monroe, Mason, Lebanon and then as far as Wilmington, Ohio. Many ranged even farther. Dr. Michael Shadid saved enough money to attend the University of Washington medical school, by peddling his way from New York to Texas selling jewelry.

But the demographic map provides even more insights. For instance, Texas consistently shows high numbers of Lebanese. In 1910 it had the fourth highest population after New York, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts. This may be a result of overflow of immigrants who originally settled in South and Central America but decided to relocate to the United States via the Mexican border. Or it could be due to the fact that those immigrants who were denied entry through the main port of Ellis Island–due to communicable diseases like trachoma, being considered paupers if they had less than $25 in their possession, or for lack of a sponsor American or Lebanese–managed to enter the US more easily through Mexico.

Beyond Texas, and in general, this new data shows that the South was demographically more prominent than existing histories of Lebanese migration would lead one to believe. For instance, in 1920, 20% of Lebanese immigrants lived in the South and from 1900 to 1930 that region never accounts for less than 10% of the population. This revelation necessitates a re-telling of the stories of Lebanese immigration to the US, and a shift from an over-emphasis on the northeast.

Moreover, examining the population by county gives a more precise picture of population distribution. While one Western state may count far fewer immigrants than its northeastern counterpart, a particular Western county may still have a significant population that rivals counties in densely populated states. For example, between 1900 and 1930, Las Animas County, in Colorado, reported hundreds of immigrants living in this remote–and by some measures unlikely–corner of the state. Aside from showing that Lebanese immigrants were spread throughout the US, this “peculiarity” reinforces our earlier conclusion that we cannot presume that the history and lives of Lebanese immigrants was centered in New England or New York and Pennsylvania. This data begs us to cast a wider look and ask new questions, such as what led hundreds of immigrants to a clearly isolated community in the West? Perhaps servicing mining operations and miners might be the answer in this particular case.

As important as it is to note counties with high populations, we have to give serious consideration to counties with a single or very few immigrants, a phenomenon seen most commonly in 1900 and 1910 censuses. Two such men were Albert Razook and John Mansoor, dry goods peddlers who accounted for the only Lebanese in their respective counties of Sumner and Marion, Kansas in 1900. Razook, age 22 had been in the country five years and lived in an American household. John Mansoor, a 42 year old immigrant of three years was living with a Russian family despite having his own wife and children elsewhere. This solitary life compels us to consider whether these immigrants in far-flung countries–many of whom spoke little English–experienced a lonely existence isolated from people familiar with their language and culture. Or perhaps they sought such a life precisely because it took them far away from the densely populated centers in New York or Dearborn.

Conclusion

Many questions remain about the demographic makeup of the early Lebanese immigrant communities in the US. However, research at the Khayrallah Center is bringing us ever closer to more definitive answers. For example, the preliminary results presented in this essay provide a major revision to our understanding of this community.

- The number of immigrants coming to the US from “Syria,” is demonstrably lower than previously assumed or calculated by researchers. Rather than the 120,000 figure usually given, we now know that in total around 60,000 Syrians (or half as many as had been assumed) immigrated to the US. However, when including the total ethnic population (i.e. incorporating the children of immigrants) in this assessment, a figure of nearly 140,000 is reached by 1930.

- As some scholars have argued contrary to long held preconceived notions, the data here shows that women were ever present as immigrants, even from the earliest days of “Syrian” immigration, and in at least 15% of the cases were heads of households. This gives them a far bigger role in the process of immigration, and settlement across the US.

- Although earlier histories of “Syrian” immigration to the US focus almost exclusively on the Northeast region, our mapping of the census data shows that “Syrians” were not confined to that area. Rather, they lived across the length and breadth of the country. This early and sustained widespread dispersal led to regional variations in terms of the types of work they pursued, their relationship to the larger community, adherence to their original faith or conversion to new ones, and many other aspects of their lives. In other words, we can longer speak of a single narrative of “Syrian” immigration, but have to contend with multiple ones that diverge as much as they have common themes.

Notes

- We will use the term Levantine, Eastern Mediterranean, “Syrian” and Lebanese interchangeably to indicate the people who came to the United States from the area that is today covered by Lebanon, Syria, Palestine/Israel.

- Arab Americans diverged significantly from the dispersal pattern of most other immigrant communities. For example, Chinese and Japanese immigrants were concentrated on the West Coast both by design (farming) and by anti-Asian laws that date back to the 1880s; Mexican immigrants lived and worked primarily in the American Southwest in mines and fields; and Polish immigrants lived in the northeastern quadrant of the U.S. stretching from the Midwest to the Northeast.

- The Tennessean, June 22, 1907, p. 2.

- Categories: