Tarzan in Arabic

“Who is Tarzan?” Salloum Mokarzel (1881–1952) asked this question in his November 18, 1932, editorial in Al-Hoda. He wrote it as an introduction to, and in anticipation of, the debut of the Arabic-translated Tarzan of the Apes comic strip that was to appear in al-Hoda over the next thirteen years. In an effort to appeal to his audience, Salloum tried to situate Edgar Rice Burroughs’s (1875–1950) white, male supremacist, colonial adventure tale in the context of familiar Arabic folklore legends, thereby paving the way for a new (and notably white) hero for the newspaper’s “‘Syrian” migrant readership to embrace.

Salloum wrote his editorial during the US interwar period, a time marked by intensifying anti-immigrant feelings and violence. The fragile, grudging acceptance of Syrians and their “whiteness,” which had been determined in a series of naturalization test cases tried in US courts, faced increasing contestestation in quotidian life. In this climate, Salloum and his brother Naoum Mokarzel (1864–1932), who both emigrated from the village of Freikah in Mount Lebanon, became leaders in the genesis and development of the Syrian-American press published in Arabic and English. The Mokarzels used their publications to promote the compatibility of Syrians with “White” American society and values, as well as to build nodes of connection and convergence of US and homeland cultures within the Syrian migrant community.

In 1898, Naoum founded the newspaper Al-Hoda (The Guidance) which became the most widely read and longest-running Arabic news publication in the United States (1898–1972). Salloum, the younger brother, founded The Syrian World (1926–1931), an English-language newspaper oriented toward second-generation Syrian migrants living in the United States. Using their stature as journalistic powerhouses and respected members of the Syrian Mahjar community, the Mokarzels promoted their political aims, which included campaigning for the future of an independent Lebanon (with support from France). In addition, they worked assiduously to ensure the integration of Syrians into the United States, whom the Mokarzels claimed were descendents of the storied ancient Phoenician traders and thus “natural” and worthy members of “white” America, and peddlers of its capitalist economy.

Salloum assumed leadership of Al-Hoda in 1932 after Naoum’s death in April of that year. After leaving The Syrian World and returning to writing predominately in Arabic, Salloum continued to orient his content towards Syrians who were grappling with how to make sense of Syrian and American cultures. Salloum’s intent to shape his Syrian brothers and sisters into Americanized incarnations of their Phoenician ancestors took one form in the translation of Tarzan, America’s “original superhero,” into Modern Standard Arabic.

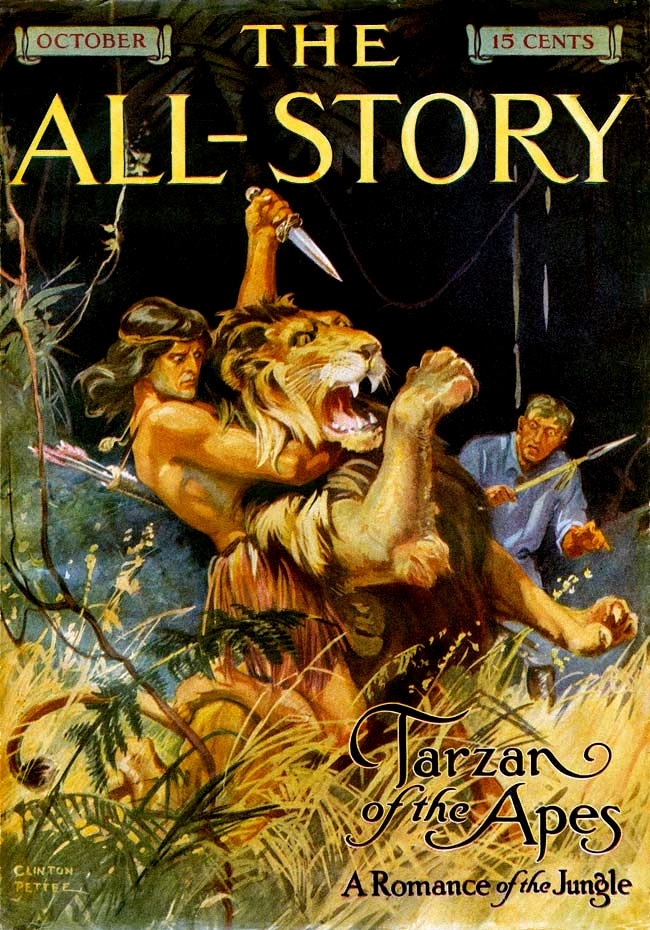

Returning to the question, “Who is Tarzan?” Salloum did not answer by expounding on Tarzan’s soaring critical acclaim and platform expansion from serialized novel, first published in All-Story Magazine in 1912, to the 1932 Hollywood blockbuster starring Olympian Johnny Weissmuller. Rather, Mokarzel stitched the heroic poster boy of eugenics, empire, colonialism, and white supremacy into a quilt of familiar Arab folklore heroes. By connecting peak US pop culture to traditional Arabic storytelling, Salloum rendered Tarzan legible to the Arabic-speaking Syrian readership.

Salloum reified classic binaries–East vs. West, antiquity vs. modernity–in comparing American stories with Arabic legends. Salloum writes, “Not the strength of ‘Antar, the courage of Jadar, the adventures of Sinbad, nor the voices of the ancient bold Arab heroes. . . is greater than what you will read about the heroism of Tarzan.” In a not-so-subtle nod to the primacy of US culture, Tarzan, the epitome of white masculinity, beats out all ancient Arab heroes with his unrivaled nature. For Salloum, the “King of the Apes” functioned as the new and improved role model for Syrian-American modern men and women. He describes him to his readers as follows: “Tarzan is the king of beasts and forests, Tarzan is the son of nature and instinct, Tarzan is the handsome lover, Tarzan is the mighty and brave man, Tarzan is the conqueror of enemies and champion of the weak.”

For at least the next thirteen years (according to available digitized issues of Al-Hoda) Tarzan featured daily in the newspaper, save for breaks between new seasons of the series. As shared in the first few comic strips published in Al-Hoda, Tarzan’s story begins with the deaths of his parents, Lord and Lady Greystoke, who were British agents sent to oversee a West African colony. A group of apes soon adopt the orphan, raise him as their own, and rename him “Tarzan,” meaning “white skin.” His supposed “natural” abilities and intellect enable him to rise to the status of a revered leader, exerting power and dominance over the landscape and wildlife, and marking him as superior to the indigenous black peoples of the African continent. The succeeding series builds off this origin story and follows his exploits in the jungle and beyond, as Tarzan wrestles lions and kills “cannibals” amidst other adventures. Regardless of the challenges faced by Tarzan, Burroughs leaves no room for doubt that Tarzan’s “whiteness” underlies all his success and dominion in the jungle.

So, why did Salloum decide to feature this blatantly racist and supremacist comic strip in Al-Hoda? Why did the newspaper think its readership would enjoy reading about the exploits of a singular white man dominating the African landscapes and peoples? What values or characteristics of Tarzan did Al-Hoda editors find compelling for their readers? By extension, what does this long-standing commitment to publishing the comic strip suggest about the Mokarzels’ racial and political views?

In the weeks to come, we will explore some of the implications of Tarzan’s thirteen-year run in Al-Hoda. Delving into topics of race, gender, and power, we will examine what the enduring popularity of Tarzan, a narrative at the intersection of pop culture fantasy and the pseudoscience of eugenics and racial superiority, reveals about Syrian diasporic politics, racial ideologies, and gender conception in the first half of the twentieth-century United States.

This post was written by Lily Glaser, an undergraduate student at Barnard College who interned with the Khayrallah Center in summer 2024.

- Categories: