Phoenician or Arab, Lebanese or Syrian ~ Who were the early Immigrants to America?

This article is authored by Dr. Akram Khater, Director of the Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies and Khayrallah Distinguished Professor of Lebanese Diaspora Studies, and Professor of History at NC State. His earlier article focused on Lebanese-Americans in WWI.

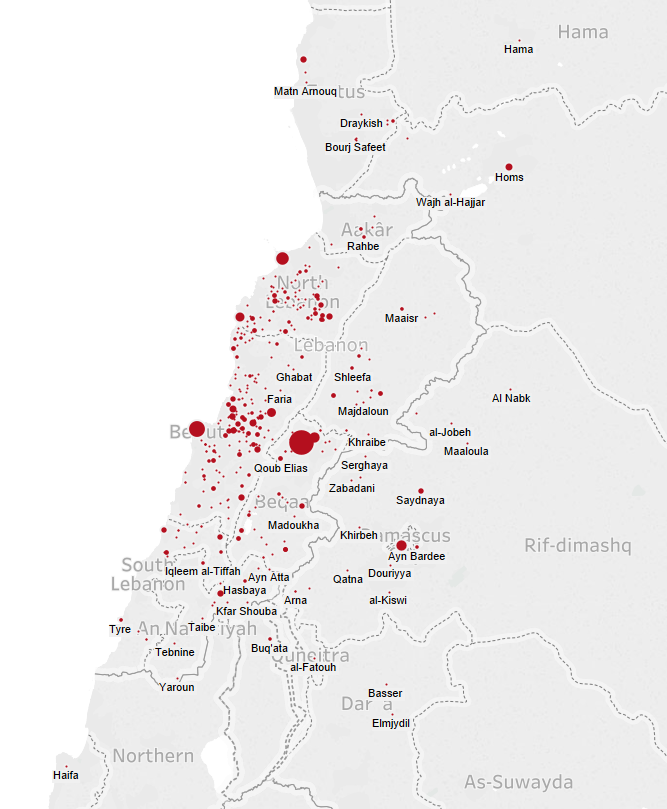

Between the 1870s and the 1930s some 120,000 immigrants left the Eastern Mediterranean and traveled to the U.S., with another 220,000 departing for Central and South America and landing in destinations like Argentina and Brazil. These men, women and children, peasants and tradesmen, factory workers, teachers and merchants came from across “Greater Syria,” an Ottoman province that today encompasses Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine/Israel. We do not know for certain their religious distribution but they included Antiochian Orthodox, Druzes, Jews, Maronite Catholics, Sunni and Shi’a Muslims.

Their sense of self was located within villages and towns like Homs, Bayt Meri, Bethlehem, or Rashaya, and distilled through their experiences of family and religion. Ethnicity and nationality were meaningless to the great majority of them. In other words, when they left they were neither Lebanese nor Syrian, Phoenician nor Arab. However, their sojourns into the racially charged American social, legal and political landscape forced them to re-define themselves in terms of ethnic and national identity. Moreover, World War I and the subsequent division of their homelands into nations under the tutelage of French colonial power, engaged them in spirited—and sometimes violent—debates about who they were and where they came from. The result of these various forces differed but overlapped, and changed identities that were more fluid than fixed, and easier to use as labels than to substantially define.

As these immigrants traveled across the Mediterranean and Atlantic to “Amirka” they were required to have an ethnic/national identity if they were to gain entry to the place that they hoped would make them a handsome sum of money and afford them new opportunities. Ship companies’ clerks and Ellis Island inspectors were not interested in the intimate world of small villages like ‘Ayn Ibl (in South Lebanon), or even the geographically distinct and rapidly growing city of Beirut. Rather, until 1899 these company employees and state functionaries jotted down “Turkey in Asia” in their registers next to the migrant’s name, and after 1900 replaced it with “Syria” for most entries while keeping the earlier term in some cases. Thus, upon entrance into the US, immigrants acquired a different and larger identity—“Syrian”—than the ones they had left with. The label “Syria” made sense geographically as a designation for where they came from, but it also represented an emerging political project and idea among the educated urban elites of their homelands.

“Syria”—as a distinct political and cultural space—was first popularized during the 19th century by Jesuit missionaries in Mount Lebanon who established transformative educational establishments like the Oriental Seminary in the village of Ghazir, or the Université Saint Joseph in Beirut (founded in 1875). Starting in the 1880s their faculty, including intellectual luminaries like Henri Lammens and Louis Cheikho, undertook decades-long project to “resurrect” and write the history of “Syria”—with the district of Mount Lebanon as its religious, cultural and administrative heart—as a separate Christian entity radically different from the surrounding and predominantly Muslim Ottoman provinces. Lammens popularized the idea of Mount Lebanon as a refuge for oppressed Christian minorities in his iconic book La Syrie: Prècis Historique (Syria: A Historical Summary).

By 1908 these intellectuals, along with the Maronite church and its elites, French travelers and officials went one step further where they imagined the Maronites to be the “Français du Levant,” (The French of the Levant): a culturally distinct and European group who deserve their own entity in an expanded Mount Lebanon. This was perhaps best captured by Youssef al-Souda, a Lebanese émigré in Egypt—educated at the Université Saint Joseph between 1900 and 1907. In his book Fi Sabil Lubnan (For the Sake of Lebanon) which he published in 1919 he noted: “ Every nation has a strong desire to return to its roots…so is Lebanon proud to remember and remind all that it is the cradle of civilization in the world. It was born on the slopes of its mountain and ripened on its shores, and from there the Phoenicians carried it to the four corners of the earth.” (Asher Kaufman, Reviving Phoenicia, p. 48)

Similarly, the Syrian Protestant College (a higher education institution established in 1866 in Beirut by American Presbyterians, and later renamed the American University of Beirut), played a critical role in giving substance to the idea of “Syria” as a distinct cultural and political region in the Middle East. Its American professors and more importantly local graduates were central to the Nahda—or the Arab renaissance movement of the 19th century—which used Arabic “as a vehicle for the formation of a secular identity in the territory they defined as geographical Syria.” (Asher Kaufman, Reviving Phoenicia, p. 39). However, unlike the Jesuit missionaries and their students, the emphasis by this cohort of intellectuals was not on a Catholic/Christian nation, but rather on an ecumenical and secular Syria.

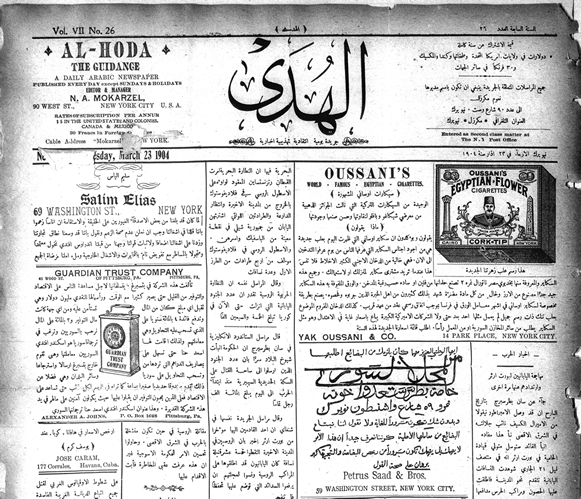

Thus, by the dawn of the 20th century, when the majority of Levantine immigrants arrived in the US, “Syrian” as an ethnic and national origin was reasonable enough to accept even if they were not quite sure what it meant. As community organizations and publications proliferated and gave ethnic substance to these migratory individuals and families, the term “Syrian” became more common. The center of the immigrant population in New York came to be known as the “Syrian Colony.” In letters sent back to the Maronite Patriarch Elias al-Howayek between 1899 and 1931, members of the diasporic communities regularly referred to themselves as “Syrians.” For example, in 1901 Mikhail Daher Abou Sleyman wrote asking to remove the local Maronite priest who was “bigoted” because “most of the Syrians in New York are cultured…and hate bigotry.” Community newspapers also adopted this term in their articles and advertisements. For instance, an ad in Kawkab Amirka (The Planet of America) by the Compagnie Generale Trans-Atlantique promised “Our Syrian Voyagers” comfort and security in their journey back to “Syria.” Others, like The Syrian World, adopted the name in their very identity. Even the Federal government of the U.S. adopted this term to identify immigrants from the Eastern Mediterranean. In 1911 the Immigration Commission of the House published a Dictionary of Races or Peoples wherein the “Syrian” was identified as a native Aramaic “race” of Syria and distinct from Arabs. While both spoke Arabic and were Semites, and many Arabs lived in Syria, the “Syrians” were defined as predominantly Christian and were descendants of the Phoenicians.

Two key Maronite intellectuals amongst the early immigrants to America concurred on this distinction but disagreed with each other on its meaning. Naoum Mokarzel (publisher of al-Hoda) and Philip Khuri Hitti (professor of Middle East studies at Princeton) both arrived in the U.S. just as the “Immigration problem” was being debated in the U.S., and where attempts to limit immigration to “Caucasians” was gaining steam. Mokarzel used al-Hoda as a platform to proclaim that the “Syrians” were part of the white race different from Arabs and Turks, and thus not subject to these emerging restrictions. (This is an argument that was carried into the courts to defend the rights of “Syrians” to become US citizens). He argued, like Hitti, that their Phoenician roots made them part of European culture. Hitti wrote explicitly of this in his book The Syrians in America where he noted: “With this [Phoenician-Canaanite] Semitic stock as a substratum the Syrians are a highly mixed race of whom some rightly trace their origin back to the Greek settlers and colonists…others to the Frankish and other European Crusaders…” (Asher Kaufman, Reviving Phoenicia, p. 77) Yet, while Hitti remained dedicated to the idea of Lebanon as part of a larger Syria, Mokarzel slowly moved toward a “Lebanist” position by World War I. He argued, along with the Lebanese League of Revival (based in Alexandria, Egypt) that Lebanon was distinct from the rest of the area in its non-Arab identity. Acting on this belief, he traveled after World War I to the Peace Conference in Versailles (France) to agitate for an independent Lebanon. On September 1, 1920 this project came to fruition when the French colonial authorities—at the behest of the Maronite church and intellectuals, and to satisfy its own imperial interests—created Le Grand Liban (Greater Lebanon). The newly created nation-state began to formally recognize Levantine immigrants in the U.S. and beyond as Lebanese citizens. Similarly, the French colonial authorities came to count and regard these immigrants as citizens of Lebanon.

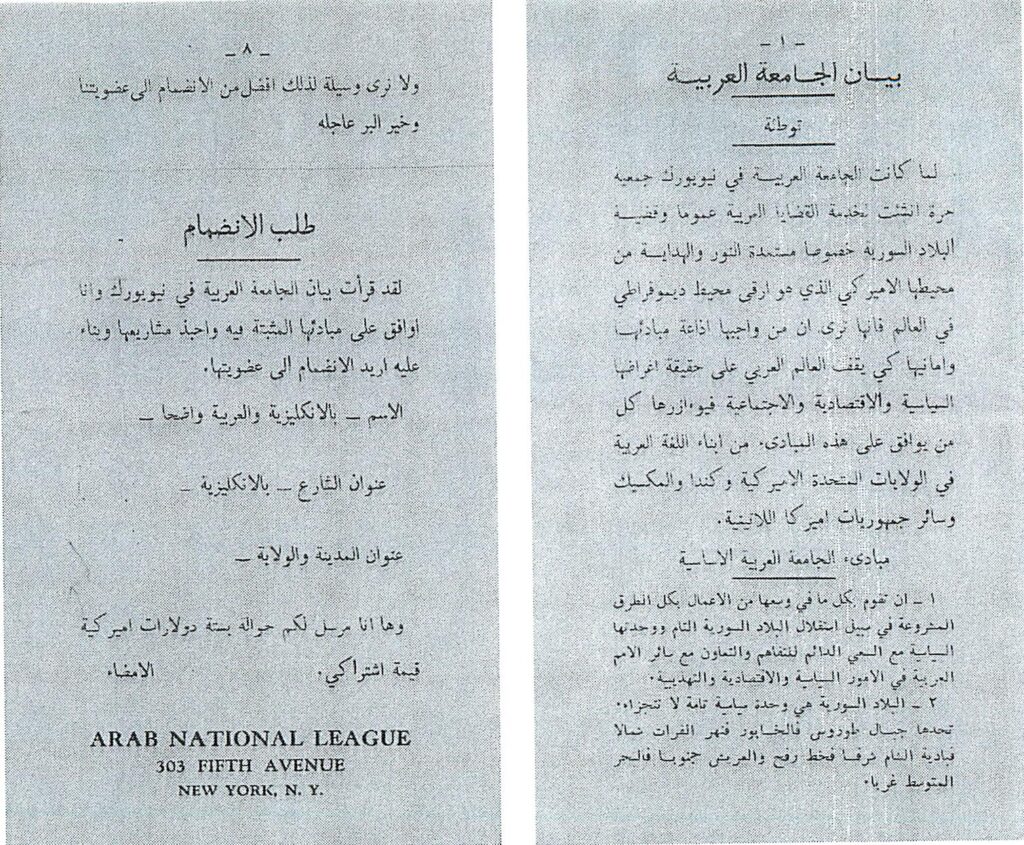

Other members of the Levantine community were not so wedded to the idea of a separate Lebanon or one that abandoned its Arab heritage. In 1925 the “Syrian Revolt” broke out in the Syrian hinterlands against French colonial power. Hailed as the “Druze Revolt” by the Druze and Muslim members of the Detroit Syrian Community, the revolt galvanized them to create the New Syria Party (NSP) which declared its support for an Arab Syria. The leader of the NSP, a Muslim preacher by the name of Kalil Bazzy invited one of the top leaders of the revolt, Shakib Arslan, to visit Detroit and deliver a talk about the revolt. This move alienated the Maronite Christian community there (but not the Antiochian Orthodox one), who believed that Arslan was responsible for the reported massacres of Christians in South Lebanon, and more importantly because he represented a vision of a non-Christian dominated “Syria.” A journalist for the Detroit Free Press described the situation as follows: “In such a time [1926] the Detroit Syrian colony seems really like a “Little Syria” for here, on a smaller scale, appear the same divisions of partisan thought and factional sympathy.” (Sally Howell, Old Islam in Detroit, p. 87). Hani Bawardi carries this further by writing about the development of an Arab political consciousness in the 1930s especially with the establishment of the Arab National League which dedicated itself to rendering “political, cultural, educational and economic service to the Arab countries.” While certainly many members of the community remained aloof, the existence and persistence of this organization as an “Arab” diasporic entity is quite removed from the distinction that Mokarzel and Hitti stipulated between “Syrian,” “Lebanese” and “Arab.” (Ameen Rihani delivered an impassioned speech in 1937 about Palestine that you can listen to here.)

Debates about the identity of these Eastern Mediterranean immigrants continued after the 1930s and remain a point of contention within the Lebanese and Arab community today. Their persistence and changes over time are a warning against the hazards of assigning a single fixed identity to all those immigrants who came from “Greater Syria.” Rather, different groups adopted varying identities with some opting for being Christian-Lebanese, while others adopted a more secular “Syrian” label, and still others saw themselves as part of a larger Arab world. But even these were never set positions as later generations—facing different political circumstances than their forbearers driven by the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, U.S. military involvement in the Middle East, and the rise of Islamist politics—changed how they saw and represented themselves in “Amirka.”

- Categories: