Questioning Assumptions: Gender & Lebanese Immigration

This post is written by Dr. Akram Khater, Director of the Khayrallah Center, and Marjorie Stevens, Senior Researcher at the Khayrallah Center. For similar posts, check out migration and health, and Lebanese in the US Census.

At the entrance to the Port of Beirut there stands a statue of a man in 19th century village attire, looking out to the seas. In Arabic it is titled “The Lebanese [Male] Emigrant: From Lebanon to the World.” It was erected in 2003–with a duplicate unveiled earlier in Mexico and another one later in Australia–to commemorate the departure of hundreds of thousands of emigrants from the shores of Lebanon to the Americas, Africa and Australia. In frozen bronze, the statue embodies the established tale of Lebanese immigration to the US (among other places) of single men who ventured from their villages, some alone and many in small groups. On arrival in the US they peddled until they earned enough money to open stores, send for their families or brides, and continue their way up the proverbial ladder to a middle class life.

Yet, recent research indicates that Lebanese immigration to the US challenges this over-simplified story. We have found that women immigrated in larger numbers than previously thought and they did so for diverse and myriad reasons that go beyond simply family reunification. Broken marriages and mothers leaving their children don’t fit into the romanticized perception of the immigrant woman and family. Yet, immigrants’ lives in the early 1900s were as complicated as our lives today. Certainly many came as part of their family’s migration. However, some marriages were abusive or indifferent. Some women sought autonomy and careers of their own and left for America while many left their husbands and children because it was the most practical economic decision for their family.

Researchers at the Khayrallah Center have used data from the US Federal Census to examine and question previous assumptions about women in Lebanese immigrant society from 1900 to 1930.

Did women immigrate later than men?

Answer: Not really.

We don’t have census data for 1890 (which burned in a fire), but from 1900 to 1910, 62 percent of Lebanese immigrants in the US were men and 38 percent were women. Contrary to the idea that men came first and women followed, this suggests that men and women immigrated at steady rates during this foundational period, though fewer women immigrated overall. By 1920, women’s share increased to 40 percent and by 1930 it rose to 43 percent or almost half. An increase in female immigration after World War I (1918) and before quotas stifled immigration to the US in the 1920s caused this spike. Between 1914 and 1919, one out of every three Lebanese tragically died due to war and famine. Lebanon lost more men than women due to the forced conscription of adult men into the Ottoman army (infamously known as safar barlik ) and their demise at the front. This left many women in incredibly vulnerable situations, suffering from lack of food and security and desperate to survive. Thus, many left Lebanon during and shortly after the war seeking their salvation and that of their children. As a result, the number of Lebanese women entering the US surpassed the number of immigrating men for the first time.

Was the ratio of men to women different in different parts of the US?

Answer: Yes.

We divided the US into four regions–Northeast, Midwest, South, and West–and examined how the breakup of men and women changed over time. In 1900, women made up 40 percent of the Lebanese immigrant community in the Northeast, West, and Midwest. But in the South, women made up only 35 percent of the immigrant population. While we do not know for certain the reasons behind this difference, we speculate that it is partly due to the fact that Lebanese immigration to the South came later than other areas, with fewer families settling overall in the region.

By 1910, the South caught up to the West and Midwest (still with a 60 percent to 40 percent ratio), but in the Northeast the ratio of women grew to 43 percent. The Northeast still boasted the highest male/female ratio in 1920, but across the board, all regions saw a closing gap between men and women with an average split of men at 57% and women at 43% of the population.

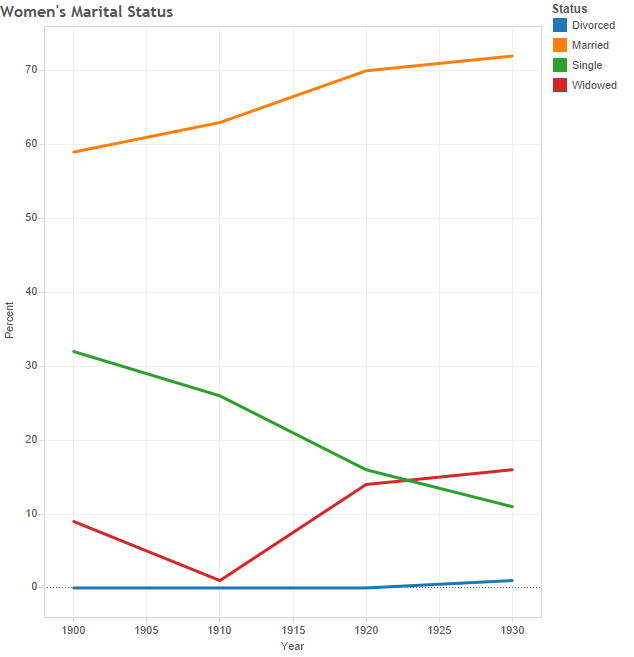

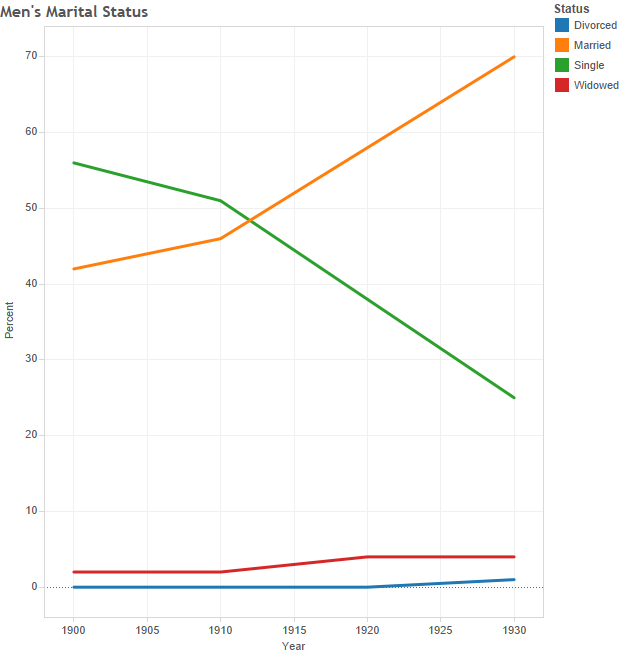

Were Lebanese immigrant men more likely to be single and women more likely to be married?

Answer: Yes.

In 1900 and 1910, the majority of Lebanese immigrant men were single (56 and 51 percent respectively), while the majority of women were married (59 and 63 percent). However, by 1920, more Lebanese men were married than single (but still fewer than the percentage of women who were married) and by 1930 the same percent of each population (about 70 percent) was married. The decrease in the number of unmarried men and women between 1900 and 1930 reflects the evolution of the community from its early transient nature (in terms of intents to return to Lebanon, as well as

the type of work practiced) to a more settled community in later years.

How many Lebanese married outside their ethnicity?

Answer: About 8%.

Using our census data we cannot necessarily tell how many marriages were exogamous (marriage outside a social group); however, we can track the number of children born to exogamous and endogamous marriages. In 1900, 95 percent of children born to Lebanese immigrants had two Lebanese parents. One percent had an American father and Lebanese mother and four percent had a Lebanese father and American mother. In 1910 and 1920, this shifted so that seven percent had a Lebanese father and American mother, one percent had a Lebanese mother and American father, and 92 percent had two Lebanese parents. By 1930, only 85 percent had two parents born in Lebanon but this large drop might be explained by the coming of age and marriage of Lebanese-Americans born in the US.

According to historian Linda Jacobs, “if a Syrian married outside the community once, he usually did it a second time as well.” [1] Gabriel Abukalil (or Kalil) is one such example. Immigrating in 1893, Gabriel peddled goods and worked in a restaurant with his brother Alexander. At the age of 29 in 1899, Gabriel married Margaretta Johnson, a very wealthy 75 year old American from Buffalo, New York. With her money, Gabriel and his brother were able to open their own restaurant in New York City; however, after two years, Margaretta claimed Gabriel had abandoned her and absconded with her money. Their marriage was annulled in 1907. Shortly after, Gabriel married Mary Brossman, an American of German descent from Philadelphia. There, Gabriel opened another restaurant and he and Mary had a son in 1909. Sadly, in 1920, Mary had been committed to an insane asylum where she died years later in 1944.

Conclusion

Examining gender in the US Census from 1900 to 1930 has allowed us to juxtapose fact with common assumptions and myths about Lebanese immigration to the US. Far from accepted tale

that men left Lebanon seeking fortune to improve the lives of their families at home, or to establish the foundations of families in the US, the census shows that women were a part of this journey from the start. The Khayrallah Center will use this cursory analysis to inspire further study into factors that drove immigrant women’s agency in early Lebanese-American communities.

Sources

[1] Jacobs, Linda K. Strangers in the West: The Syrian Colony of New York City, 1880-1900. New York, Kalimah Press, 2015.

- Categories: